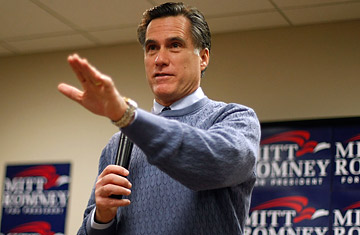

Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney speaks in Columbus Junction, Iowa.

On New Year's Day, two days before the Iowa caucuses, Mitt Romney crisscrossed eastern Iowa in his red, white and blue Mittmobile, trying to inch past the insurgent Mike Huckabee in the final moments before the first presidential nominating contest in the nation. He touched down at seven different house parties, or, as the day's inescapable football metaphor would have it, "House Party Huddles." Of course, they were less huddles than tailgate parties with large-screen TVs instead of stadiums and living rooms instead of parking lots. And Romney was less a featured attraction than halftime entertainment. In Clive, Iowa, his visit coincided with the third quarter of the Michigan game; as he spoke, guests in the downstairs rec room discreetly whispered the score to guests on the stairs.

Those gathered treated the former Massachusetts governor with respect and somewhat distracted enthusiasm. Romney marched through each event with studied conviviality. After an abbreviated stump speech, he would walk gingerly through the crowd, stopping to comment when someone was decked out in conspicuous sports gear. In Johnston, he patted the shoulder of a man in a University of Missouri jersey and asked, "Oh, are you a 'grad'? I mean, a graduate?"

This is not a candidate who wants to leave anything to chance, even the interpretation of words that the Governor manages to bracket with unneeded quotation marks. ("'Small varmints,' if you will.") One would be forgiven for not believing the governor when he said, as he did at each stop, "Elections can be fun things."

When Romney attempts to communicate that he is having fun, or really experiencing any emotions at all, he lapses into awkward anachronisms: John Edwards' evocation of two Americas "just 'frosts' me." Or, recounting his reaction when his son had named his grandson after him: "I just could not have been more pleased!"

But the people interested in caucusing for Romney aren't necessarily thinking about fun. Romney has run an unapologetically analytical, boldly flavorless campaign. "He's been extraordinarily successful using the same approach his entire life, and that's the way he's run his campaign," says unaligned Republican pollster Whit Ayers. "You gather the data, ask the questions and make the best rational choice you possibly can." Romney is betting that Iowa voters will approach their decisions on whom to vote for in the exact same way he has approached his campaign.

At the house parties, there are signs that his cool competence may help carry him past the surging Huckabee. When, taking a break from Bowl games, partygoers tick off their reasons for supporting him, it is a shopping list, not an argument: "He'll secure the border, fight terrorism and protect family values," says a woman in a fuzzy purple sweater in Ankley. In general, they do not talk about how they feel about Romney at all. There is none of the teeny-bopper swooning that erupts in Obama's wake, or the easy laughter Huckabee can summon with a drawling punchline. Instead, there are spreadsheets. "When you look at them morally," says Eric Carlson, a 401(k) manager in Des Moines who is deciding between Romney and Huckabee, "they're about equal. So it really comes down to management."

The negative ads and verbal barbs flying between the Huckabee and Romney campaigns do not seem to come much into play in these sedately decorated suburban homes. His supporters seem unconcerned about Romney's flip-flops; in Clive, a neighbor of the hosts says of Romney's earlier pro-choice views, "Well, that's not what he believes now." But they are just as dismissive of Romney's charge that Huckabee has a "liberal" approach to government. Huckabee "is a good man," says Carlson. "He's got his heart in the right place."

Indeed, the contest between Romney and Huckabee has been widely framed as a contest between Iowans' body parts: head (Romney) versus heart (Huckabee). Will most of the people who show up on caucus night be "heart" people — the loosely organized homeschoolers and evangelicals to whom Huckabee owes his front-runner status? Or will they be "head" people, precisely targeted and courted by the Romney campaign? (Staffers boast of having made over 36,000 phone calls to supporters in the past two days.)

Most conservative Iowans may not fall completely in either camp. "There are probably some people who are bifurcated easily," says Ayers — they are either head people or heart people — "and there are a whole bunch of people who are torn between the both." Ayers admits, "I can look at the two appeals [of Romney and Huckabeee] and find something appealing in both. Frankly, I don't know how I'd sort it out and I do this for a living."

After the cautious sociability of the house parties — which are tailored to those who may not have made up their minds — the tarmac rallies Romney held on Wednesday were downright raucous. Crowds only numbered between 50 to 100, not much larger than a house party, but they were enthusiastic. There were whistles, screams and signs whose wordy perfectionism — one lists all seven of the planks of Romney's stump speech — contrast sharply with the brightly-colored faux folkiness of the signs distributed by volunteers. These are people who have fallen for the guy they entered into an arranged marriage with. "I love him! I love him! I love him!" shouts a former teacher in Cedar Rapids.

Yet Romney's best chance to succeed on Thursday depends less on turning out the analytical voters than in figuring out what tumblers clicked to link the heads and hearts of those at his rallies. He may already have done so. Since Huckabee's article in Foreign Affairs, in which he criticized Bush for an "arrogant bunker mentality," Romney's speeches have been peppered with careful defenses of the current Administration. He says he doesn't know "if the Governor was joking" in the article, "but now isn't the time to mock our President." Even as he offers slightly limp critiques of the initial strategy in the war in Iraq, he plucks up Bush's mantle from the mud and declares, "He has kept us safe for six years. We ought to be grateful to him."

Bush is, most emphatically, not a "head" guy. "But it's a head decision to hew close to his legacy," says Ayers. "All you have to do is look at the approval rating of the President among Iowa Republicans" — it stands at a remarkably high 64% — "and, well, an analyst looking at how to climb back into first could make that decision pretty quick."