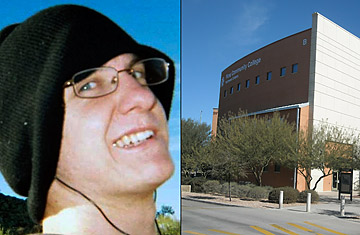

Jared Loughner, left, and Pima Community College

In retrospect, it's easy to see the evidence that Tucson, Ariz., shooter Jared Loughner was mentally unstable. In his community-college classes, he would laugh randomly and loudly at nonevents. He would clench his fists and regularly pose strange, nonsensical questions to teachers and fellow students. "A lot of people didn't feel safe around him," a former classmate told Fox News.

Given these facts and the horrific turn of events at a Safeway supermarket on Jan. 8 that left six dead and 14 others injured, including Representative Gabrielle Giffords, who remains in critical condition, could anything have been done to prevent the violence? What signs that trouble lay ahead were missed? What signs were observed but ignored? In short, what can be done to prevent a potentially ill or unstable person from harming others?

In most states, including Arizona, it's predictably difficult to detain someone involuntarily due to mental illness. If he is not deemed an imminent danger to himself or others, as determined by a judge, in almost all cases, treatment will not come without the person in question admitting that they are ill and need help. Even then, there is no guarantee that help will come readily or swiftly.

"What you have is an obvious need for more capacity in the mental-health system," says Dr. Ken Duckworth, a Harvard professor, psychiatrist and medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). A need for more capacity is certainly true in Arizona. According to a 2005 report from the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nonprofit mental-health organization, the state had 5.9 publicly funded psychiatric beds per 100,000 people, compared with a national average of 17. In addition, NAMI gave the state's mental-health system a C in 2009, a step up from its D grade in 2006, but with vast room for improvement. Part of Arizona's low marks stem from its large Native American and foreign-born populations, which are harder to reach and treat, as well as the state's rapid overall population growth and rural regions, which are underserved by medical professionals. Still, the state was not an outlier. In 2009, NAMI gave just six states B grades, while 18 got Cs, 21 got Ds and six got Fs. None received an A.

Regardless of resources available, however, the problem with someone like Jared Loughner is that, without a court order, he would not have received treatment without a self-referral. It appears that his community college, which kicked him out, rightly protected its own population — at least one student and one teacher told the New York Times they feared Loughner would bring a gun to class — but left the rest of the community vulnerable. It would have been up to Loughner to seek treatment, a move many psychiatrically ill people would never make. "Most young people who develop a psychiatric illness — particularly a psychotic illness in which they've lost the ability to discern fantasy from reality — don't have a lot of insight into the fact that they are ill," says Duckworth. He points to a recent online NAMI survey that found that schizophrenics suffered an average of nine years between their onset of symptoms, which often first appear in the late teens and early 20s, and diagnosis.

Often, authorities can intervene only once the illness has taken a dramatic, if not criminal, turn. On the same weekend of the Giffords shooting, the FBI took John Troy Davis, 44, of Denver into custody for threatening the staff of Colorado Senator Michael Bennet. Davis had been a familiar voice to Bennet's office, often calling to complain about Social Security benefits. But on Jan. 6, he began to say things like, "I'm a schizophrenic and I need help," and "I'm just going to come down there and shoot you all." In a subsequent call, he claimed to have killed a woman to get the Senator's attention. He then said, "I may go terrorism." The FBI decided to move on the case.