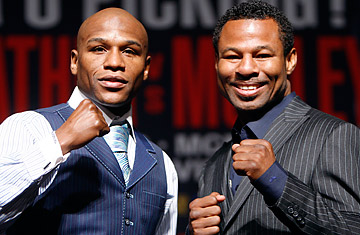

Floyd Mayweather Jr., left, and Shane Mosley pose for photos during a news conference Wednesday, April 28, 2010, in Las Vegas. The two boxers are scheduled to fight Saturday for Mosley's WBA welterweight title.

Go ahead, call it the "I Really Wish This Was The Pacquiao-Mayweather Fight, Part 2." On Saturday night in Las Vegas, Floyd Mayweather, still pound-for-pound the best fighter in America with a career record of 40-0 and 25 knockouts, will square off against "Sugar" Shane Mosley, 46-5, 39 KOs. A welterweight mega-fight, indeed, but after Mayweather and the man regarded as the best boxer on the planet, Manny Pacquiao of the Philippines, came tantalizingly close to staging the fight the world has waited for, it can't help but feel like a letdown; the talks for that bout broke down in late December after Mayweather demanded that Pacquiao undergo rigorous, Olympic-level blood testing for performance enhancing drugs, and Pacquiao refused, fearing it would weaken him before the fight. Since their fight fizzled, Pacquiao pummeled Joshua Clottey on March 13 in Dallas, the first chapter of the fights boxing fans wish were the real deal, and now Mayweather will fight Mosley.

Mayweather-Mosley, however, could end up being an influential fight in its own right — and ironically enough, it's because of enhanced drug testing. For the first time, two boxers have agreed to subject themselves to blood tests that can detect HGH, the performance-enhancing substance that remains undetectable in the basic urine testing used by state boxing commissions, as well as the major U.S. professional sports leagues. It's fair to wonder if Mayweather is posturing by suddenly demanding blood tests once he's about to fight Pacquiao, the Filipino phenom who threatens his unblemished record. And Mosley, who admitted to unknowingly taking steroids back in 2003, is trying to clear his name. But the bottom line is that this fight has set a precedent for fair play in a sport, and sports world, that badly needs it.

As of the Thursday evening before the bout, the boxers had been tested about 15 times between them; by subjecting themselves to the needle, they've come closer than any major non-Olympic athlete in this country to assuring fans, who will have to pay $54.94 to watch the fight on HBO pay-per-view, that the competition is truly clean. "This is significant," says Travis Tygart, CEO of the United States Anti-Doping Committee. "Hopefully this encourages others to do the same thing, and creates a groundswell movement for blood-testing in sports."

Will that ever happen? Within boxing, a sport where an uneven playing field can have dire consequences — it's one thing for a juiced-up jock to crush a ball with a bat, it's quite another for him to smash an opponent's skull — the Mayweather bout is creating some momentum. Tygart says that several state commissions have approached him about implementing Olympic drug testing. The New York State Athletic Commission has promised to improve its testing. In the heavyweight division, Russian title contender Alexander Povetkin has demanded that both he and champ Vladimir Klitschko submit blood to the World Anti-Doping Agency, the top performance-enhancing drug cops on the planet.

"Promoters who represent clean fighters are going to push this," says Marc Ganis, president of SportsCorp, a consulting firm. "They are not going to want to be at a chemically-induced disadvantage." A German television network even agreed to extend a deal with a promoter only if its fighters submitted to random blood tests.

The anti-doping initiative has Mayweather's camp thumping its chest. "Floyd Mayweather transcends his sport in so many ways," says Leonard Ellerbe, the fighter's manager. "The fact that he's leading by example speaks volumes." But just because Mayweather appeared on Dancing With The Stars in 2007 doesn't mean athletes across all sports will suddenly embrace blood testing, which, the argument often goes, is too invasive and expensive a procedure. Major league players, for example, will likely resist such a measure once the current labor contract expires in 2011, or at least use it as a crucial bargaining chip in negotiations with owners. "Boxing doesn't have anywhere near the clout to influence other sports in America, and around the world," says Ganis. "It's silly to think that boxing will be able to accomplish what the international anti-doping authorities has yet to be able to."

So at the very least, the Mayweather-Mosley bout could pressure Pacquiao into accepting the stricter testing terms Mayweather has demanded. And then the series of "I Really Wish This Was Mayweather-Pacquiao" fights could finally come to an end.