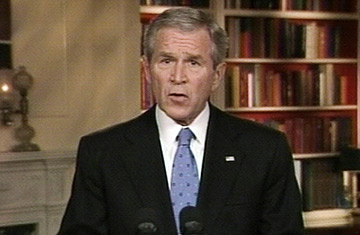

President Bush addresses the nation from the White House library in Washington.

In an nationally televised address that even some allies have said is the President's last chance to recapture the public's trust in his performance on Iraq before it flickers out completely, Bush announced the deployment of more than 20,000 additional troops to Iraq to address what he called the "urgent priority" of security in Baghdad. He told the country that the Iraqis were finally ready to take responsibility for their own security and laid out an ambitious plan to embed American forces inside Iraqi army and police units all over the capital city.

Coming after years of insisting that conditions were improving in Iraq when just about everyone could see that they were not, the speech at least paid Americans the courtesy of candor. Bush conceded that his policies were not working and, contrary to what he and other senior officials had insisted for months, that more troops were now needed. He said his new approach might not show results anytime soon and, as bad as that sounds, the alternatives were worse, he claimed. Bush did not say he had made a tragic mistake, but he came closer than he ever had before. "Where mistakes have been made," the President declared, "the responsibility rests with me."

Still, Bush faces a huge personal and political crisis over the surge. Even before the speech, moderate Republicans in his own party were busy releasing statements opposing the reinforcements and Democrats were still plotting how to bring the proposed increase to a vote in some way to allow members to express their unhappiness with the conduct of the war and the new U.S. strategy. "Escalation won't solve the problem," said Sen. Joseph Biden. "It will compound it."

The new approach emerged from more than a month of work by National Security Council aides — and after the Iraq Study Group called the situation in Iraq "grave and deteriorating" and Americans cast an unalloyed vote of no-confidence in the Iraq war at the polls in November. But rather than heed all the advice of those who proposed he engage the region diplomatically and begin a staged withdrawal from Iraq, Bush has gone his own way. And now that he has, his new approach raises at least three big questions:

1. What Will Make the Iraqis Change?

The centerpiece of Bush's new strategy is to somehow compel the Iraqis to take a variety of self-starting steps — politically, militarily, economically — that they have not to date. But there is no apparent mechanism to compel them to do so. The Study group proposed that Bush threaten to quickly reduce U.S. troop levels in Iraq as a way to compel the Iraqis to stand up; but Bush has instead decided to simply pour more troops in to help them stand up.

It is unclear if this will actually force the Iraqis to change. One reason outgoing CENTCOM boss John Abizaid had long opposed additional troops was that he believed reinforcesments would only encourage Iraqis to sit on their hands and let the Americans do the dirty work of stabilizing the nation. Bush has not explained what incentive the Iraqis have to change now — other than his suggestion last night that they would "lose the support of the American people." Asked in a briefing at the White House Wednesday what would force the Iraqis to take these steps, a senior administration official told reporters — rather astonishingly — "You'll have to ask the Iraqis."

2. How Long Will This Take?

There were no answers today to that question — and there are unlikely to be. Bush talked vaguely about benchmarks, but he did not say what would happen if the Iraqis fail to meet them. The framers of the surge — a military historian and a retired general working under the auspices of the American Enterprise Institute — envisioned it taking 18-24 months to stabilize Baghdad and did not tie it to any particular progress by the government. But whatever the levers, there is no agreement that the U.S. can sustain a surge for that long without a significant drop in readiness and a growing shortage of equipment. That was another reason the generals were so reluctant to go along with this option. Earlier this week, the new chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Ike Skelton of Missouri, a man known for being extremely careful with his words, told a gathering in Washington that fully 40% of all U.S. equipment is now in Iraq or Afghanistan — making it virtually impossible to fully train new units to get ready to go there.

3. Any Reason to Think the Iraqis Are Ready to Take Over?

This is probably the biggest piece of kabuki in the President's speech. Just a few months ago, in November, Abizaid told the Senate Armed Services committee that there were no — as in zero — Iraqi army units currently operating independent of U.S. forces. The Pentagon's inspector general has reported they lack the men, the weapons, the trucks — pretty much everything — to be ready to fight. Meanwhile, the Iraq Study Group said the police units were almost completely corrupt or infiltrated by sectarian militias. It is a little hard to square those reports with the way the President talked about the new U.S. partners in the surge last night.

The White House isn't fleshing out all of these unknowns and uncertainties, but one thing is clear; they make Bush's new Iraq policy equal parts hope and Hail Mary.