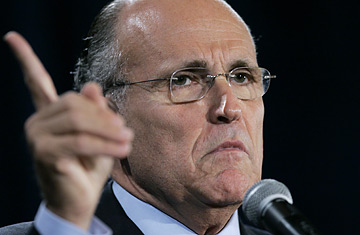

Presidential hopeful Rudy Giuliani campaigns in Iowa, June 20, 2007

How many alleged criminals can a law-and-order candidate be associated with before it starts to hurt? That's the question facing former New York City Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, following the indictment Tuesday of Thomas Ravenel, his volunteer campaign chairman in South Carolina.

Giuliani entered the Presidential campaign early this year with one tarnished pal stuffed into his baggage: his former bodyguard, police commissioner and business partner Bernard Kerik. Kerik's career began to unravel in 2004 after Giuliani urged President Bush to name him Secretary of Homeland Security — a nomination that was quickly withdrawn amid reports of Kerik's questionable business and personal dealings. Kerik eventually pleaded guilty to ethics violations while on the city payroll and remains under investigation for tax evasion and other offenses, which Kerik's attorney has said, "he didn't do."

Now Ravenel, the state treasurer of South Carolina, has been charged with cocaine possession and distribution — a felony punishable by up to 20 years in federal prison. Neither he nor his attorney has made any statement.

Giuliani's campaign lost no time in announcing Ravenel's resignation from his unpaid post, and let it be known that the indictment took them entirely by surprise. And Ravenel's offense was alleged to have occurred in late 2005, before his official association with Giuliani.

Still, for a candidate promising to track the whereabouts and lawfulness of every non-citizen living in the United States, it can't help his cause when he fails to spot possible crooks on his corporate and campaign letterhead. And Giuliani's opponents wasted no time in circulating news of Ravenel's indictment; one McCain staffer fired off a dispatch within minutes to reporters' e-mail boxes. Anti-Giuliani bloggers swiftly added the Kerik angle.

One veteran of Republican politics noted that all candidates live in fear that a prominent supporter will become an embarrassment in the middle of a campaign. A major run at the Presidency means adding hundreds of new "friends" every day – people with money or clout whose backgrounds cannot possibly all be checked.

Still, he added, the failure to look more closely at the rich, hard-partying Ravenel before appointing him to a prominent post in a key primary state could be a sign that Giuliani's operation is too casual for the long haul. "It's the kind of foul-up that suggests that his campaign team isn't functioning as well as it should," the G.O.P. source said. "Presidential campaigns are not the time for amateur hour."

Certainly not with all the trouble Giuliani has been facing in recent days. The same day he lost his South Carolina chairman, Giuliani also saw his most prominent Iowa supporter sidelined, when former Rep. Jim Nussle was summoned to Washington to serve as new head of the Office of Management and Budget. The Long Island newspaper Newsday broke the story that Giuliani was a virtual no-show as a member of the Iraq Study Group — he was too busy making million-dollar speeches and other appearances, the article claimed — and resigned from the blue-ribbon panel after being told he must either pull on an oar or get off the boat. And then there was the fact that Giuliani's own successor as New York Mayor, Michael Bloomberg, stole the campaign spotlight this week by bolting the G.O.P. and becoming an independent, stoking speculation that he might launch a self-financed third-party bid that could shake up the race.

Although he still leads the pack of official candidates in national polls, Giuliani's lofty numbers have been drifting to Earth — various national surveys showed him dropping between 2 and 6 points since early June. Meanwhile, the as-yet-unannounced candidate Fred Thompson has been rising like a hot air balloon, pulling ahead of Giuliani in a South Carolina poll and drawing even with the Mayor in one national survey.

No one survives a career in politics without crossing paths with a few rogues. But it's also true that no candidate — not even one as strongly branded in the public mind as Giuliani — entirely controls his public image. Three years ago this summer, John Kerry watched in dismay as his Vietnam record was turned against him by the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. Something similar could happen, if Giuliani isn't more careful, to Hizzoner's carefully crafted image as the scourge of wrongdoers the world over.