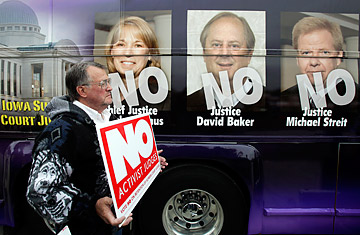

Cal Flynn holds a sign during a rally in Des Moines, Iowa, by gay-marriage opponents in favor of removing three state supreme court justices who joined in a unanimous ruling legalizing gay marriage

It was one of the more striking results from last week's elections: three Iowa Supreme Court justices who joined last year's pro-gay-marriage ruling were voted out of office. Opponents of gay marriage celebrated, confident that a miscarriage of justice had been corrected at the ballot box, but they were wrong. The removal of these three judges — all highly respected jurists, appointed by both Republican and Democratic governors — should send a shiver down the spine of anyone who cares about the American system of justice.

In Iowa, supreme court justices are nominated to the bench by the governor in a merit-based system, but the voters get a chance to decide whether to keep them on for their first term and later for any additional terms. In last week's election, voters opted to remove Chief Justice Marsha Ternus, David Baker and Michael Streit. Their ousters marked the first time that an Iowa Supreme Court justice had been removed since the system was put in place in 1962.

The three justices were targeted because last year they joined a unanimous Iowa Supreme Court in ruling that the state constitution required Iowa to recognize same-sex marriages. It was a legal decision based on pure constitutional interpretation.

To opponents of gay marriage, however, the ruling meant war. Anti-gay-marriage activists in Iowa and across the country poured as much as $800,000 into the state to attack Justices Ternus, Baker and Streit — the only ones of the judges up for a retention vote this year — for the ruling. The three justices, not surprisingly, did not raise a similar war chest or respond in kind.

The Iowa vote is just the latest evidence that elections are a terrible way of choosing judges — whether the decision is putting them in office or removing them. The Constitution's framers, who were brilliant in their sense of how government power should be allocated, had a very different idea about judicial selection. They decided federal judges should be appointed by the President and confirmed by Congress — with the people getting no say of any kind. Federal judges would then have lifetime tenure, insulating the third and equal branch of government from the pressures of the political majority.

If it sounds undemocratic, that's because it is — and intentionally so. Judges decide what people's fundamental rights are, and the founders understood that fundamental rights must not be put up for a popular vote. Judges are also responsible for protecting minority groups, which they might not be able to do if they had to answer to the will of the majority.

Federal judges' independence gives them a unique role in government — something that was clear in the civil rights era. In the 1950s and 1960s, when Southern elected officials strongly supported racial segregation, federal judges were the one powerful force in the region that could, and did, stand up for equal rights.

Frank M. Johnson, a federal district-court judge in Montgomery, Ala., integrated the city bus system and forced the state to register black voters. He was called "the most hated man in Alabama," he received regular death threats and his elderly mother's home was bombed. If Alabama voters could have voted to remove Johnson, they would have done so overwhelmingly — but because he was a federal judge, he was there for life.

State-court judges do not have the same protection. In more than two-thirds of the states, judges are either elected to begin with or eventually face the voters, as in Iowa. Judicial elections were once generally fairly high-minded, but in the past few years they have become bare-knuckle political brawls.

In a recent report, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School decried the steep rise in money spent on judicial races, much of it poured in by "super-spender" organizations that seek to influence the courts, and the simultaneous rise of vicious attack ads.

The money is almost always intended to buy justice in one way or another. Business groups funnel contributions to candidates who will let businesses trample on the rights of workers and consumers. Plaintiffs' lawyers, on the other hand, want judges who will uphold sky-high damage awards — and large attorney's fees. According to the Brennan Center, a single law firm in Alabama gave more than $600,000 to a candidate for the state supreme court, none of which, thanks to weak disclosure laws, showed up in contribution records.

The solution to this disturbing trend is appointing judges based on merit — a cause that Sandra Day O'Connor, the retired Supreme Court Justice, has adopted with great enthusiasm. O'Connor has lately been calling attention to the enormous amount of money being spent on judicial elections — and urging states to switch from electing to appointing judges. O'Connor also spoke in Iowa in September on behalf of the three justices, saying voters should not retaliate against judges who make unpopular rulings.

Last week in Nevada, a referendum that O'Connor supported to switch from electing to appointing judges was defeated. That loss and the Iowa results were the bad judicial news of this election cycle. The good news was that activists also targeted justices for defeat in Alaska, Colorado, Illinois and Kansas — and all of those efforts failed. In Kansas, justices targeted by antiabortion groups won with more than 60% of the vote.

O'Connor has been bitterly attacked by allies of big business who accuse her, wrongly, of misusing her position. The reason they are attacking her is simple: they are afraid that, in time, she may persuade enough people that states will be better off with the kind of judges the founders envisioned — ones who cannot be intimidated, who aren't subject to political whim and, most importantly, who are not for sale.

Cohen, a lawyer who teaches at Yale Law School, is a former TIME writer and a former member of the New York Times editorial board. Case Study, his legal column for TIME.com, appears every Wednesday.