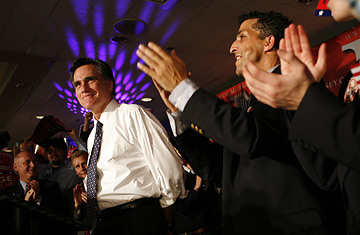

Former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney celebrates his win in the Michigan Republican primary.

The Mitt Romney who gave his acceptance speech at the Embassy Suites in Southfield, Mich. — an upscale Detroit suburb — had a hair out of place. Maybe more than one. He was in his shirtsleeves. He was, as a spokesman said, "the stripped-down, acoustic Romney — Romney unplugged." The clunky chimera candidate who tried so hard to prove his conservative credentials had become a model of simplicity with one major theme: He was a successful "can-do CEO," in the words of state G.O.P. chairman Saul Anuzis, "who knows how to get jobs back."

Aides point to this pared-down platform as proof that the Mitt that won Michigan "is the Mitt he introduced himself as," Anuzis explains. "He got away from tailoring his message to different constituencies." Not unlike the storyline Hillary Clinton latched on to after her comeback win in New Hampshire, Romney did seem to find his true voice in his home state. There is no denying that he came across as more energized and focused than earlier in the campaign. Spokesman Kevin Madden asserts that the governor won because the former consultant finally shed himself of consultants: "There were no shortage of unsolicited advisors. Everyone had an opinion about what he should be doing."

Still, Romney's success here is a tacit repudiation of the candidate that ran in Iowa and New Hampshire, and could spur the same doubts about him that have dogged his campaign since it began. After all, if he finally won in Michigan because he was being real, then he wasn't being real before, right? And if he's not carefully tailoring his messages any longer, why was his campaign so beautifully suited to the state of Michigan? "His detractors say he ran for the governor of Michigan," says Neil Newhouse, Romney's pollster from his Massachusetts races.

Indeed, the very things that helped Romney handily defeat McCain by almost ten percentage points — his more optimistic view of the economic future and claims that the auto industry's jobs could be saved — could look to some voters like the worst kind of political pandering; in other words, the same old Mitt.

Romney's camp, of course, sees it very differently. "It was a perfect storm in Michigan," says Anuzis. "There's a potential national recession, and Mitt comes in and starts talking about turning things around. National issues coincided with state issues. "The campaign has seized upon this equivalence between Michigan's problems and the nation's to explain away his losses in New Hampshire and Iowa. "Michigan is a microcosm of America," says Madden, implying that the earlier, and more influential, states shop for boutique candidates. Apparently South Carolina falls into that category as well, since Romney will likely bypass Saturday's primary in order to dominate the little-noticed Nevada Republican caucus.

Moving on to Nevada, however, is less about national appeal than it is about the campaign's new rationale for an eventual nomination: Racking up total votes and total delegates and appealing to the squinty insiders who game out primary voters like, well, bookies. Boasting of delegate count does not generally create a feeling of success in average voters, but, according to Anuzis, "that delegate stuff appeals to activists," who will vote more "pragmatically" on "the winnability aspect." Whether Romney can afford to pay less attention to a traditionally crucial G.O.P. state like South Carolina remains to be seen. Mark Salter, a McCain senior adviser, doesn't think so: "If you're gonna claim the mantle of the latest front-runner, you've gotta compete."

But a long-term focus on activists and hard-core Republicans makes sense in a nominating race that could define the future of the party, and could cost lots and lots of money in the process. The self-funded Romney's frequent invocations of Reagan are a sharp contrast to McCain's focus on national security, and Huckabee's churchy charm. All three front-runners are appealing to different strains of traditional Republican values; there's the Wal-Mart Republican (Huckabee), the establishment Republican (Romney), and the independent Republican (McCain). After Michigan, all three appear to have an equally good shot at the nomination. But for voters to have faith in the man who won Michigan, Romney can't afford to change his tune.