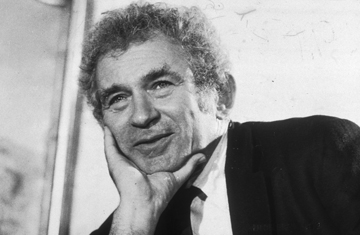

American author Norman Mailer during a 1980 press conference to discuss his book on Marilyn Monroe in New York City

(2 of 2)

His other great topic was manhood, and the problem of how to achieve it in a culture subsiding into room temperature. Like Papa Hemingway, Mailer was fascinated by boxers and liked their company. He was also prone to drunken fistfights. As for women, he had something close to a mystical view of sex, of the female body as a mystery that a man must enter and possess. And his hatred of the emerging order of techno-rationalism extended to a distaste even for birth control. All that, plus the fact that in 1960 he had stabbed his second wife Adele — though badly injured, afterwards she refused to sign a complaint against him — made it inevitable that he would become one of the main targets of feminist writers in the late '60s and early '70s. His reply was The Prisoner of Sex, a defense of some of his favorite writers — D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller — and of his own embattled notion of relations between the sexes as a perennial test of strength.

For a long time another of Mailer's fixed ideas was borrowed from Wilhelm Reich, the apostate Freudian who was prosecuted in the '50s in connection with his claim that he could treat cancer with his magical "orgone" box, which he believed collected life energies. (Mailer actually built one for himself.) Reich believed that cancer was an outgrowth of sexual repression, the body's lethal reply to the denial of primal needs. Mailer could see that America was a repressed society, and couldn't resist joining in the conclusion that self-denial was literally malignant. It was an idea that effectively blamed the patient for the illness. In 1978, Susan Sontag would strike back with Illness as Metaphor, a book that demolished the habit of discussing cancer or tuberculosis in any such terms. Sontag had none of Mailer's percussive lyricism, but on cancer she was right, he was wrong.

But by that time Mailer was on to much bigger things. Gary Gilmore was a convicted killer who insisted that the state of Utah carry out its intention to execute him. The magnificent, haunting (and Pulitzer Prize-winning) book that came out of the Gilmore execution and the attendant media circus, The Executioner's Song, turned out to be the high-water mark of Mailer's career. There were many titles after that, but none with anything like the same power. The spare immensities of The Executioner's Song turned into the sheer endlessness of Ancient Evenings, his grand blunder into the Egypt of the pharaohs. (That book is also as a close as he got to producing the long promised but never delivered cycle of novels tracing the story of one Jewish family from ancient times to the present, which may be just as well.) There was Tough Guys Don't Dance, a detective novel that also became a movie, with Ryan O'Neal, one of four films that Mailer directed. There was Harlot's Ghost, a long novel about the CIA.

With all those ex-wives and children to feed, there was also no end of non-fiction literary shopwork — a dozen or more books on grafitti, Picasso, Lee Harvey Oswald, and a long one on Marilyn Monroe that borrowed heavily from other bios, at least for the bare bones of her story. The strenuous speculations on the meaning of Marilyn were entirely his.

There was worse. Mailer had always had the hipster's fascination with outlaws, including himself. What was The American Dream after all but an extrapolation from the interior life of Mailer after he had stabbed Adele in 1960? But after the great success of the Executioner's Song, it was Mailer's bad luck to run across another charismatic hoodlum. Jack Henry Abbott had spent most of his adult life in prison. In the '70s he started writing to Mailer, who was impressed enough by his furious and defiant letters about prison life to help him turn them into a book, In the Belly of the Beast. In 1981, with Mailer's help, Abbott was released on parole. Six weeks later he got into an argument with a young waiter at a restaurant in lower Manhattan, pulled out a knife and stabbed him to death.

The Mailer who romanticized violence — he hated that description, but it's the unavoidable one — was now the man who had aided and abetted it, however unintentionally. It had been one thing to take risks with his own dignity. This time someone else had paid with his life.

But make no mistake, when he died on Saturday, something important was lost. Even at his most exasperating and contrarian — especially at his most contradictory and contrarian — he was an indispensable cultural voice. And there is no one now even bidding to take his place with anything like the same force and originality of mind. My favorite Mailer quote will always be this one: "How dare you scorn the explosive I employ?"

Norman come back. Nothing is forgiven.