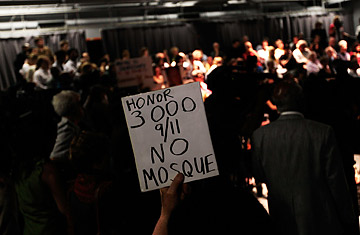

An opponent of the proposed Islamic cultural center and mosque near Ground Zero holds a sign during a community board meeting to debate the issue

Correction appended: Sept. 10, 2010

On the ninth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the area around Ground Zero will witness much more than somber remembrance. A rally protesting the proposed Muslim community center near the site will take place shortly after official memorial services end. So too will a counterprotest. In recent weeks, some families of 9/11 victims have come out against the so-called Ground Zero mosque, while many others have expressed support for its construction. The controversy has spawned myriad coalitions and action fronts: Saturday's anti-mosque rally is being conducted by the American Freedom Defense Initiative (a name that in another era could have belonged to a band of Latin American guerrillas). It has been challenged by the recently formed New York Neighbors for American Values and other pro-mosque groups.

If the debate centers on the "hallowed ground" of Ground Zero, the site itself has now become political dynamite ahead of the November midterms and a lodestone for many other pressing conversations — about freedom of speech, tolerance and the place of Islam in America. And in a sense, it's fitting that such a sweeping, emotional issue has arisen from this tiny slice of New York City. Lower Manhattan has long been one of America's most dynamic neighborhoods and a fulcrum of all the antagonisms and paradoxes that make up this diverse nation.

That story begins with the first drab settlements of a Dutch colony in the early 17th century, perched astride a pristine, sheltered harbor at the southern tip of Manhattan island. A motley population of Europeans, mostly itinerant traders, sprang up, living often in tension with the indigenous tribes dwelling nearby. Sapokanikan, now Greenwich Village, was for a time a bustling Lenape fishing camp, but after the Europeans' arrival, its population would be muscled out. There would be friction with other aliens in New Amsterdam. In 1654, the colony's governor attempted to expel 23 Jews who had washed up on the island. They were refugees from the Brazilian port of Recife, which the Portuguese had just captured from the Dutch. His efforts ultimately proved unsuccessful, and one of the first Jewish communities in North America was established.

Dutch New Amsterdam was concentrated below present-day Chambers Street, a few blocks north of Ground Zero. The British took control in 1674 after acquiring the territory as part of a swap for a tiny Indonesian spice island. Lower Manhattan assumed its modern character in the 19th century as the first port of call for countless new arrivals from the Old World. Religious spaces became markers of the city's dizzying ethnic transformation. Sites of old Dutch Calvinist and Presbyterian congregations turned into centers for German Lutherans, then perhaps Catholics, and later become Jewish synagogues. The Lower East Side's historic Bialystoker Synagogue, founded in 1905 by immigrants from a Polish village, took over a former Methodist Episcopal church that had been built nearly a century earlier. In 1866, the Dutch Reformed Church on Henry Street became the Church of Sea and Land, a haven for sailors at port. By 1951, the building was occupied by the First Chinese Presbyterian Church, whose congregation had formed in 1910 in the heart of lower Manhattan's bustling Chinatown.

Alongside the more famous migrations of Germans, Italians, Irish and Jews came petty merchants from the fading Ottoman Empire. They comprised mostly Levantine Arabs, both Christian and Muslim, who settled in Brooklyn and along Washington Street in lower Manhattan. The latter community, said a New York Times article from 1903, "has long been known as 'Little Syria,' and those who are interested in different phases of Oriental life find much that is fascinating in this quaint section of town."

Of course, the city was not always a happy mosaic of the world, and ethnic tensions abounded, as did crime and poverty. The infamous Five Points — situated just north of today's financial district — saw routine killings, gang fights, prostitution and riots until almost the end of the 19th century. Tenements in the Lower East Side, overcrowded by slumlords and teeming with sweatshops, would spawn the modern field of urban studies, with pioneering sociologists like the Danish-born Jacob Riis profiling New York City's "other side."

Yet lower Manhattan's fabulous wealth often loomed above its squalor. Ever at the heart of American finance and business, it was there that New York City's first skyscrapers were constructed, often as futurist turn-of-the-century visions that gestured to the architecture of Mayan temples and ancient palaces. The British writer H.G. Wells approached lower Manhattan in a steamer from Liverpool in 1906 and saw in its skyline "the strangest crown that ever a city wore." In the decades that followed, the towering spires of the financial district would witness New York City's best and worst times — great rituals of triumph down Broadway's "canyon of heroes," from World Series parades to the celebration of military victories, as well as the Wall Street crash of 1929, the "Black Tuesday" that plunged the U.S. into the Great Depression.

Modern terrorism first hit the area in 1975, when Puerto Rican nationalists detonated a bomb at Fraunces Tavern, an 18th century red brick pile where George Washington bade farewell to his officers at the end of the Revolutionary War. Four were killed and dozens of others injured. In 1993, six perished when a group of Islamic radicals set off a truck bomb at the World Trade Center. The attack was only a shadow of the destruction wrought on 9/11, but it first raised the specter of Islamist terrorism over the U.S. Yet all the while, many Muslims lived, worked and prayed in lower Manhattan. The Masjid Manhattan, frequented now particularly by cab drivers and other West African and South Asian immigrants, has been in operation in a small space on Warren Street since 1970. Only months after the congregation first met, the finishing touches were applied to the Twin Towers, just four blocks away.

Correction: The original version of this story said the 1993 World Trade Center bombing was perpetrated by a group of Islamic radicals who were mainly Pakistanis. The group was mainly Arabs.