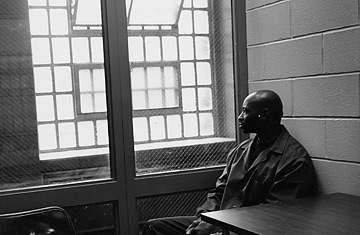

Nathan Brooks, who at the last minute accompanied a woman on her first drug deal, was sentenced to 25 years under New York State drug laws. Brooks was released in 2004.

The most painful thing to Cheri O'Donoghue about her son's incarceration on drug charges is not the imprisonment itself, but that he is serving the sentence that should go to a narcotics kingpin when all he committed, she says, was the crime of a small-time pusher. Her son Ashley was found guilty of delivering cocaine to two college students in upstate New York in 2003. He was sentenced to seven to 21 years in prison, a penalty mandated by New York's controversial Rockefeller Drug Laws. Ashley is among about 14,000 people sent to New York prisons under the Rockefeller laws, in force since 1973, which impose harsh mandatory minimum terms on even first-time offenders — meaning they could get the same sentence as a person convicted of second degree murder.

O'Donoghue once had hope for a positive change in her son's situation. That was because there was a movement to change the Rockefeller laws. The momentum behind that reform, however, has now stagnated as prosecutors and legislators fear that changes in the law are being used as loopholes to free drug lords. With no light at the end of the tunnel, she and other activists fighting for a repeal feel the laws may never change and many of the state's imprisoned — her son included — continue to languish in jail. "The movement is definitely stalled, and we're trying to gain some momentum again, but it's very hard," said O'Donoghue. "I never would have dreamed in the beginning of this that it would have taken this long to get Ashley out."

Right now, the only hope for a change is a prison sentencing reform committee set up by Gov. Eliot Spitzer that has only recently begun to hold preliminary meetings and whose final report is not expected until early 2008. The activists remain committed in their cause, but for now can only deal with the frustration of having a loved one jailed under what they feel are unfair rules. Critics say that the law ignores major drug dealers and only imprisons minor players in the drug trade. For this reason, they argue, it incarcerates a disproportionate number of minorities. Indeed, since the laws were enacted, more than 90% of those sentenced have been black or Latino, according to the group Real Reform New York.

Over the last decade, activists, ex-convicts, families, politicians and even celebrities have become increasingly vocal about the laws. Reforms to the sentencing structure were enacted with the 2004 Drug Law Reform Act, which allows for reduced retroactive sentencing, and at first seemed to bring the laws closer to repeal. But they have only applied to about 1,000 people and only 350 have been released, says Anthony Papa, an official with the Drug Policy Alliance, an advocacy group committed to changing the nation's drug laws. The reforms, he says, were not enough because the change applies to too few of the people currently serving time.

"In my view as an activist who experienced the law, this was sort of a buyoff to satisfy people who have been fighting for years," said Papa, who himself was sentenced to 15 years to life after selling cocaine to undercover cops, but granted clemency by then-Gov. George Pataki in 1997. "People saw it was watered-down reform because it really destroyed the movement, because now legislators have a tool they can use to say 'We have a law now, lets move on.'"

Instead of new legislation, Gov. Spitzer's seven-member commission will conduct reviews of the state's toughest sentencing practices, under which the Rockefeller laws fall. But it is unlikely to bring about a full repeal of the laws, leaving O'Donoghue to wonder if a change will ever come. "These things keep carrying over and you just wonder when it's all going to be done," O'Donoghue asked. "When we get the final report? After the next legislative session?"

Activists like O'Donoghue and Papa argue the stiffest penalties should be reserved for major narcotics traffickers, not small handlers. But the reason they have gained little in their fight is that some state legislators believe the changes in the law were enough and that many of those who have already been released are really major drug traffickers who should still be imprisoned, and further reform could prove dangerous.

"We did the reform and as a result, we provided for discretion and reductions in sentencing," said State Sen. George Winner, who explained that the changes have already resulted in loopholes for people who once controlled major drug operations. "I am not in favor of further weakening the drug law sentencing provisions. I agree that the drug kingpins should have the stiffest penalties, but some of them are using the reforms to their advantage and getting out. As a result of these things, I think we should go slow about it."

Bridget Brennan, a special narcotics prosecutor in New York City, has the same fear as Winner that violent offenders and drug kingpins are beginning to win reduced sentences. "There was a mythology about who is serving these sentences," said Brennan, who was a homicide prosecutor during the height of the city's crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. "It was the image of a woman forced to be a drug courier. But when we looked at those applying to change their sentences, there were only two women: one who supervised the shipment of 155 kilos of cocaine and the other had more than a pound of cocaine in her apartment."

"There is no statute to address the narcotics trafficker who we commonly see in New York City," she said. "As a homicide prosecutor, 60% of my cases came from drug sales. I don't want to see this city again the way it was."

Until they win a change in sentencing guidelines, activists hope to win support for their cause simply by spreading the word. They hope a planned wide release of a documentary entitled Lockdown USA, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2006, will help restart a push for reform. "The problem is that they are using a prison cell to address what should be public health issue," says Gabriel Sayegh, a project director at the Drug Policy Alliance. "This isn't the criminal justice system we're supposed to have in this country."