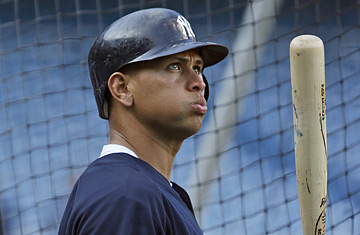

New York Yankees Alex Rodriguez gets ready to take batting practice.

It's a word that harks back to baseball's uglier days, one that at the time made even millionaire players almost sympathetic figures. A word that, in the sport's current booming business climate, is somewhat shocking to hear being tossed around.

But there it was, thrown out by the players' union in the owners' direction late last week like a wicked split-fingered fastball: Collusion.

Ever since owners had to cough up nearly $300 million for conspiring to keep free agent salaries in check in the 1980s, collusion hasn't been a serious issue of concern. And how could it be, given the soaring contracts of the past decade that culminated in the 10-year, $250 million deal the Texas Rangers gave to Alex Rodriguez in 2000? But it's those very same stratospheric salaries — and in particular the new deal that A-Rod and his agent-provocateur Scott Boras are reportedly seeking (how about $350 million over 10 years?) — that has much of baseball suddenly speculating about a return of the illegal practice.

As the free agent signing period gets going this week, the union is sufficiently frightened that the fix could be in again that it is gearing up an investigation. "Any such activity with respect to free agents is clearly improper," says Donald Fehr, the executive director of the Major League Baseball Player's Association. "We expect to look into the situation, and are prepared to take appropriate action to respond to any collusive behavior, and to make sure the rights of free agent players under the Basic [collective bargaining] Agreement are fully protected."

What's fueling Fehr's concerns? For one, during baseball's general managers' meetings in Orlando last week, Theo Epstein of the Boston Red Sox and Larry Beinfast of Florida Marlins introduced a new element to the gathering. The GMs assembled in one room and each stated what their off-season priorities were, and who might be available in trades. To the execs, it was an efficient way to horse-trade information that they typically would share in various time-consuming, one-on-one conversations. Some teams spoke in general terms, others got a little more specific, Major League Baseball insists it was not a conspiracy meeting.

"Any suggestion that such a discussion violates the Basic Agreement is absurd," says Rob Manfred, baseball's lead labor lawyer. Still, the union thinks the meeting was suspect. Several press reports have also suggested that Commissioner Bud Selig — angry about both the scope of A-Rod's free agent demands and the timing of the opt-out from his New York Yankee contract (during the waning moments of this year's World Series, thus overshadowing the sport's signature event) — could be working the back rooms to keep A-Rod from scoring another pay raise. Manfred calls such allegations of tampering "totally unfounded."

Given baseball's history of collusion, and some recent comments by pundits as well as executives in the press, you can't blame the union for its aggressive stance. ESPN contributor Stephen A. Smith only half-jokingly suggested a little collusion might be in order considering how much A-Rod was seeking. And when talking about A-Rod's hefty demands, outgoing Atlanta Braves general manager John Schuerholz told a radio interviewer: "I think it's obnoxious. I admire and respect Alex Rodriguez as much as any ballplayer that has played the game. But for someone to suggest that this is a valid salary level for a professional athlete, no matter what kind of voodoo economics they can do in analyzing the books of MLB, it's absolutely asinine. It only takes one team to have the wherewithal with that player, and then that player and his representatives think 'Well, this is what the market value is.' It's crazy, and so is that level of compensation." Was Schuerholz, who will relinquish his GM duties but stay on as Atlanta's team president, just taking a parting shot at Rodriguez? Or was he sending his colleagues a not-so-subtle signal to stick it to A-Rod? At least one National League GM, who did not want to be identified, expressed support for Schuerholz's sentiments. "We're about team building, not individual players," he says. "The Texas Rangers could talk volumes about how that [deal] worked out."

Still, the union may be going a little overboard. It recently accused New York Times columnist Murray Chass of being an "enabler of collusion" by writing a piece in which he surveyed about a dozen GMs of their possible interest in A-Rod and found very few, if any, takers.

On the issue of collusion, moreover, the players may be victims of their own success. Thanks to the absurd deal the Rangers gave to Rodriguez, collusion against the superstar will be difficult to prove. Baseball may be flush with $6 billion in revenues, and Rodriguez is coming off another monster season, but every GM can legitimately make the same case: the Rangers wildly overpaid for him back then. How many division titles did the Rangers win with Rodriguez on the team? Zero. The Yankees traded for that contract after the '03 season (he was set to make about $27 million per year on the last three years of that deal before he opted out), and how many World Series titles did they win with A-Rod? Zero. Meanwhile, the Colorado Rockies and Cleveland Indians — one team the National League champ, the other one game from a pennant — invested in young, relatively cheap talent and succeeded.

It's called common sense, not collusion. "The fact that one player doesn't get what he wants — that's not even close [to collusion]," says Rick Karcher, a sports law professor at Florida Coastal School of Law.

Minus a smoking gun, A-Rod shouldn't expect much help from the arbitrators. Back in the 1980s, the evidence was stark. The arbitrator found, for example, that the American League president and two owners — Jerry Reinsdorf, who still controls the Chicago White Sox, and one Bud Selig, then owner of the Milwaukee Brewers — called the president of the Philadelphia Phillies to dissuade him from signing Lance Parrish, a free agent catcher from the Detroit Tigers.

Moreover, such collusion in the '80s was apparently widespread. Stars like Morris, Tim Raines, Andre Dawson, Kirk Gibson and Carlton Fisk were all mysteriously offered bad deals, if any deals at all. Collusion is easier to prove if a group of players are being shortchanged. Aside from Rodriguez, this year's free agency class is a notably weak. It most likely won't take a conspiracy to hold salaries in check. There's no need to collude against first baseman Doug Mientkiewicz.

What's more, with George Mitchell's report on baseball's sordid steroid history due out by the end of the year, the owners wouldn't be dumb enough to toss another scandal into the off-season mix, right? "Hopefully, baseball has learned its lesson from the past," says Karcher. "From a business perspective, they're doing so well from so many different standpoints, I'd just be surprised if collusion would take place." But remember, we're talking about baseball here, where there's always room for another botched play.