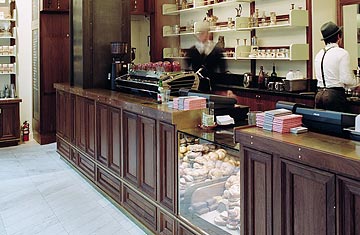

Stumptown Coffee Roasters in New York City

Coffee aficionados have been asking the question over and over again: Is Stumptown Coffee Roasters of Portland, Ore. — the most conspicuous exponent of coffee's "third wave" — the new Starbucks?

Wait, you haven't heard of the third wave? Get with the program! In cities across America, a fervid generation of caffeine evangelists are changing the way we drink coffee. They tend to be male, heavily bearded, zealous and meticulous in what they do. And the coffee they produce is as much an improvement over Starbucks and its rivals as Starbucks was over Taster's Choice. Stumptown didn't make a movement by itself. There's Intelligentsia in Chicago and Counter Culture in North Carolina, and as far back as the 1980s, some roasters, like David Dallis of Dallis Coffee, were seeking to import beans from single farms, roasting them less rather than more and generally doing the things that separate this movement from its Seattle-based progenitors in the '70s.

But according to Oliver Strand of the New York Times, who has covered the third wave as well as any writer in America, "Stumptown is the leader. They're the cutting edge." The company, which recently opened a plant in Brooklyn, routinely pays more at auction for prized lots of coffee beans than anyone else, offers more single-origin coffees than anyone (20 at the New York plant) and is at the forefront of nearly every new-coffee frontier: espresso-delivery technology, international partnerships and generally changing the idea of coffee from a staple commodity, like corn or sugar, to something closer to wine, with seasons and terroir and varietals as different as Burgundy chardonnay and Austrian riesling. But most of all, Stumptown has Duane Sorenson, its charismatic founder and the most visible (and polarizing) figure in contemporary coffee.

To Sorenson, his zeal (he comes from a Pentecostal family) is what made Stumptown what it is. "We started Stumptown with the idea of getting to the source," he says. "That was the concept, and that excitement is what we wanted to bring to our customers." Every Stumptown bag has a card in it that describes the elevation, location, varietal and tasting notes of the beans it contains. Then you turn it over and there's a profile of the area as well as technical information ("In addition to improved cherry selection and a return to double fermentation, à la the Kenyan style, we've now installed a pre-drying stage ..."). Yes, this is coffee for coffee geeks, but the same could have been said about cheese and wine and meat 20 years ago. And you can have a Stumptown or like-minded artisanal coffee for $2, way less than a Venti Mocha Latte. (Stumptown also offers espresso drinks such as cappuccinos, macchiatos, etc.) Which brings us back to Starbucks.

What all the third wave coffee people have in common is a thinly veiled revulsion at Starbucks and its rivals, in particular the way they overroast their beans. "Coffee beans aren't supposed to be uniformly dark and shiny," says John Moore of Dallis. "Every bean has a level it's supposed to be roasted to, so that you can taste it. Otherwise it's like cooking all meat well done."

Sorenson, despite being famous for his dismissal of coffee infidels, takes a more diplomatic tack: "Starbucks laid the path. They made people aware. They offered better coffee in their time than was out there. But now there's far more specialty coffee out there today, and there will be even more so five years from now that will give the consumer — Midwest, West Coast, East Coast, wherever — a lot more options than Starbucks."

But not yet. There aren't any third wave options when you're at the mall or the Exit 17 service plaza or your office or ... almost anywhere. In fact, the most obvious thing about Starbucks is its omnipresence. Intelligentsia sells via mail order. Counter Culture has stores, and even training centers, in Asheville, Charlotte and Durham, N.C.; Atlanta; New York City; and Washington, D.C. But there's just no way any farm-to-cup roaster can open up 60 stores, let alone 16,000-plus like Starbucks. But every town can have a café that, if it doesn't buy its coffee beans from a small farm in Burundi or Costa Rica, at least can buy them from someone who does. According to an industry trade publication, what is loosely called "specialty coffee" accounts for $13.65 billion in sales, one-third of the $40 billion that Americans annually spend on coffee. Obviously, only a small fraction of that is from third wave coffee. But how big was the specialty sector when Starbucks got the ball rolling in the 1970s?

For Sorenson, it's all about the willingness of Americans to pay a little more. "The first day we opened [in 1999], we weren't in the position to pay what we do for a pound of coffee. But within a few years, people tasting our coffee experienced it as they never had." And, as Strand points out, "even when it costs more, you're still talking about getting an incredible experience for $2."

That's the logic, of course, which led to the $5 latte, which probably seemed equally outlandish when coffee was 50 cents a cup at most diners. But you don't have to take Duane Sorenson's word for it, or mine, or anybody else's. Try this kind of coffee, and soon. Even if, like me, you're a brute who puts evaporated milk and Sweet'n Low into it, you'll find that your days will start better drinking coffee of this caliber, and not just because of the caffeine.

Who knows? You may even feel like growing a beard and opening a roasting plant of your own.

Josh Ozersky is a James Beard Award–winning food writer and the author of The Hamburger: A History. You can listen to his weekly show at the Heritage Radio Network and read his column on home cooking on Rachael Ray's website. He is currently at work on a biography of Colonel Sanders.