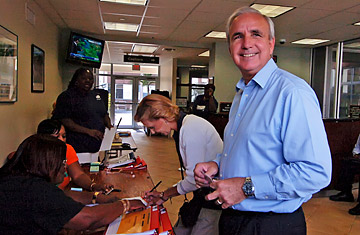

Carlos Gimenez, a candidate for mayor of Miami-Dade County and wife Lourdes vote in Miami, Florida, during a runoff election Tuesday June 28, 2011.

Miamians hate it when media criticism of their city is couched in stale clichés like "Trouble in Paradise" or "Paradise Lost." I agree: it's time to nix the whole "paradise" chestnut, because Miami isn't and never really was paradise. In fact, it was originally a mangrove swamp; South Beach is entirely man-made. Yes, Miami winters are balmy, but have you ever spent an entire summer here? By August you're dreaming of Montreal.

But put aside Miami's natural attributes and consider its civic qualities, and things get really infernal. In March, the voters of Miami-Dade County, or metropolitan Miami, recalled their Mayor, Carlos Alvarez, who during the worst recession since the Great Depression gave his top staffers pay raises as high as 15% while using his government car allowance to help pay for his new luxury BMW. In the June 28 run-off election to replace Alvarez, the choices were a Hialeah politician under federal investigation for alleged loan-sharking (he denies it) and a member of the Miami-Dade County Commission, a body so clueless and cavalier that one of its members heads a construction company that gets contracts from Miami International Airport — which the Commission oversees.

Just last week, Miami's embattled police chief, Miguel Exposito, claimed that city officials offered him $400,000 to resign. Of course other U.S. cities, like Chicago, have corrupt government. But Chicago can afford it better because it has a real economy. Miami doesn't, which is why its unemployment rate is still mired at 13.7% while other Florida metropolises like Tampa (10.5%), Orlando (9.9%) and Jacksonville (9.7%) are emerging from the crisis. You'd think, with such problems, that Miami-Dade's 1.2 million voters would have come out in force on Tuesday to select their new Mayor, who turned out to be the Commission member, Carlos Gimenez. But turnout was a shameful 16%. "We just don't yet have the civic maturity of the major city we're supposed to be," says Dan Ricker, publisher and editor of the Miami-based WatchdogReport.net.

And Miami is supposed to be a major city: no less than the trade and cultural nexus of the Americas. Instead it more often seems a municipal version of the old joke about Brazil: that it's the country of the future — and always will be. Brazil has since grown out of that feckless reputation, but Miami just might inherit that mantle.

Miami faces the same problem that has always nagged developing countries like Brazil: the gap between its low wages and its high costs of living is one of the widest in America. Even in the 21st century, the Magic City still lives under its 20th-century illusion that tourism and condo construction are the basis of a modern economy. Nor has Miami found a way to turn its robust trade and banking sectors — some $95 billion worth of imports and exports moved through Miami last year, a 21% increase over 2009 — into equally vigorous job-creation engines.

Florida on the whole is still far too low-wage and low-tech. But Tampa, by comparison, has pared a recession unemployment rate that stood at 13.1% last year largely because it's encouraging the kind of industries, like bioengineering, that ought to be blooming in a city that has Miami's large number of hospitals and elderly retirees.

But they aren't, and that's in large part the product of an abysmal leadership, like the Miami city officials who, despite a hiring freeze to help stanch municipal red ink, went ahead and recently made 200 new hires anyway. Miami-Dade desperately needs charter reform, but Commission members sabotaged approval of many amendments presented to voters in May. While they rightly proposed, for example, that members receive a $92,000 annual salary instead of the ridiculous $6,000 they get now — which is a big reason the Commission doesn't attract more honest and talented candidates — they tried to grandfather in a 12-year term limit that could have let some current members serve into the 2020s, a prospect too appalling for most Miami voters.

Miami-Dade Mayor-elect Gimenez, who will finish Alvarez's term until an election in November 2012 — and who faces a $239 million county budget deficit — "can at least restart the process" of charter reform, says Ricker. But unless he wins the 2012 race as well, what Gimenez won't have time to rectify is Miami's other key ill: its community balkanization. For all its potent immigrant energy, Miami still seems less a city than a collection of antagonistic ethnic enclaves separated by sprawl (public transportation remains virtually non-existent) and a lack of common purpose. That was all too evident when a group backing Gimenez, an affluent Cuban-American, went trawling for white and non-Latino voters by airing an ad (which Gimenez has less than convincingly disavowed) painting Hialeah, a working-class Cuban-American community where Gimenez's opponent, Julio Robaina, was mayor, as a seedy swamp of political crooks.

It was also a reminder that Miami's most gaping breach is between rich and poor. Less than a fifth of Miami-Dade's population inhabits the middle class, and the city of Miami has one of the U.S.'s highest poverty levels. Yet Miami-Dade consistently ranks among the top 10 U.S. counties in the number of millionaires. The Miami Heat's embarrassing choke in the NBA finals this month proved that overpaid showboats don't necessarily win championships. Nor do they make you a major city.