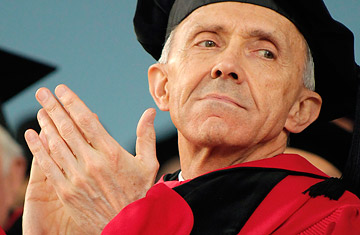

Former Supreme Court Justice David Souter attends Harvard University's 359th commencement, during which he received an honorary degree

"Judicial activism" is the No. 1 conservative talking point on the law these days. Liberal judges, the argument goes, make law, while conservative judges simply apply the law as it is written.

It's a phony claim. Conservative jurists are every bit as activist as liberal ones. But the critique is also wrong as an approach to the law. In fact, judges always have to interpret vague clauses and apply them to current facts — it's what judging is all about.

That point was eloquently made by retired Supreme Court Justice David Souter during a speech at Harvard University's 359th commencement last month.

To hear conservatives tell it, America has long been under attack by liberal judges who use vague constitutional clauses to impose their views. This criticism took off in the 1950s and '60s, when federal judges were an important driving force in dismantling racial segregation.

Conservatives say that courts should defer to the decisions made by Congress, the President and state and local officials — the democratically elected parts of government. When they interpret the Constitution, they should apply the plain words and original intent of the framers. If they do, conservatives insist, the right result will be obvious.

In his address at Harvard, Souter explained why this cardboard account of the judge's role "has only a tenuous connection to reality."

It is rarely the case, Souter pointed out, that a constitutional claim can be resolved by mechanically applying a rule. It's not impossible: if a 21-year-old tried to run for the Senate, a judge could simply invoke the constitutional requirement that a Senator must be at least 30. But many constitutional guarantees, like the rights of due process and equal protection, were deliberately written to be open-ended and in need of interpretation.

Another problem with the mechanistic approach is that the Constitution contains many rights and duties that are in tension with one another. In 1971, the court considered the Pentagon Papers case, in which the government tried to block the New York Times and the Washington Post from printing classified documents about the Vietnam War. The court didn't have one principle to apply — it had two. The First Amendment argued for allowing publication, while national security weighed against it.

The Supreme Court, rightly, came out on the side of the newspapers. But it struck many people as a difficult case to decide. As Souter noted, "a lot of hard cases are hard because the Constitution gives no simple rule of decision for cases in which one of the values is truly at odds with another."

Conservatives like to make judging sound easy and uncomplicated. At his confirmation hearings, Chief Justice John Roberts said he would act as an "umpire," applying the rules rather than making them, remembering that "it's my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat."

It was a promise that did not last long past the Senate's vote to confirm him. Roberts and the rest of the court's five-member conservative majority have overturned congressional laws and second-guessed local elected officials as aggressively as any liberal judges. And they have been just as quick to rely on vague constitutional clauses.

In a 2007 case, the conservative majority overturned voluntary racial integration programs in Seattle and Louisville, Ky. Good idea or bad, the programs were adopted by local officials who had to answer to voters. But the conservative Justices had no problem invoking the vague words of the Equal Protection Clause to strike them down.

Earlier this year, in the Citizens United campaign-finance case, the court's conservatives struck down a federal law that prohibited corporations from spending on federal elections. Once again, they relied on a vaguely worded constitutional guarantee.

In the process, they flouted the will of the people. After the ruling, a poll found that 80% of Americans opposed the ruling — 65% "strongly." The decision was as anti-democratic as any liberal ruling that conservatives have ever complained about.

A few years ago, a law professor at the University of Kentucky methodically examined the votes of the Justices, applying objective standards. She found that the court's conservatives were at least as activist as the liberals.

When Elena Kagan's confirmation hearings begin later this month, there are likely to be more charges that she would be a judicial activist. Souter's Harvard address was a timely reminder of how meaningless such accusations really are.

Cohen, a lawyer, is a former TIME writer and a former member of the New York Times editorial board.