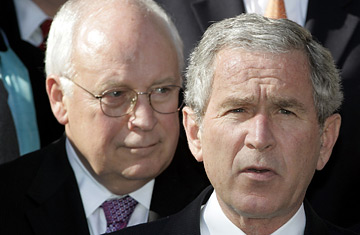

Vice President Dick Cheney and President Bush

President George W. Bush's failed attempt to pass comprehensive immigration reform may prove he's not much of a consensus builder on Capitol Hill, but when it comes to playing rough with Congress, he clearly knows what he's doing. Bush stiff-armed the House and Senate judiciary committees Thursday, dispatching his lawyer to assert executive privilege and tell them he won't comply with their subpoenas for documents in the case of the fired U.S. attorneys. Backed by letters from the Justice Department's top lawyers, Bush effectively told Congress to go to hell.

There's nothing new there. Even when Republicans were in control on Capitol Hill, Bush's hallmark was a jaunty disregard for the legislative branch. And he's hardly the first President to claim the privilege: Clinton successfully asserted executive privilege several times, as did George H. W. Bush and many others before them. But a senior administration official speaking to reporters today said Bush is prepared to go a step further, instructing two former members of his staff now outside government not to comply with subpoenas to testify either.

Bush's lawyers were asked on the conference call with reporters for examples of other presidents using executive privilege to keep people who were not current employees of the executive branch from testifying before Congress and couldn't immediately come up with one. Eventually they pointed to a case from the 1950s when President Dwight D. Eisenhower exempted former President Harry Truman from complying with a Congressional subpoena.

The Democratic Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Patrick Leahy of Vermont, said Bush was engaging in "Nixonian stonewalling" but there's a method to the White House's approach. Legally, Bush may be stretching executive privilege by claiming it allows him to prevent private citizens from responding to a Congressional subpoena, but politically he's just playing hardball.

"The White House is taking a strong stand on this to convince the Senate that they are deadly serious about protecting private conversations between the President and his staff," says Ken Duberstein, who was Reagan's chief of staff in his second term.

With executive privilege as ill-defined as it is, much of the battle between Congress and the White House is a protracted negotiation. Bush's move ups the bidding: the Democrats thought they'd set up a fight over administration documents and now they've got a fight over testimony by former members of the administration, too. And even though Bush might lose the testimony battle if it ever gets to court, by then the end of his term will be in sight.

This is the second time the administration seems to have outmaneuvered Congress over the U.S. Attorneys' investigation. The previous play was to offer off-the-record conversations between top aides, including Karl Rove, and the Congressional committees, but only without a transcript — a stance Bush's lawyer reasserted Thursday. That was an offer the Democrats couldn't accept, but it let the administration claim it was negotiating in good faith, and it bought Bush several months.

Bush's hardball play with Congress does have one potential downside. For now, most Americans aren't paying close attention to his battle with Congress over the U.S. attorneys. But if they do, and it starts to drive his numbers below their already record lows, pressure could mount on Bush to defuse the conflict. At a certain point, 2008 candidates on the Hill and the presidential campaign trail will start looking at the president less as a lame duck and more like an albatross.