Bill Clinton is known for having a silver tongue. But he also has an extraordinary ear. In a speech on Friday and subsequent television interviews over the weekend, the former President fluidly connected the dots between the heated rhetoric he heard during his first years in office leading up to the bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building 15 years ago and the angry language that lately has infused the country's political debate. There are distinct differences in the discourse of past and present, to be sure, but Clinton is clearly concerned about the similarities.

Clinton well remembers the toxic environment pervading the country and the shocking violence at Waco and Ruby Ridge that preceded the horror of April 19, 1995, when Timothy McVeigh killed 168 innocent men, women and children in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. There was, Clinton has reminded us, rampant social unrest at the conclusion of the Cold War, questions about America's economic place in the world, gang violence, rising immigration problems and a plethora of societal pathologies. As a new young President, charismatic and complicated, he himself sparked a manic loathing from some fringe groups on the right that spread into a revulsion for the government as a whole. These sentiments were further inflamed by the dark drama and federal role surrounding the deaths of David Koresh and his followers at Waco, and the violence involving Randy Weaver and his companions at Ruby Ridge.

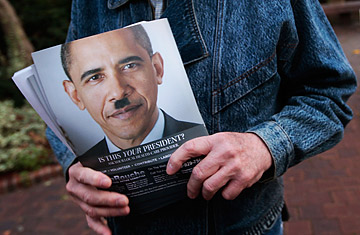

The atmosphere today may be less poisonous by some measures, but it still should cause grave concern. The combination of the nation's severe joblessness, an incumbent President who has, in some ways, become more polarizing than his two predecessors, "an enormous psychological disorientation" (in Clinton's words), and a new-media age that spreads the most inflammatory language wider and faster than before, has set off a new round of alarm bells.

Waco and the McVeigh bombing may have been instigated by sociopaths and madmen, but they nevertheless served as a manifestation of the rising polarization that turned healthy political debates first into violent talk and then into violent behavior. Except for a brief moment of unity after the terrorist acts of Sept. 11, 2001, these trends have continued to spread unabated across the country, even if they haven't yet led to actual mass violence.

Clinton's famously hardy optimism has always led him to believe that the blood sport of Beltway politics — and the 24/7 media coverage it now excites — masks a more centrist and less destructive outlook for the vast majority of American people. But many liberals, and some analysts, disagree. In their minds, a mass loop of antipathy and anti-Washington vitriol, from extremist talk radio to abrasive commentary on Fox News to Tea Party bluster to reckless Republican activists and politicians, has created an environment ripe for the creation of another McVeigh. Conservatives point out that there are comparable dangers coming from the left-wing websites that dash off casual threats of brutality and display unchecked disdain and enmity for their fellow citizens.

Meanwhile, the media has focused obsessively on the new wave of white-hot rhetoric and vicious political clashes, and sophisticated political strategists in both parties — the 42nd President included — are privately assessing the electoral implications of such fevered and concentrated press coverage. Some of President Obama's advisers consider this a plus for their side, since it helps define the Republican Party's brand with the most outrageous conservative voices and puts GOP officeholders on the spot. That same dynamic and press focus helped rescue Clinton's chances for a second term, allowing him to claim the political center.

Back in 1995, though, it was the response of the people of Oklahoma after the bombing that healed the wound and reset the tone for a time. The world witnessed moving and remarkable individual acts of heroism in the wake of the disaster. Survivors faced the grief and horror of an unthinkable attack and, like the people of New York City six years later, responded with courage, faith and a belief that America can ably withstand the assaults of terrorists, whether homegrown or foreign. In addition, Clinton, a Democratic President, worked closely with Frank Keating, Oklahoma's conservative Republican governor, to present a united team of public leadership and human compassion. "There was," as Clinton said at an anniversary event this past Friday, "this sense that this is something we had to do together and that's exactly what happened ... We didn't stop our political fights. Everything didn't turn into sweetness and light ... [But] it changed something in us. We sort of got over the idea that our differences justified our demonization of one another."

Despite all the rhetoric about red and blue states and the partisan conflicts that play out in our media every day, the American people, amid the chaos of April 19, 1995, and Sept. 11, 2001, reacted but did not overreact. The country adjusted the level of security at public buildings and airports and tolerated an expanded federal role in protecting the homeland. At the same time, the cherished freedoms of America were celebrated and valued more than ever, with vigorous debate continuing without restriction, especially in the electronic town square.

Free speech is indeed a glorious thing, but too often these days it is sullied by excessively crude and threatening invective. On this important anniversary, partisans should take a break from pointing fingers across the aisle and look into their own hearts (and on their blogs). Elected officials should reconsider the words they choose to define their opponents. Journalists should reevaluate what content is actually in the highest public interest. And we should all remember, at a time when hostility toward government is running high, that our security at home and abroad is maintained in large part by federal employees who put their own lives on the line.

"What we learned from Oklahoma City," Clinton said, "is not that we should gag each other or that we should reduce our passion for the positions we hold. [But] the words we use do matter."