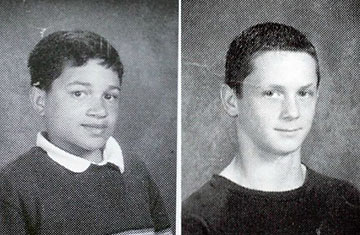

Lawrence King, 15, left, was fatally wounded while seated in a classroom at E.O. Green Middle School in Oxnard in 2008. Brandon McInerney, right, is on trial for the killing. He was 14 at the time of the shooting.

Emotions have run high since the very first day of Brandon McInerney's trial for murder. Perhaps that's because the killing of his gay middle-school classmate Lawrence King was as emotionally jarring as it was appalling. When McInerney, then 14 years old, shot 15-year-old King twice in the back of the head in a school computer lab three years ago, the incident jolted the coastal city of Oxnard, California, thrust two unstable households into the spotlight, and made King a rallying point for the gay community across the nation. The shooting exposed a multitude of sensitive subjects all at once: issues regarding gays, transgender people, bullying, white supremacy, child abuse and school violence came to the surface.

And there were other kinds of baggage. Before proceedings had even begun, almost two months ago, the judge reportedly barred McInerney's brother from watching the proceedings after he spoke to members of the jury. Since then, former classmates have broken down crying on the witness stand. McInerney's mother and a teacher cried when the defense displayed a picture of King holding a homecoming dress and smiling, prompting the victim's father to storm out of the courtroom in disgust. The defense has even tried to disqualify the judge, alleging he was biased in favor of the prosecution.

In theory, the jury should only be concerned with the facts. But what happens when emotion becomes a fact, one that could benefit the defendant? The question at hand is whether McInerney, who is being tried as an adult, committed a hate crime as well as murder with premeditation, as the prosecution is arguing, or whether he committed manslaughter in the heat of extreme emotion — a crime of passion — as the defense argues. A first-degree murder conviction would get McInerney 53 years to life in prison, while manslaughter would reduce the sentence to as few as 18 years, according to the defense attorney. (No one is debating whether McInerney shot King; an entire classroom saw him do it.)

Prosecutor Maeve Fox is arguing that there was clear premeditation. According to testimony, after King made sexual advances, McInerney told another student he was going to bring a gun to school, went home, spent the night, brought a gun the next morning, sat behind King in class, and then pulled the trigger. In her bid to prove a hate crime, Fox has shown drawings of Nazi images found in McInerney's notebooks and has brought in a white supremacy expert to argue that the defendant was influenced by an ideology of hatred that includes despising homosexuals. (Fox, King's adoptive father Greg, and the King family attorney Steve Pell all declined interview requests from TIME.)

On the other side, defense attorney Scott Wippert is pulling out all the stops to convince the jury that it was manslaughter. First, he argues that McInerney's upbringing in an abusive home played a role in his killing of King. Second, he's blaming school officials for not doing more to prevent King from wearing feminine attire and taunting other boys, arguing that such behavior pushed McInerney to an emotional breaking point. Third, he says the defendant's extreme emotional state made him unaware of his actions. Finally, Wippert says King's advances amounted to sexual harassment and were partly responsible for the shooting. Witnesses have said King came to school wearing women's accessories like make-up and high-heeled boots and made flirtatious comments to McInerney such as "Love you baby!"

For the jury, it may come down to a question of whether people are fully responsible for their actions. It's a hard sell to argue that the behavior of other people can actually cause someone to kill. But Wippert is trying. "Is there responsibility that goes further than Brandon? Absolutely," he said in an interview with TIME. Prosecutor Maeve Fox is having none of it. "This entire defense is built on a bias against the victim, and this hope that people will buy into the fact that the way he was and they way he dressed was so provoking that a reasonable person would have reacted the way the defendant did," Fox said in court. "It's tragic and nauseating at the same time."

Gay rights advocates and some experts say Wippert is using what's known as "gay panic defense," where the defense argues that a gay person's sexual advances are so frightening that they lead the perpetrator to commit violence. "It is blaming the victim," says Courtney Joslin, a law professor at the University of California, Davis. UCLA law and education professor Stuart Biegel adds, "These unseemly efforts to discredit Lawrence King, who was brutally mistreated and then killed, should be rejected by any jury." Biegel, who has written about the case, also says that King's behavior didn't amount to sexual harassment, and that he was merely responding to bullying by McInerney and other kids.

According to media reports of classmates' testimonies, boys at the middle school, including McInerney, would make fun of and insult King with derogatory slurs because he was gay and wore women's accessories. At lunchtime, boys eating at a table would scatter if King asked to sit with them, one friend said. Fox has said King was bullied by other boys for years and only had girls as friends. He would then flirt with the boys in order to get even because he knew it bothered them, the classmates said.

Still, the defense's approach could prove successful because similar arguments have worked in some other cases, Joslin says. In 2004, three men accused of killing a transgender person in California got a mistrial after their attorneys invoked a panic defense. After that, the state then passed the Justice for Victims Act, which was sponsored by gay-rights group Equality California, in a bid to dampen the use of such tactics. Fox has said she will invoke that law and instruct jury members not to let bias against King's sexual identity influence their decision. The defense attorney, for his part, denies that he is using gay panic. "The defense is that he was being targeted and he was being sexually harassed by this other boy, who just happened to be gay," Wippert says.

Wippert's strategy seems to be gaining traction — at least in local media and op-ed pages. The headline of a recent Los Angeles Times story said the school's decision to allow King's behavior had come "under scrutiny," while an opinion piece and readers' comments in the local Ventura County paper, where Oxnard is located, said school officials were at fault for allowing King to dress as he did. One Ventura reader wrote in to say that McInerney shouldn't be convicted of a hate crime. An opinion piece in the same paper said McInerney was as much as a victim as King because his father was a drug addict and — as witnesses have corroborated — was physically and verbally abusive toward his own son.

Will the jurors buy the defense arguments? A jury of one's peers can be just as susceptible to emotional factors as anyone, says Brian Levin, a civil rights attorney and criminal law professor. "It can pull the jury to interpret the facts in the most sympathetic way to a defendant," says Levin, who is director of hate and extremism studies at California State University, San Bernardino. "If that's done, manslaughter is a really big split-the-difference verdict." It could help McInerney get less time in prison. Closing arguments are scheduled for Thursday, Aug. 25 and the jury gets the case immediately.