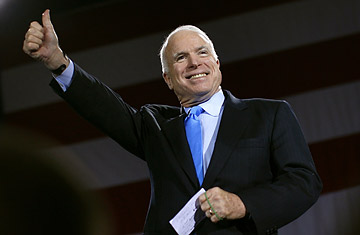

Republican presidential candidate U.S. Senator John McCaingives a thumbs-up during a rally at Pontiac-Oakland County International Airport in Waterford, Michigan, January 9, 2008.

John McCain did not celebrate when AP called New Hampshire in his favor Tuesday night. His supporters, downstairs in the hotel ballroom of the Nashua, N.H., Crowne Plaza, erupted in cheers. But upstairs, in the Presidential Suite, McCain and half a dozen others, including his wife, Cindy, continued to watch Fox News. Faces were tense; Cindy crossed her arms and held her elbows like she was keeping herself physically together.

Then Fox called it. There was less of a scream than a sigh of relief. Now it was almost possible to believe it was true. Maybe.

Much has changed for John McCain since his underdog victory here over George W. Bush in 2000. For one thing, his victory here was much more unlikely than his victory back then. To come from behind is one thing. But to be the presumed front-runner, then fall to obscurity, then come from behind...that is Lazarus.

At the same time, he faces massive new challenges. He has become the face of an unpopular war — and an unpopular stance on immigration. Then there is his age. Should his victory carry him to the finish line, he would be the oldest man ever elected to a first term as President.

But something else has changed as well, and it's his knowledge of just how precarious a New Hampshire victory can be. His advisors have already put up an ad in Michigan, whose primary falls on Jan. 15. The 30-second spot called "Reform," encapsulates the message they believe helped them win New Hampshire: McCain faces the camera and tells viewers how angry he's made "big spenders," "special interests" and "defense contractors."

What McCain has going for him in Michigan, adviser Steve Schmidt argues, are his opponents. "In the American economy, there are only two truly perishable commodities," says Schmidt, "U.S. currency and time." The six-day spread between today and the Michigan primary will make it difficult for Romney to overcome the impression that he has lost not just momentum, but any chance to beat the eventual Democratic nominee.

Perhaps even more important for McCain in Michigan is the decision of Huckabee to compete there. Michigan has a substantial evangelical population, one that Romney has courted assiduously. Huckabee's appeal to that base may take votes directly out of Romney's column.

And McCain's other advantage is that he isn't broke anymore.

"We're fully funded in Michigan and South Carolina," says Charlie Black, a former Bush advisor who stayed with McCain after his summertime implosion. The campaign has raised enough money over the past few weeks that no one is worried about being able to continue on through Florida's primary on Jan. 29. "Starting tomorrow, every dollar we raise now will go to Florida."

But it's worth remembering that the arguments of consultants have a half-life shorter than a gnat in this race. McCain's campaign in New Hampshire is itself evidence of the unpredictability of this election. (Romney outspent McCain by a margin of at least four to one here, for one thing.) In the hours before results started to come in, top McCain aides were still unsure if they would even win.

As for McCain himself, he wisely does not try to explain his victory in linear narratives. The morning of the primary, wearing the same green sweater and staying in the same room as in 2000, he explained his own strategy for the day: "There is no superstition I won't indulge," he said. "I believe in luck."