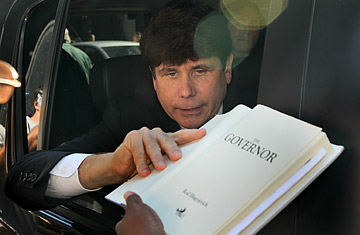

Former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich signs a copy of his 2009 book, The Governor, as he leaves court on July 26, 2010

(2 of 2)

At one point, Adam went off on a tangent and railed at the top of his lungs a story about an Italian grandmother whose mule keeps stumbling while pulling a cart. "Thattsa one! Thattsa two! Thattsa three!" Adam bellowed. The grandmother then shoots the mule dead after its third misstep, to which her husband says, "Thattsa stupid. " The old woman replies, "Thattsa one." It was a metaphor, Adam said, for the government's case. The courtroom erupted into laughter, prompting Assistant U.S. Attorney Reid Schar to stand up and tell Judge James Zagel, "This is totally inappropriate."

Zagel tried to restore order in the courtroom and reminded Adam not to turn the trial into a circus. Schar objected every few minutes, for a total of more than 20 times, challenging with a hoarse voice what he said were constant misstatement of fact by Adam. Zagel agreed almost always with Schar.

When the prosecution came up for its final argument, Schar shot down Adam's contentions by saying that Blagojevich surrounded himself with policy people who also had legal degrees — not with lawyers. And he reminded the jury that Blagojevich, too, was a lawyer. "This guy had more training in criminal background than the average lawyer. Somehow he is the accidentally corrupt governor? I mean, come on. Come on," Schar said to the jury, trying to elevate his raspy voice with sips of water. "He is the decisionmaker. He is the governor. He is the one who makes the ultimate decision." He summed up the defense's argument with incredulity: "It's everyone's fault but the defendant. That is not how it works. It is no one's job to stop him from committing these crimes. It is his job."

And, said Schar, "talking is more than enough to commit a crime ... even if, say, a person only talks about robbing a bank but doesn't actually rob it. Legally, it's called a step in furtherance, something that furthers the potential act of a conspiracy crime."

"He's not stupid," said Schar, citing Blagojevich's personal and political problems as motives for the alleged crimes. "He's very smart. He didn't get twice elected as governor for the state of Illinois by accident. He knows how to talk in 30-second sound bites. He's good at it. He does that for a living because he's a professional communicator. He knows how to tie the two together. He knows how to communicate without making it too blatant."

Accountability for action, Schar told the jury, "is the first lesson we teach our kids." At this point, Blagojevich zeroed in on Schar, elbows on the table, his hands up in prayer fashion, a triangle in front of his face. But the moment was Schar's: "We are responsible for our own actions ... The evidence in this case has proven both these defendants guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. We ask that you provide a guilty verdict on all counts. The time for accountability for these defendants is now."

The day was punctuated by tears. Midway through the session, Blagojevich's daughter Amy, 14, asked her mother Patti why such things were being said about her father, and rushed into Patti's arms for a hug during a break. She was later escorted out of the courtroom by her aunt Deb Mell, an Illinois state representative. Patti herself was in tears moments after the session ended, sobbing in the arms of her sister-in-law, much like her daughter had done just hours earlier. A few minutes later, the former governor kissed his wife's cheek. They made their way out of the courtroom, and Blagojevich began shaking hands with the spectators. One of them, Diane Phillips, shouted out, "Good luck, your honor," as he neared an elevator. With a knowing look, Blagojevich said to her, "I hope you have an extra prayer for us."

Judge Zagel is expected to charge the jury on Wednesday.