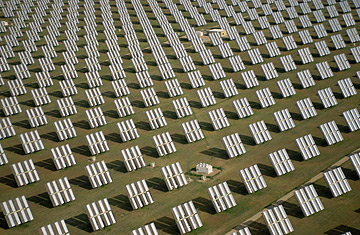

Solar panels in Carrisa Plains, California, photographed in 1987. This ARCO photovoltaic power plant was dismantled in 1995

California wants to run on sunshine. The state is forcing utility companies to provide 20% of their output by way of solar power and other forms of renewable energy by 2010. Last November, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger said he wanted the portion to be one-third by 2020. Now the feds are bringing the money to help fund all this sunny energy, with the Obama Administration's stimulus package promising to pay for 30% of solar-power projects that begin by the end of 2010.

But could this politically backed, popularly supported solar surge spiral into eco-disaster? That's what some say is happening to the Carrisa Plains, a sparsely populated swath of arid, sunny and relatively cheap land in eastern San Luis Obispo County, where three of the world's largest solar plants ever proposed are under review. Together, the Topaz Solar Farm, California Valley Solar Ranch (both photovoltaic projects) and the Carrizo Energy Solar Farm (a solar thermal operation) would provide energy to nearly 100,000 Golden State homes, but only by covering roughly 16 sq. mi. (41 sq km) of the ecologically sensitive plains with solar panels and industrial development. All three plants have deals with Pacific gas & Electric (PG&E) (which declined to comment for this story), and all want to start construction by the 2010 deadline for federal funds. And more solar-plant proposals are on the way, in large part because transmission lines with available capacity already run through the region. (See 10 next-generation green technologies.)

"It's peaceful out here. I love the wildlife," says Mike Strobridge, 32, an auto mechanic, explaining why he moved to the Carrisa Plains with his daughter. "But then these solar guys are going to come in, and they're just gonna destroy the area." Strobridge is especially troubled because he will be "surrounded on four sides" by the three projects. What's more, like his neighbors and other concerned parties — including the Environmental Center of San Luis Obispo County — Strobridge is worried about the impact the power plants will have on endangered species such as the San Joaquin kit fox. He is also concerned about the effect on dwindling water supplies as well as the more intangible treasures of the area: the unimpeded views, the stark silence, the rustic natural beauty, the huge wilderness area called the Carrizo Plain National Monument just down the valley — that is, just about everything that led him to buy the property 10 years ago. (Read a story on mapping the best solar-energy sites in the U.S.)

Robin Bell, a museum exhibit designer who built her retirement home on the plains less than half a mile from one of the proposed plants, started the Carrisa Alliance for Responsible Energy to combat the projects. Says Bell: "I personally feel strongly that all of these rules and regulations are in place for a reason and, in the name of being green, these power companies are exploiting them and taking all kinds of liberties with the environment." She says she prefers distributed solar power (by way of roof panels on individual homes) rather than via sprawling power plants and believes technology will come on board within the next few years to make that a more feasible option. "I totally support the development of renewable energy, but at what cost? This is a knee-jerk reaction to stalling global warming. But what kind of costs are we going to do to the environment?" (See where the future of renewable energy lies.)

Katherine Potter, a spokeswoman for Ausra, the company proposing the solar thermal plant, insists that large-scale solar is needed, and soon. "There is certainly a good place for distributed generation, but to ensure the reliability of the grid, you do need large-scale power generation," she says, explaining that solar thermal is the most efficient renewable energy source available in terms of the amount of land used.

But it's not just annoyed neighbors and environmental attack dogs who are worried about these solar plants. John McKenzie is a planner for the County of San Luis Obispo, which is processing the applications for the photovoltaic projects. (The solar thermal project goes through the California Energy Commission.) "There are a couple of pretty serious issues that need to be resolved," he says, pointing specifically to the biological resources, water-supply concerns and agricultural protections that have to be evaluated before the county gives the go-ahead to the applicants. How much experience does he or anyone in the county have with these kinds of processes? "Zero," says McKenzie, a 20-year county-planning employee. "These are the two biggest plants in the world ... This county is getting to be one of the first folks to deal with it." Will any of these projects make it by 2010? "There's a possibility," he says, adding that the county is "making a concerted effort to keep time frames down" but that there could be a "whole slew of stumbling blocks."

This isn't the first time solar has been proposed for the plains, however. Darrell Twisselman — whose family has lived in the area since the 1880s and whose land would host the two photovoltaic plants for a hefty profit — remembers when they built a solar photovoltaic plant there in the mid-1980s. (At 6 megawatts, it was tiny compared with the current proposals, one of which has a 177-megawatt capacity.) The project faced similar gripes then. "Everyone complained about them for two weeks, and then everyone forgot," Twisselman says. "And they were what you might say unsightly. You could see them from everywhere." The technology, however, was worse then, and "the panels cooked," melting in their own heat, says Twisselman. That was just one reason the government pulled funding and the project was dismantled.

Despite the earlier Carrisa solar experiment, the state feels it is still inexperienced in judging the impact of huge solar plants. According to California Energy Commission chairwoman Karen Douglas, "We've got much more experience siting natural-gas plants than siting renewables, both from a staff and commission perspective. So some issues are rising up in the renewables case that are substantively different than what has been the core of the siting work before the solar applications started coming in so quickly."

Schwarzenegger has asked state agencies to streamline the process with an eye on speed (and the federal deadline) as well as the environment. But this process, which included a workshop held last week, is still in the early stages and is focused mainly on the Mojave and Colorado deserts, where other future solar plants would go. As such, it remains unclear how this process will affect the Carrisa Plains, especially with the pressure building for the 2010 deadline.

Back on the plains, Strobridge is just trying to save the place he calls home. "At this point," he explains, "we're very frustrated and doing everything we can to make sure if something does come in, it's put in responsibly."