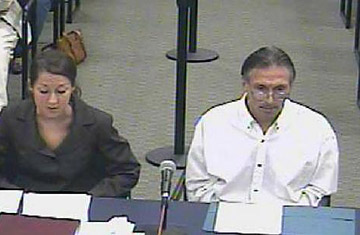

Dominic Cinelli before the Massachusetts Parole Board in 2008

In painful retrospect, it can be said that Dominic Cinelli had a penchant for crime. In fact, during a one-day furlough from prison in 1985, he went AWOL and committed five robberies. But in 1986, he was sentenced to three consecutive life terms. Ostensibly, that would have been the end of the career criminal's reign of terror in Massachusetts. Yet, the day after Christmas 2010, Cinelli shot and killed a Woburn police officer during a robbery attempt at a Kohl's department store. No, Cinelli hadn't been given another day-long furlough. He had actually been paroled by the state two years earlier — and three lifetimes before he was originally set for release.

The Cinelli case brought the issue of the life sentence to the forefront just as the nation entered its traditional commutation season. Right before the new year, suspensions of life sentences were ordered for two Mississippi sisters who were in prison for their part in an armed robbery of $11 (it was contingent on one sister giving the other — ailing — sister a kidney). In his last days as Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger commuted the life sentence of a woman convicted of killing her pimp when she was a teenager. Rather than never have a chance to leave prison, she will now be eligible for parole in nine years.

As states and governors utilize a host of different parameters to define life sentences, has the penalty become an arbitrary science and a complete misnomer? Do states need to re-evaluate and revamp their parole and commutation standards?

In the U.S. there are basically two kinds of life sentences: with or without the possibility of parole. But if someone is serving a life sentence with the possibility of parole, how do states decide who to release? Parole standards tend to differ between states and sometimes can appear a bit mercurial. In Nevada, the state utilizes a point system as part of its parole process to determine the risk factor that a criminal poses; the lower the score, the lesser the risk. Having a GED, or high school or college degree is worth -1 point, while being under 21 is worth +2 points. Additionally, being female doesn't affect your score, while being male adds +1 point.

And then politics and ideology play a role. Take Massachusetts, the state that paroled Cinelli, for an example. According to Boston's NPR affiliate WBUR, back in 1999, while the state's parole board was under Republican appointees, just 13% of prisoners serving life sentences received parole on their first attempt. Ten years later and under a Democratic administration, 32% of those serving life sentences have been granted parole on their initial try.

It's not just a problem in the United States, as many countries abroad have wrestled with the issue. In Europe, some countries such as Portugal and Norway have completely done away with the life sentence in lieu of longer and fixed prison terms. In the Netherlands, those serving life sentences are never given parole — though the penalty is very rare. Most murderers there are punished with 12-to-16 years in prison. Additionally, like the United States, Europe has been no stranger to the debate on paroling violent offenders. Last year in Finland, a convicted murderer on parole shot and killed three people at a McDonald's.

UC Berkeley law professor Jonathan Simon says that the U.S. might benefit by looking at the British approach to the life sentence. "While life is the mandatory sentence for murder [in the U.K.], it is up to judges to set what is called the 'minimum tariff,'" says Simon. "This is intended to reflect the retributive and deterrent punishment appropriate to a crime. After that minimum, the sole reason that person should continue to be confined is that they continue to pose an unacceptable risk to the public, because of their prison conduct, their psychological evaluations, or their failure to seek rehabilitative programming in prison."

Experts warn that would-be reformers shouldn't tinker too much with existing rules regarding parole and commutation, if only to allow for injustices — or egregious punishments — to be righted. For example, in 2003 a group of students and a professor from Fordham Law School managed to overturn the sentence of a woman convicted of pickpocketing. She had received a sentence of 20-to-life.

Other experts, however, caution that the Cinelli case is an abnormality. "When a disaster like this happens, general statistics are no consolation," says Robert Weisberg, director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center. "But violent recidivism by paroled lifers is very, very rare, in part because so few get through the vetting and in part because older parolees have usually aged out of their criminogenic tendencies." Still, as the case of Cinelli shows, sometimes "life" really should really mean life.