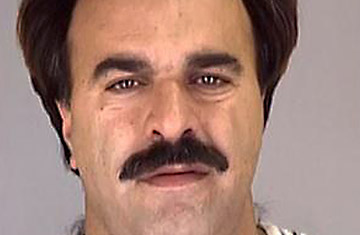

Manssor Arbabsiar, an Iranian-American used-car salesman, is accused of conspiring with Iran to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the U.S.

(2 of 2)

Manhattan's U.S. attorney has been making the case that narcoterrorism poses a unique danger to the U.S. since 2007. Working with the Drug Enforcement Administration's (DEA) multiagency Special Operations Division — and empowered by a new, vastly broadened view of American jurisdiction — federal prosecutors have built an impressive roster of sting cases that have netted suspects all over the world, from Liberia and Romania to Togo and Honduras; among these is Viktor Bout, the alleged arms merchant nicknamed the Lord of War, whose trial in New York City began on Thursday.

The Bout case has endured controversy from the outset. After his 2008 arrest in Bangkok, American and Russian officials fought through Thai courts for custody of the accused arms dealer. Following his extradition to New York, the federal judge overseeing his case initially found that the DEA Special Operations Division agents who arrested and interrogated Bout "were not credible" in certain instances and had made "false" representations to Bout. (For reasons that are not yet clear, the judge, Shira A. Scheindlin, later rewrote her filing, removing the language that directly accused the DEA agents.)

Like the Arbabsiar allegations, many of the other cases pursued by the DEA in the Southern District of New York reverberate through diplomatic and national-security circles. In one case, accused Afghan drug lord Haji Juma Khan was charged with aiding the Taliban and was taken to lower Manhattan to face charges. In pretrial motions, the federal government successfully invoked state secrets and national-security privilege concerning the evidence. (Nearly three years have passed, and Khan has yet to face trial.) A case announced this summer involves an Iranian, Siavosh Henareh, accused in a drugs-for-weapons deal implicating Hizballah in Lebanon.

Sabrina Shroff, the federal public defender representing Arbabsiar, sees his indictment within this legal continuum. "There seems to be a thread running through these cases — from Haji Juma Khan to Viktor Bout to Siavosh Henareh to this case. Whether the thread is the [Special Operations Division] or the now routine international stings or another thread, that is only visible to law enforcement," says Shroff. "It is a dangerous one that ensnares and uses individuals without regard for their rights under our Constitution."

The Arbabsiar case stands out from the others in its category. Unlike in nearly every other narcoterrorism sting pursued, the DEA almost immediately handed over its informant to the FBI, limiting its role in the investigation. The crimes attributed to Arbabsiar in the indictment appear to have been initiated by the accused in the U.S. — in this case, Texas, a state at the center of a political battleground on the issue of border security. Still, like most of the other cases, the ultimate question is likely to hinge on the credibility of the party that turned Arbabsiar in. A former DEA agent, Mike Levine, who now serves as a covert-investigations instructor and expert witness on law-enforcement procedures in criminal and civil trials, says the evidence as presented in the Arbabsiar indictment "doesn't seem logical" and warned that an outlier to the case is the Mexican narcotrafficker informant. "Agents want the informant to be successful because they want the case to be successful," Levine says. "A common flaw of investigators is agents looking the other direction of any information that will make their informant look bad." He notes a strange aspect of the case: "DEA, of all agencies, are best at handling informants, yet DEA gave the informant over to the custody of the FBI." But this case was strange from the moment it was made public.