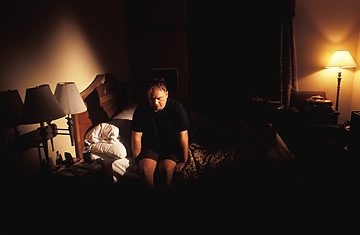

A soldier suffering from PTSD in his room at Walter Reed hospital.

Is the toll of fighting an urban guerrilla war harder on reservists than on active duty soldiers? An authoritative new study thinks so, saying army reservists — who constitute nearly a third of the 1.5 million Americans who have served in Iraq — require psychological treatment at twice the rate of active duty soldiers. The study, released on Veterans' Day week, was issued just as Congress looks for ways to lighten the mental health burden on the country's uniformed ranks.

The study by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) focused on 88,235 soldiers who were screened twice: first when they returned from Iraq; and second, after three to six months at home. Although reservists had similar battlefield experiences as active-duty troops, they suffered substantially higher rates of depression, interpersonal conflict, suicidal thoughts and post-traumatic stress disorder — a disparity that grew dramatically over time.

Both groups reported higher rates of psychological problems in the follow-up screening, leading authors from Walter Reed Army Medical Center to conclude that assessing soldiers right after they had come home significantly underestimated the mental health toll of the war. For example, only 3.5% of active-duty soldiers and 4.2% of reservists were initially worried about fighting with spouses, family members and close friends. Asked several months later about actual conflicts, rates rose to 14% and 21.1%, respectively. Depression rates doubled for active duty and tripled for reserve soldiers over time.

A combination of things — the thrill of coming home, leave or the natural act of repressing trauma — may delay the onset of problems, said Colonel Charles Milligan, the lead author. "Some problems, like depression, may take some time to develop," he told TIME. "Someone may have lost a buddy but didn't have a lot of time to dwell on it in the combat theater," said Milligan, a psychologist at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. "Once they're back home, they have a little more down time and it may be weighing on them."

The psychological baggage of Iraq war veterans is well known — other reports say a third of returning soldiers have mental health issues. But the latest JAMA effort is striking for its findings on reservists. The study found 42.4% of reservists had a mental health problem identified by a clinician, a high rate that the authors attribute to the fear of losing military health benefits, separation from a supportive military community and the stresses of civilian work.

The study is already being cited by those advocating systemic change in Veterans Administration programs. "Every one of these studies is another canary in the coal mine," said Paul Rieckhoff, of Iraq & Afghanistan Veterans of America. He predicted dire results — increased homelessness, suicide and marital and employment problems — unless something is done by Congress to improve mental health services for vets.

The $87.7 billion VA appropriations bill for this year, including a $2.9 billion increase in specialty mental health programs, was originally packaged together with other legislation vetoed by the President. It was sent back to a House-Senate conference committee for re-passage. An ambitious VA authorization bill passed a Senate committee in August, but has shown no signs of moving on the floor. It would require the VA to provide mental health evaluations for veterans within 30 days of a request and expand counseling services for veterans at risk of homelessness from six to 12 locations nationwide.