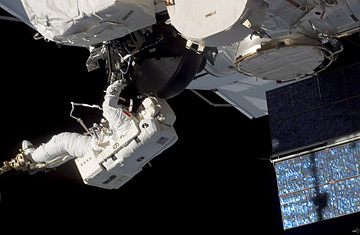

Astronaut Dave Williams performs construction and maintenance on the International Space Station.

There is no easy way to fix the gouge in the Shuttle Endeavour. In-orbit repair options are limited and, since any fix would have to be made by robotic arms and astronauts in awkward space suits, the process would be fraught with the potential to make the problem worse. Still, Mission team chairman John Shannon said that, according to his team's analysis, the damage should pose no risk to the astronaut crew on the return home. There is, however, potential for more damage to the shuttle itself on re-entry into Earth's atmosphere when temperatures in the rear of the ship could reach 2300 degrees Fahrenheit. Shannon and his team will now have to decide what to do next. And the results of that decision will reflect the success of reforms set in place after the last shuttle disaster.

The implications of losing a third shuttle either through another horrific tragedy or abandonment are severe. It would certainly end the shuttle program itself, jeopardize the International Space Station and the Hubble Telescope, which are serviced by shuttles, and potentially cost the nation thousands of space-related jobs and, less tangibly but still importantly, the loss of national pride. "The management is much different than it was four years ago," Florida Sen. Bill Nelson assured TIME. "I think they have the toughness if they have to make the tough decisions." The old NASA style, harshly critiqued by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board and summed up by Nelson as "arrogant," was susceptible to scheduling and political pressures, but easily and disastrously shrugged off safety concerns from engineers on the line, leading directly, Nelson says, to the two shuttle losses.

The new and improved NASA is restructured in an attempt to insulate technical and safety decision makers from the budget and schedule keepers. In practice, Johnson Space Center spokesman James Hartsfield says the new mission management team looks a lot like the old team, but with more people included in the inner circle, more freewheeling communication, and more hard data collected on each launch on which to base decisions. Indeed, a scenario similar to the current one with Endeavour was more or less envisioned in the "Return to Flight" (RTF) report that was issued following the 2003 loss of Columbia and her crew, whose fates were sealed by a gouge in the more critical leading edge of the shuttle wing. The RTF report anticipated more tile shedding and potentially crippling damage; and as a last resort, the shuttle crew would abandon ship and be given safe haven aboard the international space station to await a rescue vehicle.

This time, the buck stops with mission team chairman and shuttle program deputy manager Shannon, 42, a 19-year NASA veteran who served as deputy manager of NASA's Columbia task force in regular communication with the investigative board. Initial internal resistance to the new management structure noted by the RTF task force is gone, Hartsfield says. "I think it is embraced by everyone. It improves with each flight. The more you do it, the more it becomes the culture that we follow."

The RTF task force recognized that the shuttle remained physically vulnerable despite NASA's best efforts at redesign, but the decision to go on with the shuttle program hinged precisely on a new culture of management at NASA that is supposed to allow people like Shannon to make the right calls in the face of staggering consequences, and a determination to avoid backsliding into the old ways blamed equally with physical and mechanical problems for two shuttle catastrophes.

But the various reports after the Columbia disaster also pointed out another NASA proclivity: that the agency has a history of allowing improvements to atrophy with time, and that vigilance would be required to insure that NASA would "do what is right, despite easier options that may present themselves." Would we even know before it's too late if NASA had relapsed? "I'll tell you people are very cognizant and those activities are very fresh on people's minds. I think now we have really started to ingrain a new culture of looking at problems and being open and I think that's your biggest safeguard. Once you have installed that culture in place, that is your best protection," Hartsfield said.

Dr. Jonathon Clark, husband of astronaut Laurel Clark, who lost her life aboard the Columbia, says the agency can't afford to make anything less than a well-thought-out decision. "This is the kind of rock-and-a-hard-place scenario that you're in," Clark told TIME. "Realistically, I think NASA's going to do the right thing. And the right thing may not necessarily result in a good outcome, but they really are trying to do their best. The world is hanging on to what's going to happen here."