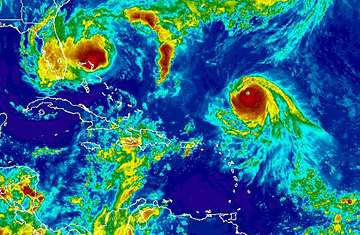

Tropical Storm Hanna passes the edge of the Bahamas as Hurricane Ike, a still-more-dangerous Category 4 storm, advances from the east.

Hurricane season is two months old and not a single named storm has popped onto the radar. If that makes people complacent, it only makes weather watchers worry even more about what is to come. Officials and insurers are concerned about the ramifications of a "Big One," and Florida, the most ravaged of states, is looking at several novel approaches to riding out the storms — or even preventing them altogether.

The most innovative is a proposal from Microsoft founder Bill Gates to redirect or shrink hurricanes by cooling the waters where they are generated. Since hurricanes gather strength over tropical waters such as the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, cooling them would weaken the storms before they made landfall. The plan calls for huge ocean-going tubs that would use waves and turbines to push down the hotter surface water while sucking up the cooler water from below.

Coastal residents — who suffer under high insurance rates — would be asked to cover the cost, according to an application filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on July 9. Gates is one of a dozen inventors listed on the application submitted by Searete LLC, a subsidiary of Intellectual Ventures LLC, of Bellevue, Washington.

Paul "Pablos" Holman, an inventor at Intellectual Ventures, says the proposal would be used only as a last resort — as a "Plan C." But many experts are skeptical of its practicality. "I have a hard time picturing doing this on the magnitude required, but it's an interesting idea," says University of Florida Professor of Geological Sciences Ellen Martin. "It may be easier to just dump a bunch of ice cubes out of an airplane, but it will take a lot of those too."

Hugh Willoughby, acknowledged as the "guru of hurricane modification" and now a professor at Florida International University, dismisses the plan as "junk science." The cost and logistics don't add up, he says, estimating that it would take tens of thousands of the giant tubs put in the water within 24 hours of the storm's arrival. Others think the whole idea of trying to dissipate hurricanes before they start is misguided. Bob Atlas, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Miami, points out that hurricanes, as devastating as they can be, do serve some good, by helping ward off droughts, and that tampering with them could have untold environmental ramifications.

If the storms can't be warded off, the state is also looking to ways of responding to them more efficiently. Florida's top emergency manager has floated a novel idea to turn the housing crash into an advantage, by using 250,000 foreclosed homes as temporary hurricane shelters. "This option didn't exist two or three years ago before the real-estate market crashed," Ruben Almaguer, interim director of Florida's emergency management division, told the Miami Herald last month following a mock-disaster drill that highlighted the shortage of hurricane shelters in the state. "We can't not look at something staring us directly in the face," Almaguer said. "It's a solution to a potential problem."

But the proposal isn't getting much support. Richard Shuster, a Miami attorney who writes the Florida Foreclosure Defense blog, notes that foreclosed properties are often uninhabitable. "Homeowners in foreclosure or thieves after foreclosure often strip homes of appliances, fixtures, air conditioners, and anything else of value, including hurricane shutters," he says. The Federal Emergency Management Agency is not considering such a measure. "Under FEMA's mission of sheltering disaster survivors, this is not an option that we would utilize," agency spokesman Clark Stevens says.

That leaves the perennial problem of evacuation. Some have proposed reexamining a solution that traffic engineers began looking into in 1990, after Hurricane Floyd prompted massive traffic jams as people in the Carolinas fled their homes. The lanes going in the opposite direction were empty. So road scholars focused on the possibility of making all lanes go in one direction, says Louisiana State University Prof. Chester Wilmont.

Florida has had a standby plan for one-way evacuations since 1994, but it has yet to make the idea a priority. Officials prefer to execute staged evacuations, first with tourists and trailer park residents and then with outlying beach communities, so that the evacuation is orderly and traffic continues to flow, says Jennifer Olson, chief operating officer of Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise.

The standing one-way plan would also require a lot of manpower: an estimated 720 more transportation workers and state troopers to police traffic in the Miami area alone, more than doubling what was required before. Worst of all, traffic would slow where the roadway narrows in Palm Beach County. "You’ll have traffic jams backed up for miles," says Metropolitan Planning Organization Director Randy Whitfield. "If you have an accident, it will totally shut down the evacuation."