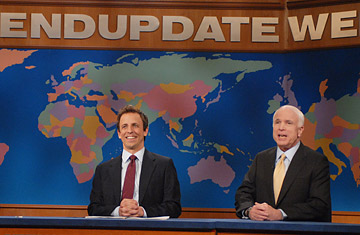

Senator John McCain on Saturday Night Live, May 2008.

Even in a campaign season where presidential candidates are turning up on late-night talk shows more often than stars of Judd Apatow comedies, The Colbert Report of April 17 was a perverse milestone.

Just a few days before the Pennsylvania primary, Colbert scored a hat trick: three Democratic candidates in one night. First came a "surprise" walk-on by Hillary Clinton, who showed up to help fix a technical snafu with the show's video feed. "I just love solving problems," she quipped. "Call me anytime. Call me at 3 a.m." Clinton's former rival John Edwards came next, joking about what he wanted from the two remaining Democratic candidates in return for his endorsement. (Help for the poor, and a pair of jet skis.) Finally, Barack Obama chimed in via satellite, doing a riff on the tough debate questions that had irked him two nights before. "I think the American people are tired of these games of petty distractions," he said, before adding "Distractions" to the list of pet peeves on Colbert's "On Notice" board, alongside Grizzly Bears and Jane Fonda.

Good sports all — unless, that is, you're one of those old-fashioned voters who still think what a candidate says on the campaign trail actually matters. Those ominous TV ads touting Hillary's readiness to handle any world crisis at 3 in the morning? Even the candidate herself began treating them as a joke. Edwards' insistence that the eventual nominee must promise to carry on his fight for the underprivileged? Worthy of a snicker. Obama's gripe that presidential debates ought to focus on serious issues like Iraq and the economy, not trivia like flag lapels? Oh, lighten up.

It's hardly news that late-night comedy shows provide the ironic lens through which we view everything that happens in the public arena. And that no candidate for high office can hope to be taken seriously unless they're willing to stop being serious and take part in the japery. But now that the most gag-filled primary season in history is lumbering to an end, I have a modest proposal: Cut it out! The comedy campaign has gone from novelty to inanity, damaging not just the great tradition of renegade political satire, but whatever shaky credibility is left in our political process.

This is a relatively new phenomenon. The best political satirists of the 1950s and '60s were prickly outsiders, scornful of the high and mighty. When Mort Sahl sat on a nightclub stool and took out his newspaper to deconstruct the day's headlines, or Lenny Bruce lashed out, in X-rated language, at the political and moral hypocrisy he saw around him, they hardly expected, or wanted, the targets of their satire to show up onstage at the hungry i and join in the laughs.

Things began to change when political satirists took on a dual role as talk-show hosts. Johnny Carson, whose topical wisecracks helped define the national mood in the 1970s and '80s, played it strictly down the middle and made sure nothing cut too deep; after all, you never know which butt of your jokes might show up one night on the guest couch. In truth, relatively few of the era's political leaders appeared on Carson's show: not Jimmy Carter, or Gerald Ford, or even Ronald Reagan after he became a presidential candidate. One exception was a young Arkansas governor named Bill Clinton, who came on a few days after his windy speech at the 1988 Democratic convention nearly bored everyone to death. Bill joked about it and did some timely damage control. The rest is history.

The current late-night satirists, however, owe less to Carson than to other groundbreaking stand-ups of the '70s, like Robert Klein. In his sharp routines on Watergate and other Nixon-era outrages, Klein didn't depend on cool, Carson-style one-liners. He re-created the offending scenes and characters and skewered them with parody, sarcasm and ironic hyperbole. It was a more subversive and conspiratorial form of satire, luring the audience into the comedian's world view, carried along by attitude, not jokes.

Similarly, Jon Stewart rolls out a daily parade of video clips and responds to them, not with gag lines, but with an arched eyebrow, an expression of mock befuddlement, or mock-angry outburst dripping with sarcasm. Colbert's nightly impersonation of a pompous rightwing pundit, too, is one long wink to the audience — we're all hip to the put-on. David Letterman's Great Moments in Presidential Speeches — maybe the quintessential political satire of the Bush era — don't even need any reaction from the host; the absurdity is there for all to see.

For politicians who spend most of their time trying to convince us of their earnestness, navigating this ironic comedy landscape can be tricky, sometimes excruciating. Last weekend on Saturday Night Live, John McCain tried to defuse the age issue by making his own old jokes, cracking about his "children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, great-great grandchildren..." Yet it was McCain's former rival Mike Huckabee who provided the campaign's most squirm-inducing moment, in his own SNL appearance a couple of months earlier. After a tongue-in-cheek Weekend Update commentary, the punch line was that the candidate wouldn't leave the stage after the bit was over. This while Huckabee was still insisting, out in the real world, that he wouldn't leave the race because his candidacy wasn't over. So who are we to believe — the comedian or the candidate?

Both of them, comedians and candidates, are thrown off their game in these encounters. Ironists like Stewart and Colbert have to do an awkward dance between sobriety and sarcasm when the real goods walk into the studio. Interviewing Obama just before the Pennsylvania primary, Stewart played it straight, before a closing zinger — demanding to know, on behalf of the American people, "Will you pull a bait and switch, sir, and enslave the white race?" Obama's ear-to-ear grin was maybe his least sincere moment of the campaign.

Yes, it's nice to have candidates with a sense of humor. But would it be too grumpy to suggest that a little respect for the old fault lines —satirists dish it out, public figures take it — might be a boon to both sides? Or that this confusion of realms could be one reason for the growing cynicism and dwindling trust in our political leaders? It's hard to take anything a candidate says seriously when it can be rendered inoperative two nights later with a Letterman Top 10 list. When she was caught making up a story about sniper fire in Bosnia, Clinton's apology was so casually dismissive you might have thought it was just another Jon Stewart bit. And it's probably just a matter of time, once the Rev. Wright resurfaces as an issue in the general election, before Barack Obama really is asked (Stephanopoulos, want to take this one?) whether he intends to enslave the white race.

At least you can at least be sure of one thing. If he does, it will get a laugh.

Richard Zoglin's book Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-up in the 1970s Changed America was published in February by Bloomsbury.