Alabama has became the first state in the Union to approve a textbook for a course about the Bible in its public schools, and its surprisingly uncontroversial decision may prove to be a model for others.

According to Dr. Anita Buckley Commander, the Alabama Director of Classroom Improvement, there was no opposition to the October 11 vote by the state Board of Education to include The Bible and Its Influence on the state's list of accepted textbooks. The Board held a hearing on the issue and no one showed up; the book was approved by a vote of 8-0.

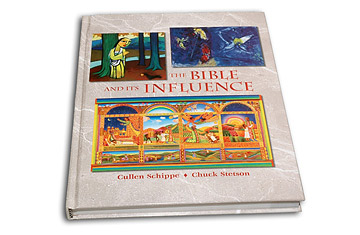

The textbook is a product of the Bible Literacy Project, founded and run by Chuck Stetson, a conservative Christian New York-based equity fund executive. Assessing scripture and its subsequent influence on literature, art, philosophy and political culture, it was specifically designed to avoid the Constitution's church-state barriers. Although the text, which has been on the market for two years, is now taught in 163 schools in 35 states, no state had previously endorsed it.

The Bible and Its Influence has a fascinating constellation of supporters and critics. Some of its more liberal champions, such as the American Jewish Congress's counsel Marc Stern, feel that the republic can not only survive but will actually benefit from public school courses on a document as culturally central as the Bible — as long as the classes avoid being devotional. Evangelical heavyweight Chuck Colson hopes that God will speak to students even through a class that is secular in intent. Those opposed to the book include secularists who argue that it already violates the First Amendment and fundamentalists who see its approach as secular and therefore diluting the value of what they see as God's inspired word.

Despite the book's smooth passage through the Alabama school board, it had caused a firestorm in the state's House of Representatives only a year ago. Democrats who liked the book — and may also have been interested in burnishing their religious credentials — had submitted a bill making it the mandatory text for any public school Bible-study classes. State Republicans who didn't like the book, and may also have wanted to deny the Democrats the political God Card in an election year, ensured by their vociferous opposition that the Democratic bill was eventually voted down in committee. Something similar happened in neighboring Georgia, where Democrats submitted a bill prescribing The Bible and its Influence, but Republicans turned it into a much less specific endorsement of Bible classes.

Precisely why the Alabama Board of Education succeeded where the legislature failed (with one distinction: the school board didn't rule out the use of other texts) remains something of a mystery. Presumably most Alabamans would welcome a public school course on the Bible, even if it were from a secular standpoint; "I don't see how [the book] would scare anyone" who has read it, comments Commander. It may be that the Board of Education, which she describes as politically "balanced," is not as caught up in partisanship as is the Alabama House. Moreover, the book was not the Board's sole focus: in fact, its attention was monopolized by a discussion about school reading texts.

Although the Bible Literacy Project officers are thrilled with its success in Alabama, they are not necessarily counting on replicating it elsewhere fast. There are 22 states with similar low-key selection methods, but they tend to consider different curriculum categories year by year, and in some states the category including a Bible course textbook will not roll around for another eight. So, says a spokesperson for the Project, "we have to sit around and wait." In other states, the book doesn't appear to fit into any of the established categories of study. And then there are the 28 states where such decisions are made by local rather than statewide school boards.

The Bible Literacy Project is philosophical about the delays created by the different legislative processes in different states. Although a more centralized legislative initiative would result in faster adoption of the text, that process can fall victim to politics, as Alabama's experience shows. And, for advocates of studying (as opposed to preaching) religion in the public school curriculum, the low-key introduction of the text, whether locale by locale or through the workings of state boards like Commander's, offers an opportunity to assess its fairness and effectiveness before it becomes a nationwide fact.