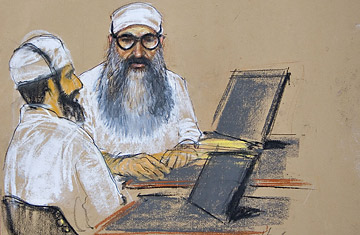

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, left, and Waleed bin Attash sit during their arraignment at Camp Justice, June 5, 2008, in Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base, Cuba.

Confessed terrorist mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed told U.S. military judge Ralph Kohlman on Thursday that he would represent himself at his tribunal, and that he welcomed the death penalty that would make him a "martyr." But Mohammed was clearly taking advantage of the opportunities offered by his arraignment in a heavily guarded, high-tech courtroom at Guantanamo on charges of helping to murder nearly 3,000 people in the 9/11 attacks. For one thing, his courtroom appearance offered him his first chance in five years of near-total isolation to communicate with his four co-accused.

Mohammed, who wore a full gray and black beard, turban, white robes and owlish horn-rimmed glasses, was clearly the leader of the five, seated at the front of the courtroom alongside his defense lawyers. Throughout the morning session, he conversed animatedly with his fellow defendants, Mohammad bin Attash, Ramzi Binalshibh, Ali Abdul Aziz and Mustafa al-Hawsawi, seated in a row behind him with their own lawyers. (Only Binalshibh was shackled.) The men spoke in Arabic among themselves, at times joking and appearing to coordinate strategy. Mohammed frequently conversed with bin Attash, seated directly behind him, who then appeared to relay messages to the other defendants.

Near the end of the day-long arraignment, Army Major Jon Jackson, the lawyer for Mustafa al-Hawsawi, charged that his client had been "intimidated" by Mohammed and other defendants into rejecting legal counsel and electing to represent himself. Lawyers for all the defendants confirmed to TIME that their clients had been brought to court about 15 minutes before the arraignment began, and had held an extended conversation in Arabic. At first, Mohammed and Hawsawi were the only two defendants present and, according to Maj. Jackson, it was then that Mohammed confronted his client. "Do you think you're in the American army now?" Jackson quoted Mohammed as demanding of his client in a loud voice. Hawsawi began "shaking" and appeared "disturbed" during the exchange, which occurred as the two prisoners were seated four rows apart.

After that, Mohammed allegedly told Hawsawi, "Don't talk to your lawyer, talk to me," Jackson recalled. The incident could prove important, because Hawsawi appeared to have changed his decision to be represented by a lawyer as a result of the exchange. "When I met with my client in the holding cell before the arraignment he was very clear that he intended to have a lawyer," Jackson said. "As soon as he got in that courtroom, everything changed." Trial observers said it was very unusual, if not unknown, to permit co-defendants to have such prolonged contact during the sensitive arraignment process in a conspiracy trial, in which decisions can be made that shape the proceedings. It remained unclear whether the opportunity for an extended conversation between the prisoners had arisen inadvertently, or had been planned by the court for prisoners who have been isolated for years and held under the strictest control and security. Whatever the reason, the result was clear: All five chose to represent themselves in court, with lawyers on hand to provide advise as needed, a move that forshadows further coordination of strategy between the defendants.

Another lawyer for Binalshibh told the court that her client is taking "psychotropic" medication that may be impairing his judgement and selection of counsel. Binalshibh countered that he was being forced to take the medication, but remains perfectly capable of representing himself. But several other lawyers also objected to what they described as Judge Kohlman's rush toward selection of defense counsel. Kohlman repeatedly cut them off, warning one to "never interrupt me" and ordering others to "please sit down." Kohlman then rejected defense motions for any delay.

Kohlman also provisionally rejected a request from Mohammed that the defendants be allowed to discuss their defense among themselves outside the formal court proceeding. He also tried to cut off talking between the defendants, admonishing them at one point, "Will the accused please pay attention to what I'm saying and stop having side conversation."

Polite, and addressing the judge with confidence in clear, slightly broken English, Mohammed persisted in speaking to fellow prisoners and made clear he plans to follow "God's law." At the close of the morning session, he was asked to approve a drawing of him rendered by a sketch artist. "Look at my FBI photo. Fix the nose. Then bring it back to me," he reportedly answered. Mohammed said he rejected legal representation from U.S. military lawyers under the command of President Bush, who he charged "is waging a crusade in Afghanistan and Iraq and our holy lands." Chanting verses from the Koran in a singsong voice, he repeatedly referred to his interrogation and five years in U.S. custody, telling the judge, "All of this has been taken under torture ... and you, Mr. Kohlman, know that very well."

The arraignment marked Mohammed's first public appearance since being captured in Pakistan in 2003. During a March 10, 2007, Guantanamo hearing that designated him an enemy combatant, he boasted he was "responsible for the 9/11 operation from A to Z," according to a Defense Department transcript, and has also claimed that in 2002 he personally beheaded Daniel Pearl, the Wall Street Journal correspondent kidnapped in Pakistan.

The five defendants will be asked to enter pleas as part of the arraignment, which is showcasing the Bush Administration's plan to try some 70 of the 270 detainees at Guantanamo by military commission. Sixty print and television reporters were flown to Cuba on a military plane to cover Thursday's arraignment. Strict rules are in effect to protect classified information divulged in the new, $12 million courtroom equipped with multiple television cameras, some of which feed video to outside observers, while others monitor the defendants for security reasons. No one in the court is armed, but burly uniformed guards sit close to each prisoner poised to stop any disturbance.

The soundtrack of the courtroom video feed is broadcast on a 20-second delay to allow a security officer to block transmission of statements that might contain classified material. Every statement from any of the defendants is presumptively considered classified, and each has been warned not to discuss secret material — presumably involving details of where they were secretly interrogated abroad and other sensitive matters.