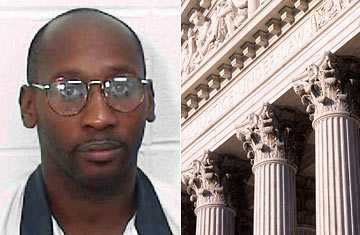

Georgia death-row prisoner Troy Davis, left

Under normal circumstances, it takes a case of national importance to rile the Supreme Court during its summer recess. But in the words of an old axiom about capital punishment, "death is different." And so, on a sleepy mid-August Monday, Aug. 17, the court — over a strong dissent — dusted off an antique tool, unused for nearly half a century, to force a new hearing into the slow-rolling fate of a Georgia death-row prisoner named Troy Davis. In the process, the court has opened up new questions about the death penalty: most crucially, how far the courts must go to ensure that an innocent person — as a wide array of politicians, former prosecutors and judges contend Davis is — is not executed.

Like most death-penalty cases, this story is maddening and convoluted. Davis was convicted in 1991 of a tawdry and pathetic 1989 murder. On a hot Savannah night almost exactly 20 years ago, Davis and two acquaintances were hassling a homeless man at a Burger King parking lot next to the bus station. They wanted his beer, and one of the bullies — either Davis or a fellow known as Red Coles — clubbed the victim with a handgun. As it happened, an off-duty police officer, Mark MacPhail, was providing security at the restaurant. When he came running to the scene, the man with the gun shot the officer to death.

Anyone who has ever spent a few weeks on the police beat could guess what happened next. Coles blamed Davis. Davis fingered Coles. Investigators built a case from the available materials: ambiguous ballistics, jailhouse snitches, witnesses with grudges and the often unreliable observations of the sort of folks who need a burger at 1 a.m. The amalgam was enough to persuade 12 jurors that Davis was guilty, and because the dead man wore a badge, the sentence was death.

Five years later, Congress, exasperated by the seemingly endless nature of death-penalty appeals, passed a law intended to speed the death-row journeys of prisoners like Davis. Optimistically called the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), the new law attempted to limit death-row prisoners to one set of appeals in federal court. Despite the restriction, Davis raised a variety of constitutional issues in his trip through the federal courts. Along the way, his lawyers accumulated a stack of affidavits from the motley crew of witnesses and from snitches of their own recanting their trial testimony and, in some cases, pointing new fingers at Coles. The Davis case became a morass of contradictory statements from addled witnesses, many of whom were either lying then or are lying now — or maybe both.

Still, a necessary fiction underpinning our justice system is the idea that juries get things right, and so over the years, the courts found no reason to overturn the verdict, in some instances rejecting Davis' appeals on purely procedural grounds. At one point, the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles conducted a detailed examination of the new evidence, but when it decided that Davis did not deserve mercy, the prisoner was forced to ask a panel of judges from the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals for special permission under the AEDPA to file a second federal appeal — this one based on the simple claim that Davis is plainly innocent.

By a vote of 2 to 1, the panel ruled against Davis, and this is where the Supreme Court comes in. Numerous times since the 1996 law was passed, the high court has ruled that the limits imposed by the AEDPA are valid — when they restrict the lower courts. But the Justices held open their own prerogative to issue a writ of habeas corpus if so moved. In other words, the lower federal courts had no power to hear another word from Davis. But he could make his pitch directly to the Supreme Court. Prisoners have been trying for nearly 50 years without success to get the Justices to employ this "original jurisdiction." Davis succeeded.

"The substantial risk of putting an innocent man to death clearly provides an adequate justification," wrote Justice John Paul Stevens, in an opinion joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer. "Simply put, the case is sufficiently 'exceptional' to warrant utilization of this Court's" power to intervene from on high. The court ordered a federal district judge in Georgia to examine all the conflicting evidence in the case and determine whether Davis is, in fact, innocent.

But that in and of itself seems to violate the AEDPA, which specifically bars the district judges from having anything more to do with this case. This wrinkle sent Justice Antonin Scalia to his writing desk. In a dissent joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, Scalia noted the odd fact that the Supreme Court was ordering the lower-court judge to hold a hearing that, according to Congress, the judge is not allowed to convene. "Without explanation and without any meaningful guidance," Scalia wrote, the court was sending the district judge "on a fool's errand." The evidence, he asserted, "has been reviewed and rejected at least three times," and even if the judge finds it compelling, where's the legal power for the judge to act?

For Douglas Berman, a law professor at Ohio State University, "the way the court 'decided' the Troy Davis case today raises a lot more questions than it answers. It also probably ensures still more litigation in the future."

Among the questions: Is the district judge advising the Supreme Court on how to handle the Davis case or is the matter now formally in the district court again? Do the three silent Justices, who signed neither opinion — Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Anthony Kennedy and Samuel Alito — have a shared view of this unusual action? (Newly sworn-in Justice Sonia Sotomayor did not participate in the case.) Is this step a prelude to an official determination that the Constitution forbids the execution of an innocent prisoner, a seemingly obvious assumption that has never been formally declared? If so, what new filters of trial procedure and judicial review will have to be installed to reach that level of certainty and perfection? In his dissent, Scalia wrote, "This court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is 'actually' innocent."

The court's August eruption highlights once again the fundamental screwiness of America's death penalty. In the marble halls of our rational humanity, we demand absolute clarity and justice. As one of the many judges who has reviewed Davis' case puts it, "I do not believe that any member of a civilized society could disagree that executing an innocent person would be an atrocious violation of our Constitution and the principles upon which it is based."

But most murders don't happen in the precincts of the rational or the just. They happen on the late-night mean streets, where truth is often a figment, and memory is as slippery as the greasy pavement.