Modernist Cuisine

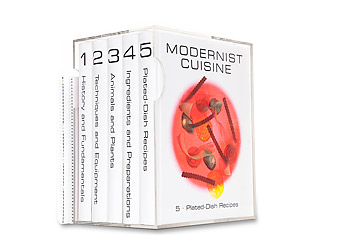

It's only natural, I suppose, for a $625 five-volume, epochal publishing event like Nathan Myhrvold's Modernist Cuisine to polarize the food world. After all, this is the book the whole culinary world has been waiting for: "the cookbook to end all cookbooks," as David Chang called it. I witnessed Myhrvold's impatience with old-fashioned ways of thinking when I visited the eccentric millionaire last fall, and so last week's dustup with superstar food writer Michael Ruhlman wasn't unexpected. But it told a lot about how Modernist Cuisine is being misunderstood, and even misrepresented in some ways.

To recap: Ruhlman reviewed Myhrvold's magnum opus for the New York Times, and found it "mind-crushingly boring, eye-bulgingly riveting, edifying, infuriating, frustrating, fascinating, all in the same moment." Ruhlman recognized the immense contribution the book makes to culinary knowledge, and no serious student of food doubts that it will stand alongside Escoffier as one of the defining cookbooks in history. But Ruhlman, like many traditional cooks, sees it as a playground for chefs and food geeks rather than the revolution Myhrvold had hoped for. "Can this truly be the food of the future," Ruhlman asked rhetorically, "or simply an interesting style practiced by a splinter group of passionate chefs who care about this difficult and expensive form of high-end cooking?" He saved his heaviest stroke for last: "Much of this revolutionary cooking is based on ingredients and techniques long fundamental to the processed food industry. Are we to embrace the ingredients and techniques of modernist cuisine at the very moment industrially processed food is being blamed for many of our national health problems?" Ruhlman wasn't the first food writer to rebel against Myhrvold's technological gospel. Alice Waters, always ready to reassert the Naturalist party line, came out against the book months ago, but Ruhlman's review appeared in the Times, and so it has the weight of the official Establishment response behind it.

Myhrvold, not one to take a dismissal lying down, thundered back in a widely quoted post on the popular food forum eGullet. Though taking pains to parse Ruhlman's equivocating rhetoric and refute an easily checkable claim that all the meat in the book is cooked sous vide (it isn't), he shot back that Ruhlman "panders to the natural food movement," a group Myhrvold sees, not without reason, as a bunch of primitivists and Luddites.

This is not to say that the response to Modernist Cuisine has been uniformly negative. Far from it. But even when it's praised there seems to be an edge. The most thoughtful and sympathetic piece on the book that I've seen was by Helen Rosner in Saveur, who admired the marginalized Myhrvold's vast undertaking. "In the current culinary landscape — one that's dominated by an obsessive, virtue-driven concern for provenance, sustainability, and rustic simplicity," she writes, "a multi-thousand-page book full of impenetrable science writing isn't going to land lightly." Oh, so that's what it is! The dichotomy has been set up between honest naturalist chefs on the one side — people who "cook from the heart" and touch the soil — and on the other, cerebral nimrods who live in a la-la land of gels and immersion circulators. Given this choice, what chance is there that the public will sympathize with the latter?

Which is a shame, because despite Myhrvold's geeky attachment to high-tech tools like centrifuges, ultrasonic baths and the like, his book is much more than a molecular manifesto. As he told me again and again while I was interviewing him for TIME's article, he wasn't out to justify weird stuff, he wanted people to understand food and to be better at cooking food — even people who weren't going to use his tools. It was impossible, given who he is, that he wouldn't produce a book that was the final word on high-tech cookery; he's one of the most brilliant and influential technologists in the world, the man who used to be called Microsoft's brain, who studied mathematical astrophysics with Stephen Hawking and who, when not writing cookbooks, helps develop lasers that can shoot the wings off mosquitoes. But there's a reason that only one chapter of one book is devoted to "The Modernist Kitchen."

Myhrvold, and the book's audience as well, aspires to cook better food — not weirder food, not more surprising food, but food that's just better. This is the book you read so you understand what's going on inside your brisket as it sits in your smoker, why eggs act the way they do when they're in a pan, and how moist air cooks differently from dry air. Those are the real aims, and the real achievements, of Modernist Cuisine. The food media really ought to refrain from taking cheap shots; the book could, and should, teach all of us a lot about food, and if it fails, maybe it's because its critics didn't try hard enough to understand it.

Ozersky is a James Beard Award–winning food writer and the author of The Hamburger: A History. You can listen to his weekly show at the Heritage Radio Network and read his column on home cooking on Rachael Ray's website. He is currently at work on a biography of Colonel Sanders.