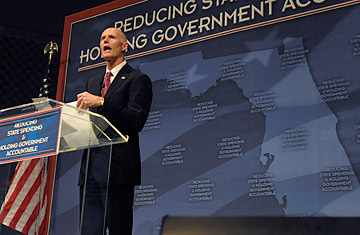

Florida Governor Rick Scott announces his new budget during a Tea Party event in Eustis, Fla., on Feb. 7, 2011

Shortly before Governor Rick Scott was sworn in in January, a report showed that Florida had the U.S.'s leanest state workforce — 117 employees per 10,000 residents, compared with a national average of 215. That reality seemed to challenge the urgency of Scott's campaign promise to cut 5% of that workforce as part of his crusade to significantly reduce government spending.

Still, a pledge is a pledge, especially when your Republican base is angry, antigovernment Tea Party voters who helped you squeak through to victory in November. So last week, Scott — speaking not from the state capital, Tallahassee, but from the Tea Party hotbed of Eustis, Fla., to show his disdain for all things public sector — delivered a budget proposal that slashes $4.6 billion (7% of current spending) and pink-slips 8,700 state employees, while gutting aid for disability services and juvenile justice.

"Reviewing a government budget is much like going through the attic in an old home," said Scott, a health care industry multimillionaire who resigned in disgrace as CEO of the world's largest hospital corporation in 1997, when it was accused of massive Medicare fraud (though he never was). "And I'm cleaning it out." That drew roars from the Tea Partyers jammed into the First Baptist Church of Eustis, who, like Scott, believe that bulldozing the budget has to be part of his "7-7-7" mission: seven steps to 700,000 jobs in seven years.

But in a state where unemployment topped 12% last year, the idea of jettisoning such a large number of workers wasn't received as well outside Eustis, no matter how loudly Scott insisted that his way would beget far more employment in the private sector. In Tallahassee, even fellow Republicans, who control the legislature and are trying to plug a more than $3.5 billion hole in the budget, considered Scott's budget, including his rejection of remaining federal stimulus dollars, nonsensical. "It's imperative that you go back and you redo the numbers," GOP state representative Janet Adkins told a Scott aide at a hearing. Adkins was questioning Scott's 15%, or $3.3 billion, cut in education spending at a time when the school reforms and funding of his predecessors in office, Republican Jeb Bush and independent Charlie Crist, are starting to show improvements.

It was an especially important warning, not just for Florida but also for the rest of a nation trying to absorb the meaning of November's Tea Party phenomenon. While closing perilous budget deficits certainly has to be a priority today, there's a big difference between mopping up red ink and rubbing out state government. Scott has made the latter his war cry since he started spending almost $75 million of his own fortune last year to capture the country's fourth largest statehouse. But a budget proposal like his does more than try to eviscerate a state apparatus that already costs its residents — who, by the way, pay no state income tax — less than any other U.S. residents pay ($38 per resident, vs. a national average of $72). More important, it may also work against his own crucial goal of creating jobs.

Florida is often held up as America's new bellwether state — the California of the new century. But it can't possibly realize that potential as long as it remains a low-tech, low-wage economy inordinately reliant on beaches and oranges, unable to bridge the large gap between what people earn there and what it costs to live there.

To take Florida into the 21st century, Scott wants to make it a haven for business. That sounds reasonable, except in many ways it already is: it has one of the nation's lowest corporate tax rates, and developers have long had the run of the peninsula. Yet Scott wants to phase out the corporate levy as part of his scheme to reduce taxes by $4 billion; he hopes to make up that lost revenue by making state workers contribute to their pension plan — and in his defense, Florida is one of the few remaining states where government employees don't pay into their retirement system.

The point that Scott and his conservative philosophy miss is that a state can't become a real haven for business just by sweeping taxes off the table. It has to put commitments on the table too. Certainly no one would hold up California's state government, currently broke, as a model today. But back when California, the country's largest state, was doing things right, it was investing in the things that attract high-tech business and high-wage jobs — including infrastructure but especially education, from preschools to research universities. The average teacher salary in California hovers around $70,000; in Florida it's $50,000. California has five universities, both public and private, in the U.S. News & World Report ranking's top 25 and nine in the top 50; Florida has just one in the top 50, at No. 47. One key result: 6.6% of California's workforce hold high-tech jobs, compared with 3.2% of workers in Florida — where among the 10 most common jobs, only one, nursing, offers an hourly wage of $15 or more.

Despite the ideological certainty of Scott and the Tea Partyers, Florida's private sector can't change that situation all by itself, just as government surely can't. A partnership of the public, the private and the academic can, as California's Sacramento–Silicon Valley–Stanford paradigm did for so many years. To his credit, Scott seems to understand at least part of that equation: one of his seven steps is "investment in world-class universities," which he sees as incubators for the biotech and green-energy industries that could and should thrive in Florida.

And yet state university education and research would see a $217 million cut under Scott's budget, while state college and vocational programs would be trimmed by $123 million. Again, Republicans themselves were the first to weigh in after Scott's swearing-in: "How does that help the [Florida] workforce get back to work?" state house Higher Education Appropriations Subcommittee chairwoman Marlene O'Toole asked. Such questions indicate that the legislature isn't likely to produce a budget that looks even remotely like the first hand of cards Scott dealt.

Scott's well-timed rebuttal was the Feb. 10 announcement by hydrogen-fuel-cell company Bing Energy Inc. that it will place its headquarters and production facilities in Tallahassee — lured largely by his promise of corporate tax cuts. Scott took part in the press conference, savoring the symbolism of a private-sector show of strength amid the Tallahassee Gomorrah of government waste. It only helped his case that Bing, which plans to employ 250 workers, uses technology developed at Tallahassee-based Florida State University. "My commitment is [to] make sure we have many, many [similar announcements] around the state," Scott said. He'll need many, many more to vindicate the kind of draconian budget he unveiled last week.

With reporting by Michael Peltier / Tallahassee