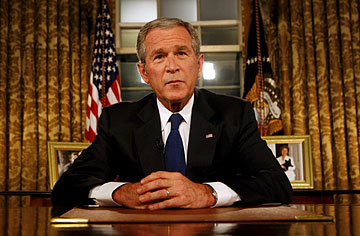

U.S. President George W. Bush in the Oval Office following his television address to the nation, Sept. 13, 2007

President George W. Bush's decision to give a major speech on Iraq in prime time Thursday night made sense on one level. The news has been relatively positive for a change, what with the stabilization in Anbar province and parts of Baghdad. Earlier in the week, Bush and the Congress got a cautiously upbeat report from Gen. David Petraeus and Ambassador Ryan Crocker that recommended a drawdown of some troops over the next nine months. So after months of asking Americans for patience, the President could finally tell them "that conditions in Iraq are improving, that we are seizing the initiative from the enemy," and that, in turn, he can "begin bringing some of our troops home."

But Bush's trumpeting of what he called a "return on success" could end up backfiring. Bringing the war into America's living rooms is never a safe political bet. And if news of a slow drawdown may be popular, Bush himself still is not. Some key Hill Republicans, in fact, were upset that he returned front and center on the issue at a time when the White House had so carefully ceded the selling of the surge to Petraeus and Crocker. "Why would he threaten the momentum we have?" says one frustrated Capitol Hill Republican strategist with ties to the G.O.P. leadership. "You have an unpopular President going onto prime time television, interrupting Americans' TV programs, to remind them of why they don't like him."

Republicans in Congress who were finally breathing a sigh of relief after months of bludgeoning on Iraq felt Bush was risking the progress he had made with those closely following the war by thrusting it in the faces of those who may not be paying attention. It didn't help that Bush said American forces would be on the ground in Iraq, as part of an "enduring relationship," well past the end of his term in office. Even conservative stalwarts like Newt Gingrich felt Bush was the wrong man for the job. "The right two people to talk about Iraq were Ambassador Crocker and General Petraeus," Gingrich said on Friday. Asked why Bush took the risk, he responded, "Call and ask [White House political honcho Ed] Gillespie."

It's not that Bush doesn't recognize that he's got problems as a messenger on the war. He reportedly told Robert Draper, author of the new White House chronicle Dead Certain, that he knows his own credibility isn't what Petraeus' is. But his aides say this is a crucial moment for the country, that public support is critical for the prosecution of the war and that the President felt it was his duty to inform Americans of the latest developments. "This is an important moment for the nation," says incoming White House press secretary Dana Perino. "The President thinks it's the right thing to do, he thinks there's a responsibility to talk to the American people... We have 160,000 troops who are on the ground in Iraq, and I think asking for 18 minutes of people's time is worth it."

One thing keeping the spirits of Hill Republicans up is the fact that their Democratic counterparts are in retreat over the war. Centrists are running for cover, adjusting to the relative progress on the ground by trying to lie low. At the same time the left is putting targets on its back, particularly with ads personally attacking Petraeus in the New York Times. Rhode Island's respected senior Senator Jack Reed tried to profit from Bush's prime time foray in the Democratic response Thursday night, but had difficulty differentiating the Democrats' proposal from the President's without sounding defeatist.

But the Democrats disarray only makes Hill Republicans all the more eager to grasp the momentum while they have it. And they have another theory for why Bush is willing to risk derailing the good news in Iraq by stepping into the spotlight of prime time television, rather than giving a speech at a military base somewhere. They claim he's "hitching his wagon" to the popular and respected Petraeus because he knows his place in history is at stake. "He's more concerned about his legacy than he is about helping his Capitol Hill Republican colleagues," says the Republican strategist.

He may be right. White House aides respond to the Republican concerns by saying: "Regardless of what the news was going to be [from Petraeus and Crocker], the President was going to speak to the nation. He's the commander in chief and it's his responsibility. It's his war."