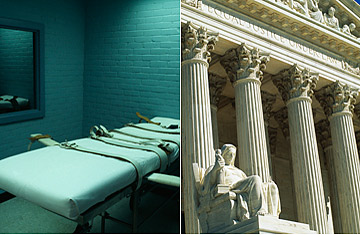

The lethal-injection room at Huntsville Prison, Texas, and the Supreme Court Building where the Hank Skinner case will be heard

Hank Skinner, who is on death row in Texas, had a simple request. Before the state took his life, he wanted to test DNA evidence from the crime scene that could prove he was wrongly convicted. Texas prosecutors, whose love for the death penalty is legendary, refused.

Skinner then sued, claiming that federal civil rights laws gave him a constitutional right to do the testing. A federal appeals court ruled against him.

On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear Skinner's case. That's good news. The Justices should use the case to expand the right to do DNA testing. But Skinner's case also gives the court a chance to confront a disturbing aspect of the nation's approach to the death penalty: the fact that the legal system does not always seem to care whether the people it executes are actually guilty.

There's no denying the crime Skinner, now 48, was convicted of in 1995 was a vicious one. Skinner's girlfriend and her two mentally challenged sons were stabbed, strangled and bludgeoned to death. But Skinner has always insisted he is innocent. The evidence against him is largely circumstantial, and his lawyers argue that the girlfriend's uncle, who they say had been harassing her that night and acted suspiciously after the crime, was likely the real murderer.

When students from Northwestern University's Medill Innocence Project investigated, they found evidence that raised serious questions about the prosecution's case. A toxicologist who testified for the defense said he had "never known a verdict of the jury to be so at variance with what I believe to be scientific fact."

It's not hard to believe Skinner could have been wrongly convicted. With the rise of DNA evidence, we now know that people are falsely convicted of crimes, including capital crimes, all too often. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, 138 people have been released from death row since 1973 with evidence of innocence.

Skinner has tried for 10 years to get access to key pieces of biological evidence — including his girlfriend's rape kit and two knives that may have been used in the killings. After prosecutors turned him down, Skinner sued, arguing that the refusal violated due process and constituted cruel and unusual punishment.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, one of the most conservative courts in the country, rejected his claim in a brief decision. The judges focused on legal fine points without engaging the larger injustice of the situation — that Texas was seeking to execute a man while denying him access to evidence that could exonerate him.

Skinner's case never should have gotten this far. When someone facing the death penalty asks for relevant evidence for DNA testing, the state's answer should simply be yes. After all, the government's interest is not in seeing people put to death or in reflexively defending criminal convictions. It is in making sure that the guilty are punished and the innocent go free.

Prosecutors do not always see it that way. They defend all sorts of practices that call into question the reliability of the convictions they obtain. A while back, in an infamous case, Texas fought to execute an inmate even though his lawyer slept at his trial — repeatedly, and for long stretches of time. The Fifth Circuit ultimately ruled that the defendant was entitled to a new trial.

This callousness about death-penalty cases is not limited to states like Texas — or to prosecutors.

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia set off a firestorm last summer when he wrote a dissent — joined by Justice Clarence Thomas — that the highest court in the land is not necessarily concerned with whether a person facing execution had actually committed the crime. The court "has never held," Justice Scalia wrote, "that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a ... court that he is 'actually innocent.'" Scalia was taking issue with the court's ruling that a lower court give Georgia death-row inmate Troy Davis a new hearing.

This idea that the Constitution allows innocent people to be put to death should be abhorrent to anyone who cares about justice. As Harvard Law School professor Alan Dershowitz pointed out, Justice Scalia seemed to be saying that if a man was convicted of murdering his wife and then showed up in court with the wife, who was still alive, seeking a new trial, it should not matter. As long as the man's conviction was procedurally proper, Justice Scalia apparently believes, he should still be executed.

The Supreme Court — which will take up Skinner's case in its next term — should rule that people accused of capital crimes can use federal civil rights laws to obtain the DNA evidence they need to prove their innocence.

And the Justices should use the case to underscore that we, as a nation, care whether people facing the death penalty have actually committed the crimes they were accused of.

— Cohen, a lawyer, is a former TIME writer and a former member of the New York Times editorial board