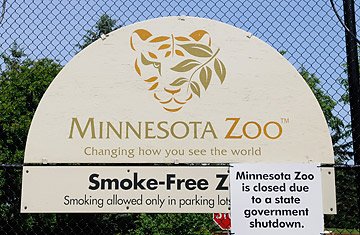

Thanks to the Minnesota-government shutdown, the Minnesota Zoo was closed for two days before reopening on July 3

One place to measure the impact of the Minnesota-government shutdown is at a truck stop in Hudson, Wis., a small border town that hugs the banks of the St. Croix River, which separates a state with a budget from a state without one.

Truckers have been flocking to the Wisconsin stop, part of the national chain of TravelCenters of America, because the Minnesota-government shutdown has led to the closure of all the rest stops in the state, making it harder to find areas for truckers to catch rest that is required by federal regulations. Indeed, business is booming around the stop despite the fact that the gas pumps are under construction. "I was reading about the shutdown in USA Today in West Virginia," says Dennis Michaluk, 47, a trucker with American Emergency Response Training, finishing up the last of his eggs and toast at a 24/7 diner. "'Hmm, that's interesting. That's where I'm going,' I thought. 'Well, I've got to stop in Wisconsin.'" Michaluk put about $800 in fuel in a 2005 Columbia Freightliner — lost revenue for the state next door that, with a $5 billion budget deficit still not closed, could use all the earning it can get.

Welcome to the shutdown land, day 11, where state troopers continue to roam the highways looking for illegally parked truckers and other violators of state law. The services the Minnesota government has been willing to cede and not cede have frustrated many. State troopers, deemed a "core function" of the government, still enforce laws on the roads, but the roads they patrol are less safe; 22,000 state employees are indefinitely jobless, but many of the lawmakers who put them in that position because they missed a budget deadline are collecting paychecks. Brian Lindholt, 33, a transportation generalist for the Minnesota Department of Transportation, was deemed nonessential and is out of work. He's relieved that the state is still paying health benefits because his daughter just got braces. But, as the political fighting plays out at the state capitol with no deal in sight, there's also still no paycheck in sight for thousands of state employees like him. "I'm worried about when I'm going back to work and how I'm going to pay the bills," says the father of three, who not only pays child support but also cares for his sick father. "We love our work, and we've showed up to do our job. Now it's time for the legislators to do their job."

Nobody knows what the economic impact of the shutdown will be until the government reopens. But add all the indicators — lost revenue from closure of the state lottery, lost revenue from closure of state parks, lost purchasing power of laid-off state employees, lost revenue from the truckers opting to patronize fueling stations across Minnesota's borders — with the fact that lawmakers are nowhere near an agreement, and the equations appear bleak. One of the more serious impacts that the shutdown has had on the Minnesota economy is the downgrading of its debt by Fitch Ratings, making it more expensive for the state to borrow money.

"Put aside your differences and look out for your folks and your visitors," Michaluk, the trucker, says in a message to Minnesota's political leaders. It's not looking like that is going to happen soon. With shades of Washington's debt debate, Minnesota's impasse has Governor Mark Dayton, part of the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party (DFL), wanting to raise revenue by taxing the top 2% of earners in the state. He recently conceded his position during the shutdown, offering Republicans a tax increase on earners making more than $1 million annually. GOP lawmakers in control of the legislature, some of whom face 2012 elections, say they don't have the votes to raise taxes and grow government at rates they think is unsustainable. Dayton, who doesn't have to face voters until 2014, recently offered a cigarette-tax increase for revenue; the GOP again rebuffed him. Many, like a bipartisan committee of Minnesota's political leaders from the old guard, including former Democratic Vice President Walter Mondale and former Republican governor Arne Carlson, fear lawmakers will once again rely on budget gimmicks — like delaying payments to K-12 schools, as DFL lawmakers did with Republican Governor Tim Pawlenty in the past. The committee has recommended that lawmakers come to a deal through service cuts and tax increases, but it fell on deaf ears with Minnesota's elected officials.

So the nation's longest shutdown in at least a decade drags on. Services funded by the state are now at the hands of an ad hoc court, presided over by a special master, former chief justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court Kathleen Blatz. She's been hearing the pleas of citizens, nonprofits and contractors arguing for the continuing flow of state payments and passing them on to Judge Kathleen Gearin, of Ramsey County District Court, who has the final say. Many services, like state aid training for the blind and the Minnesota Zoo, have successfully petitioned the court. On Friday, the court denied the petition of the nonprofit Arc of Minnesota, which receives state grants to provide housing-access services to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Its services, which include making referrals to the disabled homeless, might soon cease if the shutdown drags on, says public-policy director Steve Larson.

Lindholt, the out-of-work state employee, has already seen the impact of the shutdown on the state's roads, where his co-workers had been busy fixing pavement that often buckles or explodes during Minnesota's hot summers. Now orange barricades dot highways across the state, a reminder of abandoned construction projects. And there might be fewer truckers transporting goods and services on those highways. Midwest Specialized Transportation, an overland carrier based in Rochester, Minn., with a fleet of 115 trucks that drive long legs through the continental U.S. and Canada, has seen its freight tonnage increase as the economy slowly pulls out of the recession — just like the rest of the trucking industry. General manager Sean Claton says the company recently invested in a dozen trucks to replace old ones and to expand its fleet — in normal times, it is a sign of recovery. But the Minnesota political gridlock is hampering that recovery. The company cannot obtain licenses because the Minnesota Department of Transportation is not providing that service. Meanwhile, the Minnesota Trucking Association is awaiting a decision from the special master to reopen credentialing and rest stops.

Claton estimates that for every day the trucks sit idle, the company is losing $5,000 in top-line revenue. "I've made a multimillion-dollar investment in our business, purchasing equipment. I've got drivers for those trucks. I've got customers purchasing freight for those trucks. But I can't put those trucks to work," he says. "The economy is at a pretty precarious point right now, and I think the last thing you want to do is negatively impact the movement of goods and services through it."