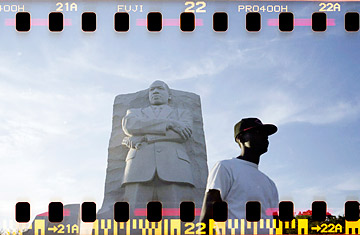

A visitor to the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington on Aug. 22, 2011

A year ago, as my interview wrapped with President Obama in the Oval Office, he led me to the bust of Martin Luther King Jr. by Harlem Renaissance sculptor Charles Alston that he had installed near a bust of Abraham Lincoln. Obama's gaunt visage creased in delight as we gazed in silent awe on the face of a man the two of us baby boomers have acknowledged as a great inspiration. In the near future Obama will participate in a far more public recognition of the martyr's meaning when he speaks at the dedication of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall. King becomes the first individual African American to occupy the sacred civic space dominated by beloved Presidents like George Washington and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. King's image on the Mall is a sturdy reminder that his story, and the story of the people for whom he died, helped to rescue American democracy and make justice a living creed. King's memorial is even more impressive because his statue rises 30 ft. high on a direct line between the likenesses of Jefferson and Lincoln, dwarfing those memorials by 11 ft. — it is one of the tallest on the Mall. Even in death, King is still breaking barriers.

Obama's words on the Mall will be framed by a bitter dispute over King's legacy in black America and its revelation, or distortion, in leaders like Al Sharpton and Obama himself. Sharpton has emerged as an improbable leader of black America and a more improbable defender of Obama, a status that challenges his prophetic credentials in some quarters. Sharpton tangled on radio in 2010 with television host Tavis Smiley over Sharpton's contention that Obama shouldn't "ballyhoo 'a black agenda.' " Earlier this year on cable television, Princeton professor Cornel West shouted at Sharpton that the voluble minister could be "easily manipulated by ... the White House" to become the "public face" of entrenched Wall Street and corporate interests.

If Smiley and West fear that Sharpton has become Obama's pal and not his prophet, they seek to take up the slack and press Obama about his neglect of blacks and the poor at every chance. Their relentless criticism has earned them rebukes from many black folk and the enmity of radio host Tom Joyner, who once championed the duo, while Joyner's colleague Steve Harvey derided the pair as "Uncle Toms." These vicious attacks didn't stop Smiley and West from hitting the road recently for a 16-city "poverty tour" to spotlight the invisible poor in the name of King. Unfortunately, the political and racial circumstances that gripped their crusade drew more press to them than to the poor. Obama, Smiley and West and Sharpton all claim King's example. Who makes the most of it is a complicated story.

It is both fitting and ironic that Obama presides over the cementing of King's status as an icon in the national political memory. Obama's historic presidency is unthinkable without King's assassination and the black masses' bloodstained resistance to racial terror. Obama embraced King's rhetoric of justice during his presidential campaign while eschewing his role as prophet. Presidents uphold the country; prophets often hold up an unflattering mirror to the nation. King may now be widely regarded as a saint of American equality, but he often had to criticize his nation's politics and social habits to inspire and, at times, to force reform. He helped to make America better by making it bend to its ideals when it got off course as its loving but unyielding prophet. Had he lived, King would have certainly hailed Obama's historic feat even as he took issue with some of the President's policies toward black and poor people. It would have been principled criticism rooted in an obsession with improving the lives of the vulnerable. To paraphrase Obama's favorite film, The Godfather, King's arguments would have been business, not personal.

The same doesn't appear to be true for Smiley and West. Smiley openly criticized candidate Obama for not attending his State of the Black Union gathering in 2008, and many believe the slight stuck in Smiley's craw and has led him to blast the President ever since. The notion is swatted away by Obama's appearance on videotape at Smiley's 2009 event. Smiley criticized Presidents Clinton and Bush too, though, it must be noted, not as visibly or vocally as he's done with Obama. Smiley has admitted that Clinton seems to him like a fourth brother, a closeness that may have tempered his criticism of the former President. No such restraints keep the media marvel from an intrepid criticism of Obama.

The same is true for West, a brilliant intellectual who has even more aggressively aired his grievances, calling Obama "a black mascot of Wall Street oligarchs and a black puppet of corporate plutocrats." It proved a pattern: West's trenchant analysis of Obama's policies is often sullied by needless name-calling. West's gripes are sometimes disturbingly personal and laced with macho psychoanalysis and peals of wounded ego: disgust with Obama because West and his family couldn't get Inauguration tickets (West's complaint that the bellman who carried his bags at a Washington hotel could get a ticket when he couldn't undercuts his noble advocacy for working and poor folk); the perception that Obama was afraid of a "free black man" like West (a belief that may be unfounded in light of Obama's in-your-face dressing-down of West after a presidential address in Washington); and the hostility West unleashed when he said that he wanted to "slap [the president] on the side of his head" after Obama had ambushed and embarrassed him in their D.C. spat. West's loving heart may belong to King at his best, but his lashing tongue belongs to Malcolm X at his worst. His legitimate criticism is lost in the mix.

Sharpton's evolution may put him closer to King the presidential dealmaker than critics of the supremely gifted leader and newly minted talk-show host have so far let on. Sharpton cut his prophetic teeth on urban protest as an unpolished version of his idol Jesse Jackson, courting controversy and combatting police brutality against poor and working-class blacks. The accoutrements of his guerrilla resistance included the jogging suit, the lavishly styled perm, the bullhorn and the shrilly amplified mantra "No justice, no peace." Sharpton's odyssey from stubborn outsider to ultimate insider is documented in the shift to well-tailored suits and a more modest coif. Sharpton scaled the ire of the white masses and the embarrassment of the black elite to become a savvy power broker with unparalleled access to Obama. It remains to be seen what Sharpton makes of his opportunity, but the fact that he has it doesn't mean he should be condemned as a sellout. In fact, his greatest contribution may be not what he makes happen but what he keeps from happening by being at Obama's ear or elbow.

Constructive criticism of Obama is healthy; demanding that he pay attention to the needs of poor folk and people of color is righteous. Confusing personal beef with principled criticism only ends up undermining the high aims of social prophecy. When critics call Obama names, they sound no better than the bigots who wish him failure and death. We ought to remember that as we celebrate a man who was a selfless prophet and soldier of truth before he was murdered and turned into a saint and statue.

Michael Eric Dyson, a Georgetown professor and contributing editor of TIME, is author of April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King Jr.'s Death and How It Changed America. Follow him at @MichaelEDyson.