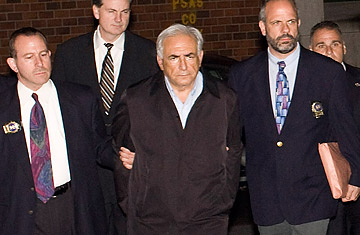

Dominique Strauss-Kahn is walked to a police vehicle outside a New York City Police Department facility on May 15, 2011

It's hard to think of much good coming out of Dominique Strauss-Kahn's alleged sexual assault on a hotel maid, but there is this: the case is creating momentum to end the "perp walk," in which defendants are paraded before news photographers and made to look guilty before the case against them even begins.

When Strauss-Kahn, the rich and powerful head of the International Monetary Fund, was arrested in May on attempted rape charges — which prosecutors may now be close to dropping — he was marched handcuffed and unshaven in front of a scrum of waiting media, grimacing as the shutters clicked. The perp walk, short for perpetrator walk, is an entrenched American tradition — Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald was on one when Jack Ruby shot him dead. But Strauss-Kahn's perp walk caused an uproar in his native France, where such displays are regarded as serious infringements on defendants' rights. The philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy captured the pitched level of the outrage when he assailed perp walks as "cannibalization," "globally observed high torture," and "not just cruel" but also "pornographic." The Conseil Supérieur de l'Audiovisuel, France's television watchdog, sent an advisory out to networks reminding them that it was illegal to broadcast images of a defendant in handcuffs if he had not been convicted.

In the U.S., there has not been anywhere near this level of outrage. The practical reason for perp walks is the need to take newly arrested prisoners from one location to another, often from the police station to court. But in recent years they have become something of an art form: law enforcement often tip off the media so they can be assured of heavy coverage. Defendants are typically handcuffed, no matter what crime they are charged with or their likelihood of escaping from an armed police escort — Susan McDougal, who was jailed for not testifying in the Whitewater investigation, had a famous perp walk in leg irons outside an Arkansas courthouse.

Perp walks happen across the country, but they are most closely associated with New York City. When Rudolph Giuliani was the top federal prosecutor in Manhattan, he used them against mobsters and white-collar criminals, grabbing big headlines. And they do make a splash: an iconic photograph of David Berkowitz, the serial killer also known as the Son of Sam, was captured on a perp walk. John Gotti, the mob leader known as the Dapper Don, dressed up for his perp walks. The actor Russell Crowe sported sunglasses for his.

Perp walks have their defenders, who argue that they bring transparency to the criminal-justice system and show that no one is above the law. But civil libertarians have long argued that they amount to a public shaming of arrestees who have not been convicted of anything — and may never be. Worse, they plant an image of guilt in the minds of people who see them: the very same people who may later serve on the defendant's jury.

The concern about making defendants take on the physical trappings of guilt has a long history in the law. As early as the 18th century, the great legal commentator William Blackstone invoked an "ancient" principle that defendants "must be brought to the bar without irons, or any manner of shackles or bonds; unless there be evident danger of an escape." In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled in Estelle v. Williams that a defendant cannot be required to stand before a jury while dressed in identifiable prison clothes because it undermines the presumption of innocence and denies him a fair trial. In today's media age, the perp walk does the same thing, prejudicing members of the jury before they have even become the jury. In 2000, a federal appeals court in New York ruled that the police could not force an arrested person to undergo a staged perp walk — something the court said presented a "powerful image of guilt" — unless it serves a genuine law-enforcement purpose. The ruling allows perp walks when there is a legitimate need to move a prisoner — like taking him to a court appearance — and those are the sort of perp walks done in New York today.

In the past few weeks, the case against Strauss-Kahn appears to have unraveled. Prosecutors have determined that the hotel maid who accused him has "substantial credibility issues," and there is talk that the case could be plea-bargained away or dropped. The more doubts there are about Strauss-Kahn's guilt, the worse his perp walk looks. New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently called perp walks "outrageous," saying: "They're not guilty until they're convicted, and yet we vilify them for the benefit of theater, for the circus. You know, they did it in Roman times too." A New York City councilman, David Greenfield, plans to introduce a bill to prohibit perp walks, declaring, "Even Mother Teresa dragged out by detectives would look guilty."

The perp walk is unlikely to go away easily — New York City's police commissioner Ray Kelly is defending them as simply "how we transport people to court." And the media would miss them a lot. It is time, though, to recognize that whatever their benefits, perp walks can do irreparable harm to a defendant's right to a presumption of innocence and a fair trial.

Cohen, a former TIME writer and a former member of the New York Times editorial board, is a lawyer who teaches at Yale Law School. Case Study, his legal column for TIME.com, appears every Monday.