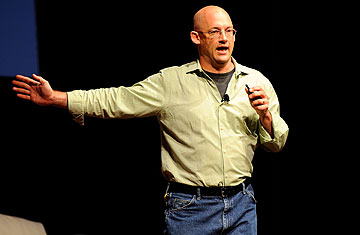

Clay Shirky attends the Wired business conference in partnership with MDC Partners at The Morgan Library & Museum on June 14, 2010 in New York City

When Clay Shirky speaks—at TED conferences, on Twitter, at NYU, where he focuses on the nexus of Internet and society—people listen. The author of the influential Here Comes Everybody is again driving conversation with his new book, Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age. Arguing that our collective free time is a resource—a "cognitive surplus"—that can be harnessed via the Internet, Shirky paints a positive picture of all the activity happening online. He talks to TIME about websites that are changing the world, the upside of narcissism, and how close he came to shutting down his Facebook account.

How can we ensure we'll use our cognitive surplus, on balance, for good?

The "on balance" question is really the complicated one. As we've seen with any democratizing medium, we always get a lot of dreck. When the printing press came along, we got erotic novels first crack out of the box; it took 150 years to get scientific journals.

The first thing we should be doing is talking to all members of society about the possibilities of participation. And the second is analogous to what went on with the invention of the scientific journal, which is to set some cultural norms around uses of the technology that are really about civic good. We'll never get to a world where the high-minded civic stuff is the majority of the medium, anymore than books are like that. But we need things like PickUpPal and PatientsLikeMe, services that are saying we could actually harness this medium not just for self-amusement, but to change the world for the better.

How do we set those cultural norms?

It's really about the kind of opportunities we shape for each other that encourage or change the way we participate. Wikis were invented in the middle of the 90s; they'd been around for five years when the Wikipedia project got started. Wikipedia happened because a small number of people decided to create an opportunity to contribute in that way for a much larger group of people. The kinds of opportunities we create for each other—in particular that small imaginative groups create for the rest of us—is going to be the thing that shapes how the medium unfolds.

Of all the projects you mention in the book—Wikipedia, PatientsLikeMe, Ushahidi [which enable grassroots civic action], PickUpPal [a carpooling site]—which were you most surprised by?

There's two. Ushahidi surprised me because it started in Kenya and has spread worldwide to become the kind of default tool for crisis-mapping in less than three years. That is a new pattern of global technology development.

The other one is PatientsLikeMe. Medical communities have been around since the dawn of mailing lists, but PatientsLikeMe is not just trying to help the members. They're actually trying to help change medical culture in the direction of more disclosure and more sharing of information, which is a big change relative to current norms of healthcare privacy. It is so socially audacious.

In those examples, you can see why sharing is beneficial. But is sharing always a good thing? Blog posts, for example, often seem to be an outpouring of narcissism...

My response to all the complaints about over-sharing and "I don't care that you're eating tasty arugula, why are you saying this on Twitter?" has always been: compared to what? When it's compared to not being able to say anything in public?

On an individual level, don't we need what we might call some passive time—just time to watch—before we jump in, comment and make a contribution?

Handwringing about whether or not we're successfully being couch potatoes— that's not a thing that keeps me up at night. If we had a world of nearly 100% consumption, and now more people are producing and sharing, people immediately extrapolate to a world of zero percent consumption and 100% producing, which of course would be everyone shouting and no one listening. But there's no danger of that. The structuring of the media environment—so that the professionals do all the producing and the amateurs do all the consuming—has shifted, but it's certainly not shifted in the direction of a total reversal or even a 50-50 split.

So there's still a divide between amateur and professional in media?

There's not a divide anymore. What had previously been a gulf is now a spectrum. We're not in a world where there's no such thing as quality. It's not the erasure of the difference between good and bad or amateur and professional; it's the fact that the clear dividing line between those two categories has instead been smoothed into a spectrum and you can find points all the way along it.

I have to admit, I've refused to join Facebook for years. Must I give in? Is it a lost cause?

I'm afraid so. I came within one button click last fall of deleting my Facebook account. I didn't do it, because there's enough urls floating around that I want to look at that people have just unthinkingly put behind a Facebook firewall. And Facebook Connect, for better or worse, has become the identity commons of the networks. Although I stopped answering friend requests years ago and have not updated a thing—I don't use the service in any of the ways that it has been meant to be used—I still have to maintain a Facebook account. I do think you're kind of doomed—

That's what my friends say.

It's practically a utility. Your friends want you there because they want to talk to you and they want you to talk back to them. That you're not doomed to do. But you are doomed to have a Facebook account, because at half a billion and counting, just as a part of the basic plumbing of daily life online, it's becoming almost essential.