Republican candidate for President John McCain is trying to regain the lost momentum in his campaign.

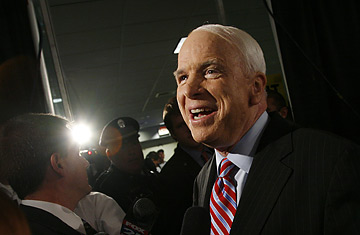

Senator John McCain arrives in Portsmouth, N.H., Wednesday night to begin the second leg of what he has dubbed his "No Surrender Tour," a traveling Iraq war and campaign pep rally engineered to coincide with the congressional testimony of Gen. David Petraeus and its attendant media frenzy. Given the public's continuing frustration with the war and McCain's significant stumbles earlier this year, the presidential candidate's counterintuitive approach may seem like a risky strategy, but it now has staffers talking "comeback." A recent uptick in national polls and a strong performance in last week's New Hampshire debate has the campaign hopeful that the Senator's decision to, as an internal memo framed it, "own the surge" will reinvigorate McCain's chances among the Granite State's notoriously skeptical voters.

McCain own surge in the polls is admittedly modest: he's gone up six points in the CBS/New York Times poll, four in USA Today's, and just two in a survey by the Washington Post and ABC. Those results predate Petraeus' Capitol Hill performance, but they do coincide with start of McCain's tour, and with his testy rebuttal to Mitt Romney's assertion during the most recent G.O.P. debate that the surge is "apparently working": "The surge is working, sir, no, not apparently," McCain scolded. "It's working."

After the campaign imploded in the spring, with McCain's coffers all but dry and his bloated operation scaled back, the remaining staffers had always hoped to "rebuild Fort New Hampshire," the site of McCain's upset triumph in the 2000 primaries. They just didn't suspect the structure's foundations would be something as shaky as the war. Until recently, the thinking was, as one adviser put it, "what immigration is for McCain in Iowa, the war is for him in New Hampshire." Which is to say, it was killing him. And just as McCain would often bring up his immigration reform proposal in Iowa town halls whether someone asked about it or not, the candidate was equally irrepressible — even glib — about bringing up the war unprompted in New Hampshire. ("Thanks for the question, you little jerk," McCain told a student a Concord high school student who asked about his age last week. "You're drafted.")

But campaign advisers say New Englanders are starting to respond to McCain's steadfastness on Iraq, even if they don't agree with his policies. They point to the focus group of New Hampshire Republicans assembled by Frank Luntz to watch last week's debate; McCain's numbers spiked the highest when he told the audience that he empathized with their "frustration" and "anger" over the situation in Iraq, and that he wants to bring the troops home as well: "But I want them home for the right reasons. I want our troops home with honor, otherwise we will face catastrophe and genocide in the region."

Voters' willingness to see past their differences with McCain on the war may also have to do with McCain's carefully calibrated moves to distinguish between his support for the war and his support — or lack of it — for the Bush Administration. He's long emphasized, as he made a point of doing during the Petraeus hearing, that he was one of primary critics of the Administration's handling of Iraq. But when he emphasized it as a point of distinction just prior to the New Hampshire debate — saying that his skepticism about Bush's strategy predated that of even the Democratic candidates — the message finally resonated, says senior aide Mark Salter.

Of course, it's easy easy to speculate about McCain's surge now, but assessing his improvement on the ground is as difficult to do as in Iraq. The most recent New Hampshire poll, conducted by the Los Angeles Times and Bloomberg, shows McCain in third place at 12%, far behind front-runners Rudy Giuliani and Mitt Romney and just barely ahead of Fred Thompson. And McCain's ability to sell his stance on the war as a principled stand may not matter if he doesn't have enough money to get his message across. "He may get good press, but he has no resources," says Larry J. Sabato, director of the University of Virginia's Center for Politics.

Other supporters of the surge point to the same distinction as key to McCain's chances. "This is not about Bush," says Pete Hegseth of Veterans for Freedom, a group that advocates continuing in Iraq. "This is about success, and McCain realizes that. I don't think his calculation is: 'Am I in step with the Administration?' That he happens to be in agreement with the Administration doesn't bother him one bit." It may, however, still bother a lot of voters, and they will decide whether McCain can sustain his surge, much less pull off a victory.