We were supposed to speak up but no one could figure out how to use the microphones. After a flurry of typed responses and awkward silences, Professor Lorraine Leavitt, who has taught online courses at San Diego-based National for seven years, filled the dead air time with a discussion of how hard it can be to produce great teachers from an online course.

At least, I think she did. As she spoke, the echo in the chat system became so loud that I missed most of her speech.

"It's kind of like the Wild West," Leavitt, who worked in California's public schools for 32 years and has taught in-person teacher training courses, said in an interview after the course ended. "We're at the beginning of online instruction."

At a time when brick-and-mortar teacher training programs are under fire, the burgeoning world of online teacher training has the potential to help or hamper efforts to improve public education. Internet classes could widen access to the profession and be a solution to teacher shortages. But if online training programs can't ensure quality, they'll instead just pump thousands of ill-prepared teachers into the system.

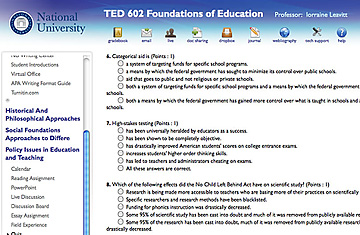

For four weeks last fall, I joined 19 teacher-hopefuls in a virtual course at National University to explore how well the rapidly growing field is preparing individuals for the classroom. My "Foundations of Education" class was a required course in the master's program for teachers-to-be, covering subjects like standardized testing, teaching in multicultural classrooms and the history of public schools in America.

I learned a lot about education but little about how to conduct myself in a classroom. That was partly because this class, as an introductory course, didn't cover specific teaching strategies. But some skeptics question whether the basic lack of human interaction during an online class, regardless of the subject matter, can lead to problems down the road.

When teachers trained online enter the classroom for student teaching, Leavitt said, sometimes "we see problems we maybe could have helped earlier," such as the way a teacher answers student questions. "What it says to me is we really have to start earlier in designing our online classes to be much more interactive."

In other words, even the earliest and most fundamental online teacher-training classes must be interactive so students can learn from the instructor—and each other—how to present information and the instructor can start giving tips as early as possible.

Online courses are exploding across the country at every level of education, and teacher training is no exception, fueled by teachers seeking master's degrees as well as career switchers looking for a convenient way into a new field.

The top six degree-granting institutions for bachelor's and master's in education in 2010 were entirely or partly online private programs, according to the U.S. Department of Education, with for-profits University of Phoenix and Walden University leading the list. Combined, the two awarded more than 14,600 education degrees. Nationally, 309,685 education degrees were given out in 2010.

National University, a private, nonprofit university based in San Diego that has both in-person and online programs, is the nation's eighth largest producer of education degrees, awarding more than 2,000 in 2010. Ten percent of California's teachers earned their credential from National, including at least three former state Teachers of the Year, according to the university.

In curriculum and content, online teacher training programs are similar to traditional programs and require a comparable number of hours that candidates spend doing their student teaching requirement in brick-and-mortar classrooms. The online instruction offers inherent strengths—it's impossible, for instance, to evade class discussions, meaning professors can more closely monitor written participation—and at least one glaring weakness: There are limited opportunities for in-person interactions.

"I am nervous about an enterprise that's training people to be face-to-face classroom instructors that's entirely online," said David Figlio, a professor of education and social policy at Northwestern University who has done research comparing student performance in online and in-person lecture classes. "It's hard to think of too many jobs that have more requirements for genuine, old-fashioned face-to-face contact than teaching."