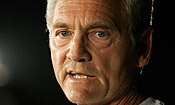

Don Siegelman

Next month in Atlanta, a federal court will hear the high-profile appeal of former Alabama governor Don E. Siegelman, whose conviction on corruption charges in 2006 became one of the most publicly debated cases to emerge from eight years of controversy at the Bush Justice Department. Now new documents highlight alleged misconduct by the Bush-appointed U.S. Attorney and other prosecutors in the case, including what appears to be extensive and unusual contact between the prosecution and the jury.

The documents, obtained by TIME, include internal prosecution e-mails given to the Justice Department and Congress by a whistle-blower during the past 18 months. John Conyers, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, which investigated the Siegelman case as part of a broader inquiry into alleged political interference in the hiring and firing of U.S. Attorneys by the Bush Justice Department, last week sent an eight-page letter to Attorney General Michael Mukasey citing the new material.

Conyers says the evidence raises "serious questions" about the U.S. Attorney in the Siegelman case, who, documents show, continued to involve herself in the politically charged prosecution long after she had publicly withdrawn to avoid an alleged conflict of interest relating to her husband, a top GOP operative and close associate of Bush adviser Karl Rove. Conyers' letter also cites evidence of numerous contacts between jurors and members of the Siegelman prosecution team that were never disclosed to the trial judge or defense counsel.

The letter to Mukasey is a signal that Democrats intend to probe what critics call the "dark side" of the Bush Administration even after it leaves office, according to congressional sources. Besides the Siegelman prosecution, such investigations could focus on the authorization of harsh interrogation methods and the role of Karl Rove and former White House aide Harriet E. Miers in the firing of U.S. Attorneys.

Siegelman was released on bail earlier this year after a federal court ruled that his appeal raises "substantial questions." But the issue that turned the case into a national controversy was the allegation of political bias. Critics, including a bipartisan group of 52 state attorneys general, have raised numerous questions, including the allegation that Siegelman was prosecuted at the insistence of Bush-appointed officials at the Justice Department and Leura G. Canary, a U.S. Attorney in Montgomery whose husband was Alabama's top Republican operative and who had worked closely with Rove for years.

When the House Judiciary Committee looked into the Siegelman affair earlier this year, the DOJ issued statements, placed in the Congressional Record, maintaining that the case had been handled only by career prosecutors, not political appointees, and that Canary had recused herself in 2002, "before any significant decisions ... were made."

But new documents furnished by DOJ staffer Tamarah T. Grimes tell a different story. A legal aide who worked in the Montgomery office that prosecuted Siegelman, Grimes first submitted her documents to DOJ watchdogs in 2007, and now finds herself in an employment dispute that could result in her dismissal. Grimes' lawyer had no comment.

The documents — whose authenticity is not in dispute — include e-mails written by Canary, long after her recusal, offering legal advice to subordinates handling the case. At the time Canary wrote the e-mails, her husband — Alabama GOP operative William J. Canary — was a vocal booster of the state's Republican governor, Bob Riley, who had defeated Siegelman for the office and against whom Siegelman was preparing to run again. Canary also received tens of thousands of dollars in fees from other political opponents of Siegelman.

In one of Leura Canary's e-mails, dated Sept. 19, 2005, she forwarded a three-page political commentary by Siegelman to senior prosecutors on the case. Canary highlighted a single passage, which, she told her subordinates, "Ya'll need to read, because he refers to a 'survey' which allegedly shows that 67% of Alabamans believe the investigation of him to be politically motivated." Canary then suggested: "Perhaps [this is] grounds not to let [Siegelman] discuss court activities in the media!"

Prosecutors in the case seem to have followed Canary's advice. A few months later they petitioned the court to prevent Siegelman from arguing that politics had any bearing on the case against him. After trial, they persuaded the judge to use Siegelman's public statements about political bias — like the one Canary had flagged in her e-mail — as grounds for increasing his prison sentence. The judge's action is now one target of next month's appeal.

"A recused United States Attorney should not be providing factual information ... to the team working on the case under recusal," Conyers wrote to Mukasey last week. Justice Department spokesman Peter Carr said only that "the department will review the letter." A spokesperson for Canary said she had nothing to add.

Beyond providing the e-mails, Grimes has given a written statement to the Department of Justice that Canary had "kept up with every detail of the [Siegelman] case." If true, Conyers told Mukasey, this raises "serious concerns" because "it is difficult to imagine the reason for a recused [U.S. Attorney] to remain so involved in the day-to-day progress of the matter under recusal."

Last year Grimes gave the DOJ additional e-mails detailing previously undisclosed contact between prosecutors and members of the Siegelman jury. In nine days of deliberation, jurors twice told the judge they were deadlocked and could not reach a decision. After the panel finally delivered a conviction, allegations emerged that jurors had discussed the case in e-mails among themselves and downloaded Internet material — serious breaches that could have invalidated the verdict. But the trial judge ruled that the jurors' alleged misconduct was harmless.

The DOJ conducted its own inquiry into some of Grimes' claims and wrote a report dismissing them as inconsequential. But the report shows that investigators did not question U.S. Marshals or jurors who had allegedly been in touch with the prosecution.

A key prosecution e-mail describes how jurors repeatedly contacted the government's legal team during the trial to express, among other things, one juror's romantic interest in a member of the prosecution team. "The jurors kept sending out messages" via U.S. Marshals, the e-mail says, identifying a particular juror as "very interested" in a person who had sat at the prosecution table in court. The same juror was later described as reaching out to members of the prosecution team for personal advice about her career and educational plans. Conyers commented that the "risk of [jury] bias ... is obvious."

What's more, when prosecutors conducted their own investigation of suspected improper conduct by jurors after the trial, two of them were interviewed, despite instructions from the judge that no contact with jurors should occur without his permission. Those interviews were not publicly disclosed until nearly two years later, when the head of the DOJ's criminal division belatedly wrote all parties, including the appeals court in Atlanta, to inform them.

Further undisclosed evidence of prosecution team members speaking with jurors following the verdict emerges in Grimes' written statement to the DOJ. In it, she says a member of the team prosecuting Siegelman had spoken with a juror suspected of improper conduct — apparently at the time the judge was due to question the juror about that conduct. Grimes quotes the lead prosecutor in the case as saying someone had "talked to her. She is just scared and afraid she is going to get in trouble."

In his letter to Mukasey, Conyers calls this additional juror contact "important information," noting, "It is startling to see such repeated instances of federal prosecutors failing to keep the defense apprised of key developments in an active criminal case." He might have added that the judge was, in some instances, apparently not in on the secret either.