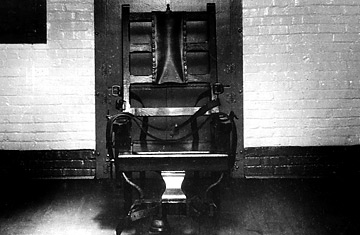

An electric chair in Trenton, New Jersey.

No criminal has been executed in New Jersey since 1963, so the fact that Gov. Jon Corzine has just signed a bill abolishing the state's death penalty might seem symbolic. But in a country where capital punishment exists mainly as a symbol, that's precisely the point.

Critics of capital punishment hope that New Jersey's step — becoming the first state in modern times to repeal its death penalty — is a sign of things to come. Until Monday's signing, the Garden State was one of five states where capital punishment remained on the books but has been unused for decades. Another five states have each executed only one prisoner during the past 40 years.

Early this year, a commission appointed by the New Jersey legislature concluded that capital punishment — which requires a more elaborate process at trial and in appeals — costs too much, financially and emotionally, to maintain it as an empty gesture. One study considered by the commission estimated that New Jersey communities and courts had spent a quarter of a billion dollars above and beyond the cost of non-capital murder trials to try to satisfy the exacting standards for death penalty cases established by U.S. Supreme Court and interpreted by skeptical lower courts. A more conservative estimate put the excess cost at $1 million per inmate. A life sentence without possibility of parole can accomplish as much, the commission decided, but without the added burdens.

One member of the panel, James Abbott, chief of police in West Orange, N.J., said the emptiness of a penalty that is so rarely imposed persuaded him to go along with the group's finding that New Jersey's death penalty served no purpose. Of the 60 death sentences recommended by New Jersey juries under the current law, 57 have been reversed on appeal. "If I were ever to be killed in the line of duty, I would never, ever want my wife and three daughters to suffer the way these families suffer with this arduous and never-ending court process," Abbott told the Associated Press.

New Jersey is not the only state asking these questions about costs and benefits. In states like Maryland, New Mexico and South Dakota, legislative efforts to repeal the death penalty — once considered hopeless — now appear to be within a few votes of success. Blue-ribbon committees similar to the one in New Jersey have been appointed in places like Illinois, Tennessee, Maryland and Florida.

All this comes against a backdrop of declining use of the death penalty nationwide. The number of death sentences and the number of executions have both fallen dramatically since the turn of the century — though America's courts continue to pronounce doom in far more cases than doom is delivered. Fewer than 3% of death row prisoners are executed in any given year.

The long-range hope of death penalty opponents — and the reason why death penalty supporters were lobbying to save New Jersey's unused death penalty right up to the final vote — is that a trend toward abolition in the states might build into a Supreme Court ban on all capital punishment. No one believes such a step is imminent, but in recent years the high court has cited changes in state laws to justify bans on capital punishment for juveniles and mentally retarded prisoners. In those cases, the justices looked to state legislatures as harbingers of society's "evolving standards of decency," and leveraged the actions of a relatively small number of states into rulings that bind the entire country.

Richard Dieter, director of the anti-capital punishment Death Penalty Information Center, is wary of talk about how symbolic victories might build into a real change in national policy. But he suggests that for the first time in decades, momentum may be running against capital punishment. "I don't think we're there yet," he says. "But we're farther along than I expected us to be."