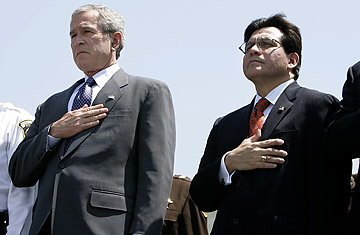

U.S. President George W. Bush, left, and U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales.

In dramatic testimony Tuesday, Comey told the Senate Judiciary Committee that he raced to the intensive care unit of George Washington University Hospital that evening to intercept Gonzales and White House chief of staff Andrew Card and prevent them from convincing Ashcroft to reauthorize the program after Justice Department lawyers had concluded that it was illegal. Comey, who during Ashcroft's stay in the hospital was acting Attorney General, has told Congressional investigators that when he arrived at the room and began explaining to Ashcroft why he was there, he was intentionally "very circumspect" so as not to disclose classified information in an unsecure setting and in front of Ashcroft's wife, Janet, who was at his bedside and was apparently not authorized to know about the program.

Comey described what happened next: "The door opened and in walked Mr. Gonzales, carrying an envelope, and Mr. Card. They came over and stood by the bed. They greeted the Attorney General very briefly. And then Mr. Gonzales began to discuss why they were there — to seek his approval for a matter, and explained what the matter was — which I will not do." Ashcroft bluntly rebuffed Gonzales, but Comey's unwillingness publicly to say what Gonzales said in the hospital room has raised questions about whether Gonzales may have violated executive branch rules regarding the handling of highly classified information, and possibly the law preventing intentional disclosure of national secrets.

"Executive branch rules require sensitive classified information to be discussed in specialized facilities that are designed to guard against the possibility that officials are being targeted for surveillance outside of the workplace," says Georgetown Law Professor Neal Katyal, who was National Security Advisor to the Deputy Attorney General under Bill Clinton. "The hospital room of a cabinet official is exactly the type of target ripe for surveillance by a foreign power," Katyal says. This particular information could have been highly sensitive. Says one government official familiar with the Terrorist Surveillance Program: "Since it's that program, it may involve cryptographic information," some of the most highly protected information in the intelligence community.

The law controlling the unwarranted disclosure of classified information that has been gained through electronic surveillance is particularly strict. In the past, everyone from low-level officers in the armed forces to sitting Senators have been investigated by the Justice Department for the intentional disclosure of such information. The penalty for "knowingly and willfully" disclosing information "concerning the communication intelligence activities of the United States" carries a penalty up to 10 years in prison under U.S. law. "It's the one you worry about," says the government official familiar with the program.

In response to questions on the legality of Gonzales' hospital room conversation, Dean Boyd, a spokesman for the National Security Division of the Justice Department, said, "I am not going to speculate on discussions that may or may not have taken place, much less attempt to render a legal judgment on any such discussions." A Senate investigator says the Judiciary Committee is weighing whether to investigate the matter formally. One consideration will be whether the Justice Department itself decides it should be investigated. Gonzales, as head of the department, would be conflicted in the matter. "The fact that you have a potential case against the Attorney General himself calls for the most scrupulous and independent of investigations," says Georgetown's Katyal.