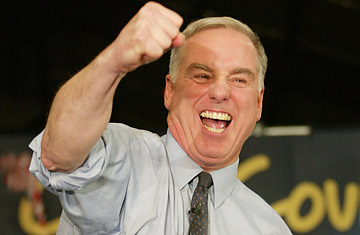

A defiant Democratic presidential candidate Howard Dean addresses supporters following his third-place finish in the Iowa caucuses January 19, 2004 in West Des Moines, Iowa.

There'll be only two winners on caucus night — but nobody can afford to sound like a loser. After months, and in some cases years, of begging Iowans for their support, the candidates will finally get some real results tonight. And what they say about the outcome can define or derail the rest of their campaign.

For speechwriters, there are three stock rhetorical approaches: declare victory (even if you didn't win); declare viability (and the desire to fight another day), or decide that the results didn't matter (and that the cause continues).

Victory is easy. You thank everyone. You beam. You kiss your spouse and ride the goddess momentum all the way to New Hampshire. But what happens if you didnt actually win? If possible, you declare victory anyway. The most famous example of the "declare victory" strategy was Bill Clinton in the 1992 New Hampshire primary. Many forget that Paul Tsongas — the lethargic, fiscal conservative from Massachusetts — actually won the '92 New Hampshire primary by 9 percentage points. But it was Bill Clinton who after staring down the media over an alleged affair with Gennifer Flowers and questions about his draft status during Vietnam turned a second-place finish into a triumph. "Tonight, New Hampshire's made me the Comeback Kid ... I've proven one thing: I can take a punch." Those two sentences defined the rest of the race — and arguably, Clinton's presidency.

Not everyone can be the Comeback Kid. For a campaign that pulls up lame, but isn't ready to be euthanized, viability is the play. For some, this means a creative interpretation of the results, such as Senator Joe Lieberman declaring after the 2004 New Hampshire primary that his fifth place finish was, in actuality, "a three-way tie for third place." But there's danger in the viability strategy, danger exemplified by Howard Dean. After finishing a disappointing third in '04, Dean declared: "We're going to South Carolina and Oklahoma and Arizona and North Dakota and New Mexico. We're going to California and Texas and New York, and we're going to South Dakota and Oregon and Washington and Michigan. And then we're going to Washington, D.C., to take back the White House." Then, Dean let out the yawp heard round the world, branding his remarks forever as the "I have a scream" speech. The lesson? Don't oversell sell the viability thing.

For candidates who have just gotten shellacked, the best strategy is a declaration that the results didn't matter because of the peculiarities of the specific contest. George W. Bush mastered this in 2000. After he lost the New Hampshire primary by 18 percentage points to Senator John McCain, he downplayed the significance of one victory: "The road to the Republican nomination and the White House is a long road. Mine will go through all 50 states." Then he argued that McCain, "spent more time in this great state than any of the other candidates, and it paid off" — the rhetorical equivalent of, "I wasn't really trying anyway."

The polls are too tight right now to predict who will win Iowa. But be sure that come tomorrow night, all three speeches will be written. And how they're delivered may tell the tale come New Hampshire.

Kenneth Baer is the founder of Baer Communications, LLC. Jeff Nussbaum is a principal of the communications firm West Wing Writers. Both were speechwriters for Vice President Al Gore.