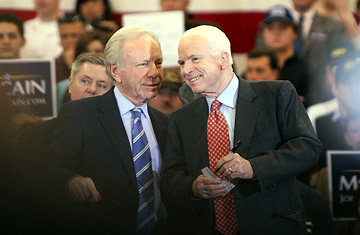

John McCain speaks with Sen. Joe Lieberman during a campaign appearance at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Joe Lieberman is having a not-so-secret affair on his political spouse of the past four decades. The Connecticut Senator — now an Independent, but until 2006 a staunch Democrat, married to the party — is not just campaigning for presumptive Republican nominee John McCain; he is, to even the most objective eye, in a deep state of rapture.

You'd think hell hath no fury like a party scorned, but Democrats aren't kicking Lieberman out of the party — yet. Lieberman has a decent claim of abandonment: after a 2006 Democratic primary challenge over his unyielding support for the war in Iraq, Lieberman won his fourth Senate term as an Independent who caucuses with Democrats. Without his good will there would be no Democratic majority in the Senate, no control of the legislative calendar, no subpoenas and investigations and no committee chairmanships. (Lieberman himself chairs the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee.) Harry Reid owes his title to Joe Lieberman. Dumping him is not an option.

Sitting in his Hart Senate Offices, just next door to Obama's suite, Lieberman claims that being forced to run as an Independent in 2006 revolutionized his political outlook. "Let's face it," he says, "the fact that I was elected an Independent liberated me.'" Liberation first manifested itself on legislative issues, like setting a time line to withdraw troops from Iraq and allowing the Bush Administration to wiretap without warrants, where he flexed the fact that he was beholden to no party. It became unmistakable as the 2008 race for the White House took shape and Lieberman openly endorsed McCain, his best friend in the Senate. "I'm going to do everything in my ability to do what I feel is right, or sensible and I'm not going to calculate what the political impact is. I must say I feel very," and here Lieberman paused, looked up and spread his hands, "free."

Still, every time the former vice presidential nominee praises John McCain and criticizes Barack Obama, steam rises from his colleagues. "I'm not going to pull my punches or hold back," says Lieberman. "To me I'm doing just what they do, maybe something less than some of them are doing because I think they've attacked John [McCain] in ways that I don't appreciate. I'm just doing what they're doing for their candidate; it happens that I'm supporting a Republican."

As long as Democrats need him to hold on to power, Lieberman realizes that comments like these make him untouchable. "Without him we would not be in the majority," says Dick Durbin, the second highest-ranking Democrat in the Senate. "He votes with us on virtually every issue except for the war and, of course, his support for Senator McCain. There is disappointment, for sure, and many people have expressed concern about his role, but he's going to have to make that decision."

Back in December 2007, when Lieberman endorsed McCain, the Arizona Senator seemed like a long shot for the nomination. "My wife teased me," says Lieberman. "She said, 'There you go getting yourself into trouble again, but I guess the reassuring thing is the McCain campaign is going to be over soon so you won't have to carry on.'" Now Lieberman is raising money and campaigning for the presumptive nominee, and has said he would even speak at the Republican National Convention if asked. (He would not, however, accept a vice presidential nomination or a cabinet position.) "I've made a full-hearted decision here — with my heart and my head," Lieberman says. "I really believe in McCain."

If that belief remained tacit, Democrats wouldn't quite be so peeved. But in March, Lieberman told ABC's This Week that the Democratic Party has "been effectively taken over by a small group on the left of the party that is protectionist, isolationist and hyper-partisan." And earlier this month Lieberman participated in a G.O.P.-sponsored conference call criticizing Obama's speech before the American Israel Political Affairs Committee, a leading Jewish Organization.

Lieberman insists he's simply highlighting differences between the two candidates' records, and he would never make personal attacks. Still, he didn't exactly demur when asked to compare McCain and Obama's records in reaching across the aisle. "If you compare [McCain's] record to Senator Obama's, it's not just that Senator Obama has only been in the Senate for only three and a half years and McCain's been here 21 years," Lieberman huffed. "Senator Obama has done very little of that in his time here, very little bipartisan work."

What Lieberman considers drawing distinctions, his peers consider unseemly. "I think people see a difference between supporting someone who's your colleague and friend and attacking the nominee of the other party," says Senator Bob Casey, a Pennsylvania Democrat. "I hope Senator Lieberman will focus on the former and say what he wants to about Senator McCain and why he's for him as opposed to attacking our nominee." Casey was one of a few Democratic Senators even willing to discuss Lieberman. Of the dozen polled one afternoon last week after the caucus met with top Obama strategist David Axelrod — a meeting Lieberman discreetly skipped — many simply declined comment. California's Diane Feinstein bit out, "It obviously hurts, there's no question about that and that's all I have to say."

It's a fine line Lieberman's walking, and one that could have serious consequences. The Democrats are well positioned to pick up several Senate seats in November, and if he's no longer the 51st vote, Lieberman may find himself facing open calls to throw him out of the caucus. No one likes to play the cuckold for long; sooner or later they ask for a divorce.