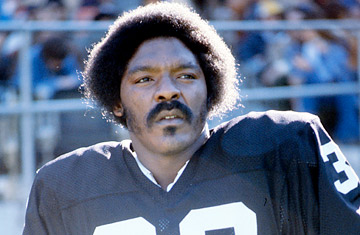

Jack Tatum of the Oakland Raiders watches from the sidelines in 1977

Last September, in the waning seconds of a football game against Illinois, Ohio State safety Kurt Coleman ran at a quarterback who was already being pulled to the ground, lowered his head and delivered a vicious helmet-to-helmet hit. The astonishing thing was that the NCAA referees, who for decades had all but ignored that kind of on-field stupidity, threw a flag. Even more stunning — and laudable — was the NCAA's decision to suspend Coleman for one game.

The Coleman incident was an unfortunate reminder that each week during football season, Ohio State coaches give an award for the hardest hit — which is fine, except that they've named it after former Ohio State player Jack Tatum. Yes, that Jack Tatum, who as an NFL safety for the Oakland Raiders paralyzed New England Patriots receiver Darryl Stingley with a barbaric helmet-to-helmet hit in 1978. It was the worst of a gallery of similar blows Tatum dished out during his violent 10-year career, earning him the macho-moronic nickname "the Assassin." In his 1980 book — which just two years after leaving Stingley a quadriplegic he was tasteless enough to title They Call Me Assassin — Tatum wrote that he liked to think his hits "border on felonious assault."

Tatum died on Tuesday in Oakland, Calif., at the age of 61, an amputee after losing a leg to diabetes in his later years. True to form, he never apologized to Stingley, who died three years ago at age 55. But it's hard to blame Tatum for thinking his "felonious assaults" weren't just permissible but actually admirable. Until just recently, we as a nation of football fans, like drunk Romans braying in the Colosseum, had regularly celebrated hits like Tatum's as the apotheosis of the game. "All Jacked Up!" to quote the sophomoric ESPN mantra — football not as skilled autumn spectacle but as brute gangsta mayhem.

Fortunately, the NFL and the NCAA — facing mounting medical evidence that the helmet-to-helmet collisions promoted by football's jacked-up culture are leading to more and more serious concussions and their lifelong consequences — are beginning to crack down. So it's fitting that Tatum passed away on the eve of a new football season: as fans reflect on his controversial legacy, we've got to ponder our Neanderthal approach to this game and start booing its excesses more loudly. And as much as I applaud any new resolve at the college and professional levels, it's even more important to fix this at the youth level — starting with the August workouts that kids like my son start next week.

Ever since I was a kid myself, I've loved the physical contact of football as much as any fan does. It's a great sport precisely because it's a healthy marriage of our yin and yang, the elegance of chess with the rawness of wrestling. But we've lost sight of what sets football's aggression apart from felonious assault. It's easy to use your helmet to spear another player in the head; it's also pathetic. Just as football prizes a gifted passer or runner, it's supposed to reward the skillful hit — your head up and to the side of an opponent with your legs driving your shoulder into his torso and, in the case of a tackle, your arms wrapped around him.

Yet too often today, you see kids in Pop Warner and high school programs — especially those playing safety, Tatum's position — wanting to make the criminal hit, the "All Jacked Up!" highlight-reel smash that they think will get them noticed by recruiters. And what's worse, especially in football-inebriated cities like Miami, where I live, some coaches encourage it, even though the players who do the spearing are just as likely to be seriously injured as their targets are. The truth, however, is that in the end it's usually loser football. When I was a high school quarterback, the defenders we feared the most weren't the "assassins" but the guys who knew strategy — the cornerbacks who could shift into a different coverage just as I took the snap and mess up every read I'd made at the line.

Yes, they also hit hard. They also hit clean, which means they usually hit sure — they didn't miss tackles trying to look like sword-swinging pirates. Or like Jack Tatum. It's good to remind youth-football players this week that one of Tatum's other famous plays resulted in his team getting knocked out of the playoffs in 1972. Instead of safely knocking down a desperation pass from Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw, Tatum went for a punishing hit on the receiver and knocked the ball into the air — where it was scooped up by Steelers running back Franco Harris, who carried it in for the winning touchdown in the final seconds, a play known as the Immaculate Reception. Raiders fans weren't calling Tatum assassin then; they were just calling him ass.

And so should all of us be called if we don't stop worshipping the gridiron goons the way we have for the past half century. This isn't just a new season; it's a new decade of a new century, and we ought to be better than this by now when it comes to our new national pastime. If nothing else, just remember that if your son is playing safety this fall, like Jack Tatum, someone else's son is playing receiver. Like my son in high school. Like my nephew in college. Like Darryl Stingley.