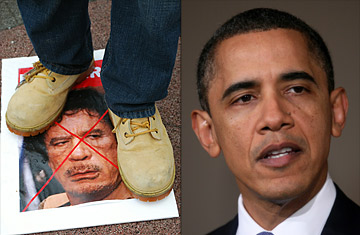

A protester stands on a picture of Gaddafi during a demonstration in Chicago, left; Obama delivers a statement condemning the ongoing Libyan violence

It seems preposterous to suggest in the wake of Iraq that the U.S. might intervene militarily to help bring down another Arab regime. But the growing danger of a humanitarian catastrophe created by Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, combined with a surprisingly broad confluence of interests, has crisis watchers inside and outside the Administration seeing the telltale signs of a conflict that could compel Obama into action. "It's increasingly imaginable that there would be some kind of international intervention in Libya, and I think the U.S. would be active in shaping that," says James Dobbins of the Rand Corp., a veteran of nearly all U.S. humanitarian interventions over the past two decades.

If international consensus emerges for military intervention to save Libyan lives from a regime lashing out in its death throes, it would not be led by the U.S. unilaterally, a senior Administration official tells TIME, but rather would be under the auspices of the U.N. "Discussion of any military accompaniment [to an aid mission] would have to take place in New York through the Security Council," the official says. "Right now, we're looking to lay the predicates for stepping up if that's required." The official says so far there has been no push back from the Pentagon on any contingency planning, including the cataloguing of military assets available for deployment in Libya. For now, the focus is on providing humanitarian assistance to those in need. But since the fall of the Berlin Wall, such missions have often expanded to include not just protection but also active military intervention.

The first reason to believe the U.S. and its allies may intervene in Libya is Gaddafi: "You start from the premise that he's crazy," says the senior Administration official. Add his refusal to go quietly (on Monday he told ABC's Christiane Amanpour that he could not step down because "my people love me; they would die for me"), his bristling arsenal in the hands of ruthless mercenaries and other loyalists, and his massive reserves of oil wealth with which to pay them, and you have an international pariah capable of committing the kinds of atrocities that have prompted international intervention in places such as Somalia and Bosnia. It's the scale of murder and mayhem that Gaddafi is capable of unleashing that has Washington focused on behind-the-scenes efforts to oust Gaddafi. "Getting him out is key," says one U.S. official.

But if the Libyan dictator can't be forced out, and if he continues to kill civilians and fuel massive population flight, the international community will feel growing pressure to act. As hundreds of thousands of people flee the country and members of the diffuse Libyan opposition call for help, the U.S. is already well on the way to joining an international response. USAID's Rapid Response teams are headed for the Egyptian and Tunisian borders with Libya. On Tuesday, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees will issue an appeal for an initial $15 million from member states to fund relief efforts, and spokesperson Melissa Fleming says the U.S. has indicated a willingness to help.

The Administration is preparing more intrusive measures. The senior Administration official tells TIME that planning is well under way for opening humanitarian corridors into Libyan territory. The U.S. has discussed the possibility of NATO air forces imposing a no-fly zone over Libya, and is also considering radio-jamming measures, senior U.S. officials say. On her way to Geneva for talks with members of the U.N. Human Rights Council, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said Sunday that the U.S. stood ready to offer "any kind of assistance that anyone wishes to have from the United States" in the effort to oust Gaddafi. In Geneva on Monday she said, "Nothing is off the table so long as the Libyan Government continues to threaten and kill Libyans."

Humanitarian missions of the type now taking shape for Libya turned into more challenging military operations in Somalia, Bosnia and Kosovo during the 1990s. The most traumatic example of mission creep came in Somalia during the transition from the presidency of George H.W. Bush to the Clinton Administration. The absence of a clear sense of what might come after a Gaddafi ouster raises fears of a repeat of the Black Hawk Down scenario, in which military forces supporting a humanitarian mission got caught up in a vicious local power struggle.

Still, the forces favoring a robust humanitarian intervention in Libya are surprisingly broad. Administration figures such as Hillary Clinton; Samantha Power, a senior director at the National Security Council; and Susan Rice, the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., have experience with the genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia, and are sensitive to the urgency of responding decisively. Some also see an opportunity to rehabilitate the U.S. role in international humanitarian intervention, which Power told TIME in 2006 had been "killed for a generation" by the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

Outside pressures exist too. European energy companies are deeply invested in Libyan oil and gas fields, which yield significant percentages of their production. U.S. counterterrorism officials have noted the disproportionate number of Libyans turning up in the ranks of al-Qaeda both in northern Africa and in Iraq. Domestically, Republicans like Senator John McCain have criticized Obama for not doing more in Libya, and potential GOP presidential candidate Newt Gingrich argued in 2005 for international intervention to end war crimes even without U.N. approval. "In certain circumstances, a government's abnegation of its responsibilities to protect its own people is so severe that the failure of the Security Council to act must not be used as an excuse for the world to stand by as atrocities continue," Gingrich wrote at the time.

Some inside the Administration fear the implications of the growing momentum for action. "What scares me about this is you could have a bunch of people who want to intervene — a weird coalition with short-term agreement on intervention but zero long-term end-state agreement," says one U.S. official familiar with the discussions. Adds Rand's Dobbins: "What we've learned over the last 20 years is that overthrowing objectionable governments is easy; replacing them with something good is hard. The U.S. doesn't want to get saddled with the transition."