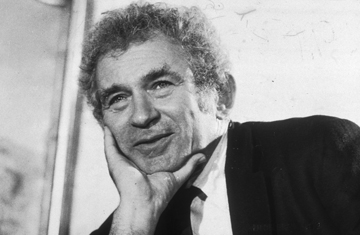

American author Norman Mailer during a 1980 press conference to discuss his book on Marilyn Monroe in New York City

"His consolation in those hours when he was most uncharitable to himself is that taken at his very worst he was at least still worthy of being a character in a novel by Balzac, win one day, lose the next, and do it with boom! and baroque in the style."

— Armies of the Night

You can't say he didn't live up to his own expectations. In ten novels and almost two dozen other books, Norman Mailer not only did it with boom. He did it with brains and wit and nerve. He became what you might call the foremost pronouncer of his time.

He was, of course, a great conundrum. There was paradox even in his voice, which hovered in some undisclosed location between the Brooklyn of his youth and the Harvard of his student years. He saw himself, in all his complexities, as some essential figure of his epoch, so that the arc of his own career was one of his perennial subjects. This was not just a measure of his egotism — which was boundless — but also of his certainty that the judgment upon him of public opinion was, itself, an important sign of the times. He could never stop measuring his reputation against every other writer's; he spent years waving his Brooklyn matador's cape at Hemingway, boxing with Tolstoy (and anybody else who got in his way) and always licking his own wounds. Mailer's forte was intricate readings of his own inner conditions. His mistake, sometimes, was to believe in them too much as a guide to the wider world. But as Mailer would have asked: What else do we have to go on?

He was just 25 when he became abruptly and unmanageably famous for his first novel, The Naked and the Dead. It was 1948, America was looking for its Great War Novel and there was Mailer with his jug handle ears and his curly hair and a teeming book based on his experiences as an infantryman in the South Pacific.

It became a huge bestseller. But fame turned fickle on him, or maybe vice versa. He turned out to be too flighty, too impious and vainglorious to fill the role of anointed American writer, the thinking man's thinking man. Various literary and media establishments turned against him. As the '50s wore on, Mailer published Barbary Shore, a middling novel about an amnesiac writer and some despairing Trotskyists in Brooklyn, and a better but still underrated Hollywood novel, The Deer Park. He helped found the Village Voice, the model for all subsequent alternative weeklies, or at least the good ones. But his standing kept falling.

When it appeared that his comet had stalled badly, Mailer took decisive action. He fashioned a collection of short pieces into Advertisements for Myself, a triumph of swaggering literary sales talk. It contained a couple of his best short stories, including "The Man Who Studied Yoga," and a choice selection of essays, including "The White Negro," which epitomized the headlong intellectual bravado, even to the point of absurdity, that we would eventually think of as Maileresque. (It was "The White Negro" that included the notorious proposal that a hoodlum who mugged a candy store owner might be thought of as "daring the unknown.") Advertisements for Myself wasn't a bestseller of the magnitude of The Naked and the Dead. But it got talked about in all the right places, and remains a treasure house of contrarian thinking. Mailer had now re-established himself.

And wouldn't you know it, the rich kingdom of 1960s was about to open before him. Its new standards of misbehavior, its ferocities, its treacheries, its Kennedys — all of it answered to Mailer's disposition. For Esquire and other publications he began producing peerless meditations on the sensibilities (and the treacheries and the Kennedys) of his time. In 1968, he found his stride with Armies of the Night, his brilliant "non-fiction novel" about the October 1967 anti-war March on the Pentagon. The first of two Pulitzers came his way. These were the years of Mailer at his most visible, when he took up every kind of public intellectual battle, and even ran a boisterous, quixotic and very entertaining campaign for mayor of New York.

All through his career Mailer would carry with him a few persistent preoccupations. One was that technology was the devil's instrument, the means by which everything that made us human would be gradually leached away. It wasn't just the atomic bomb that Mailer detested. He could write about "the scent of the void that comes off the pages of a Xerox copy." (You felt sometimes that there was no prose too purple for him not to attempt it.) He hated the telephone so much he wouldn't give phone interviews.