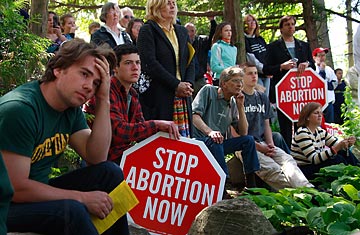

Pro-life activists protest President Barack Obama's visit to Notre Dame University in May, in South Bend, Ind.

For decades, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) has been one of the most steadfast advocates for health reform, arguing that "access to basic, quality health care is a universal human right, not a privilege." And yet on Oct. 8, a trio of leaders representing the USCCB wrote a letter to the U.S. Senate warning that they would have to "vigorously" oppose health-reform legislation unless certain changes were made. The issue most likely to stand in the way of the bishops' support is one that could have been predicted months before debate even began: abortion.

The fact that disputes over abortion coverage remain an obstacle at this point in the process — more than two dozen pro-life House Democrats have also vowed to vote against reform legislation because of it — might suggest that the White House dropped the ball. But while Obama's outreach to the USCCB has left much to be desired, the bishops deserve a fair share of the blame for the continuing stalemate. If anything, their inconsistent approach to the issue created confusion that has hampered Democratic attempts to accommodate their concerns.

As late as mid-summer, it appeared that Democrats and the bishops were on track to work out an understanding. In late July, Cardinal Justin Rigali of Philadelphia, who at the time was heading the USCCB's pro-life committee, sent a letter to members of the House Energy and Commerce Committee that appeared to signal that there was room to accommodate Catholic concerns. The USCCB, Rigali wrote, wanted health reform to continue the policy of preventing "direct federal funding of abortion." The language was important because it seemed to match an amendment drafted by Representative Lois Capps, a Democrat in California, to address pro-life concerns. Under the Capps amendment, which the Committee approved, no federal dollars could directly fund abortion procedures. An individual could obtain an abortion if her insurance plan covered it, but the procedure would be paid with segregated dollars from a pool funded by privately paid premiums.

The Democrats who helped negotiate the Capps compromise, according to one person who was involved, felt confident it would "help clear the way for the bishops to support" the House health-reform bill. But just a few weeks after Rigali's initial letter, the Cardinal on Aug. 11 sent a second letter to members of Congress that raised a new concern: "Funds paid into these plans are fungible, and federal-taxpayer funds will subsidize the operating budget and provider networks that expand access to abortion."

Rigali's argument was that allowing any insurance plan in the public exchange to provide abortion coverage — even if the abortions were paid for out of a separate pool — would constitute federal funding of abortion because some consumers would purchase those health plans using government subsidies. This fungibility argument shifted the issue from direct federal funding of abortion to indirect funding. And eliminating indirect funding of abortion is a nearly impossible standard to meet. Taxpayers already subsidize abortions through the tax break given to employers for sponsoring company-insurance plans, and technically any employer that receives a government grant — say, for laboratory research — has a fungibility issue if it uses an insurance plan that includes abortion coverage.

Democrats' reaction to Rigali's new stance has been twofold: feelings of frustration that the bishops hadn't been negotiating in good faith, and a broader confusion over where the bishops actually stood. The confusion appears to have been particularly pervasive at the White House. On Sept. 8, a few weeks after the second Rigali letter, senior Obama officials convened a meeting in the Roosevelt Room that included Nancy-Ann DeParle, the Administration's lead health-care official, Joshua DuBois, head of the White House faith-based office, and John Carr, executive director of the USCCB's Department of Justice, Peace and Human Development. Both sides characterize the encounter as cordial and felt there was room for agreement on the main Catholic priorities: providing conscience protections for health-care workers and institutions that object to abortion; guaranteeing that abortion coverage was not mandated; and preventing federal funding of abortion.

Given the fact that the meeting took place when debate over health reform was already in full swing, it's likely that the two sides were simply hearing what they wanted to hear. Whatever the case, they have certainly been talking past each other ever since. Obama added abortion funding to the list of "myths" like death panels that he dismissed in his public appearances. When he said in his address to the joint session of Congress in September that "under our plan, no federal dollars will be used to fund abortions," the President was referring to direct funding. But when Richard Doerflinger of the USCCB praised Obama, saying "We especially welcome the President's commitment to exclude federal funding of abortion," he was interpreting the statement as a pledge to insert language prohibiting indirect funding of abortion.

White House press secretary Robert Gibbs made matters worse by repeatedly answering questions about the Administration's position on the "use of federal dollars for abortion" by insisting that federal law already prohibits the practice. Gibbs was referring to the Hyde Amendment, which bans the use of federal dollars for abortions under Medicaid, with exceptions for rape and incest. But the law is only limited to Medicaid, and Gibbs' insistence that existing law prohibits direct federal funding of abortion continues to rankle many Catholics.

Democrats may still find a way to address the USCCB's concerns in health reform — and they're negotiating separately with the pro-life Democrats who will be needed to pass health-reform legislation. But some feel burned by earlier attempts at negotiation and are ready to forget about courting the bishops' support. They point out that the Catholic Health Association, which represents more than 1,200 Catholic health systems and facilities, has been more encouraging of Democratic proposals (although the CHA has yet to endorsed any bill). Obama recently appointed CHA's president and CEO, Sister Carol Keehan, to be part of the official delegation to Rome for the canonization mass for Hawaii's Father Damien.

If the Administration and congressional Democrats can't find a way to appease the USCCB — and their appetite for compromise may be limited given the sense that the standard has shifted — the bishops could find themselves openly opposing a cause they have long championed. If that happens, they will have themselves to blame as much as anyone else.