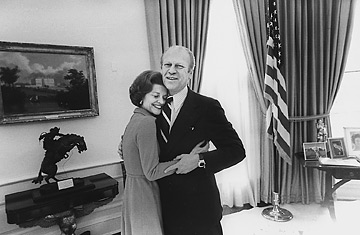

Gerald Ford, the 38th President of the United States, in the Oval Office with his wife, Betty

He was the nation's first appointed Vice President, chosen in October 1973 by President Richard Nixon under the terms of the recently ratified 25th Amendment to succeed the disgraced Spiro Agnew. Less than a year later, on Aug. 9, 1974, Nixon resigned rather than face a Senate trial on three articles of impeachment passed by the House of Representatives, and Ford took the oath to be the 38th President of the U.S.

That was a preposterous development in the career of a politician who had never run for office beyond the confines of the Fifth Congressional District of Michigan. In his first televised statement after his swearing-in, Ford acknowledged his anomalous status: "I am acutely aware that you have not elected me as your President by your ballots. So I ask you to confirm me as your President with your prayers."

His request found a receptive audience. For nearly two years, the accelerating Watergate scandals had polarized Washington, dominated news coverage and poisoned public discourse. Even to his loyal defenders, the increasingly embattled Nixon did not radiate trustworthiness and candor. On TV that August afternoon, Ford seemed the anti-Nixon: square-jawed, plainspoken, keeping steady eye contact with the camera. "My fellow Americans," he said in his reedy Midwestern tones, "our long national nightmare is over."

That verdict was premature, but people believed it because they so desperately wanted to. Besides, Ford looked like an honest, decent man, and that, as people who knew him readily attested, is exactly what he was. Frank Capra might have made a movie of Ford's wholesome life to date, although perhaps without the improbable fade-out in the Oval Office.

There were a couple of unusual details along the way. He was born Leslie Lynch King Jr. in Omaha, Neb., in 1913. Two years later his parents divorced, and his mother moved with him back to her hometown, Grand Rapids, Mich., where she met and married a businessman named Gerald R. Ford. She changed her son's name to that of his stepfather, and he did not learn his true identity until he was, as he later recalled, 12 or 13.

His stepfather's paint company weathered the Depression without serious deprivations, and Ford was a happy, popular teenager and a standout on his high school football team. In 1931 he enrolled at the University of Michigan on a full athletic scholarship. He majored in economics, played center on the Big Ten varsity squad and during his senior year was chosen to participate in the Shrine College All-Star game.

After graduation he turned down pro offers from the Green Bay Packers and the Detroit Lions and went off to Yale to coach football and boxing. After taking several courses on a trial basis, he was admitted to Yale Law School, from which he graduated in the top quarter of his class in 1941. He returned to Grand Rapids to found a law practice with his friend Philip Buchen, but shortly after Pearl Harbor he enlisted in the Navy and served for four years.

He returned to Grand Rapids to restart his law firm and pursue his interest in politics. His stepfather was active in local Republican affairs, and in 1948 Ford plunged in. He challenged the local incumbent Representative, Bertel Jonkman, in the G.O.P. primary and won, and then went on to win the general election, thanks in part to the support of Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg. Ford's experiences in the war had turned him away from Midwestern Republican isolationism, which Vandenberg opposed as well. Three weeks before after the election, Ford, in a quiet ceremony, married Betty Warren, an attractive divorce.

Ford spent the next 25 years in the House, maintaining his seat through careful attention to his constituents back home and rising in rank through seniority and his amiable relations with colleagues in both parties. He became known as an "Eisenhower Republican," advocating strong U.S. involvement abroad and governmental fiscal prudence at home. After the Democrats' landslide victory in 1964, Ford was elected House minority leader. "It wasn't as though everybody was wildly enthusiastic about Jerry," explained Representative Charles Goodell of New York. "It was just that most Republicans liked and respected him. He didn't have enemies."

And he didn't make any, even while trying to put the brakes on Lyndon Johnson's Great Society legislation, although L.B.J. mocked him gently by saying he had evidently played football without a helmet. After Nixon's election in 1968, Ford had a President he could work with but not a G.O.P. majority in the House. When Nixon's 1972 trouncing of George McGovern still failed to overturn the Democrats' congressional advantage, Ford began to consider retiring, feeling he would never become Speaker of the House. When Nixon's surprise offer of the vice presidency arrived, Ford told a colleague, "It would be a good way to round out my career."

Despite the public relief that greeted Ford's swearing-in, doubts about his fitness for the immense job he had been handed quickly began to spread. The fact that he would not have seemed out of place chairing a local Rotary Club meeting was, to many, a mark in his favor, another triumph of America's common man. But the nation in 1974 faced a number of complex and seemingly intractable problems. The cold war had grown even chillier after the Soviet support of the abortive October 1973 Arab attack on Israel. Then there were the agonizingly slow withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam, high inflation coupled with rising unemployment, and the aftershocks of the OPEC-engineered oil crisis of 1973. Given all that, just how common did Americans want their President to be?

Less than a month after taking office, Ford took a step that many believe doomed his presidency. His full pardon of Nixon for any crimes he may have committed while in office provoked a firestorm of criticism and outrage and led to widespread suspicion that Ford had made a secret quid pro quo — Nixon would resign if promised a pardon — with his predecessor. Congressional hearings were called, and Ford willingly appeared in person to answer questions. He denied making any deal with Nixon. The matter has been investigated many times since, and no evidence has ever been found to challenge the truthfulness of what Ford gave as his reason for the pardon. He believed that a protracted trial of Nixon would provide a rancorous distraction from the nation's pressing business and that his pardon was made for "the greatest good of all the people of the United States."

Ironically, doing what he believed to be the right thing deprived Ford of much of the public trust he had enjoyed on assuming the presidency. His approval rating, according to the Gallup Poll, plummeted from 71% to 49%. And those who did not think of him as untrustworthy began to see him as a bumbler.

For an accomplished ex-athlete, Ford sometimes displayed surprising physical awkwardness. He tripped, in full view of cameras, while descending the stairs from an airplane. During a charity golf event, the President's wildly errant tee shot conked a spectator. Such slips wouldn't have mattered a few years earlier, before the ubiquity of TV. Unfortunately for Ford, NBC had launched an experimental live-action comedy show called Saturday Night Live, designed to attract an audience of irreverent younger viewers. Chevy Chase, one of the original cast members, began playing Ford in skits and taking elaborate, deadpan tumbles, leaving the props and set in shambles. Viewers howled.

Ford took those gibes in good humor, another sign of his essential decency; he was not a collector of grievances like his predecessor. But the public perception of his occasional ineptitudes did not help him govern, nor did the heavy Democratic majorities in Congress after the 1974, post-Watergate elections. Ford remained committed to the broad designs of Nixon's foreign policy; one of his first acts in office was to ask Henry Kissinger to stay on as Secretary of State. Two important U.S.-Soviet agreements occurred during the Ford Administration: the Vladivostok Accords of November 1974, which built on the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty of 1972 and eventually led to SALT II, ratified in 1979; and the Helsinki Agreements of 1975, in which Western nations and the U.S.S.R. essentially recognized the existing political balances in Europe.

Ford's pursuit of the Nixon-Kissinger policy of dtente drew criticism from the Republican right, particularly from California Governor Ronald Reagan, who argued that that approach to the U.S.S.R. conceded its continued existence. It was another irony of Ford's tenure that his lifelong conservative credentials came to be challenged by his allies.

The one person who helped maintain Ford's common touch amid his political tribulations was his wife, Betty. She brought candor and originality to the White House, a freshness not seen since Jacqueline Kennedy. She kept the Executive Mansion real. "I took all the art off the walls — there's enough around — and put up family pictures," she told TIME in 1974. "I brought in Jerry's old blue leather lounge chair and his tobacco things." Until her husband succeeded to the presidency, the Fords had never lived in a house larger than eight rooms. Betty took delight in the incongruity of a messy family living in a 132-room mansion. "I looked around [a hectic clan dinner] and chuckled to myself. I thought, Well, it's the same old family table; it's just in a different place." Her daughter Susan, 17, was there with a nightcap over her curlers; her date was there in his dress pants and suspenders. The First Lady was in her robe. "It was just like home. I don't know what the staff must have thought." Betty's bout with breast cancer (and, after leaving the White House, her battle with drug dependency, which led to the foundation of the Betty Ford Center) further endeared her to the public. The fact that she adored her husband — and that he returned the love — made them touchstones of the commonplace by a populace tired of larger-than-life superpoliticos.

Outside the home, however, Ford's domestic record was spotty, largely because of the standoff between the White House and Congress. He had originally announced he would not run for President in 1976, but his sense of work left undone made him change his mind. Although Reagan won some Republican primaries, Ford arrived at the G.O.P. convention in Kansas City assured of the nomination. His Democratic opponent, former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter, ran energetically against Washington and the eight previous years of Republicans in the White House. Ford's aides at first planned to conduct a so-called Rose Garden campaign, capitalizing on their candidate's incumbency. When polls showed that strategy wasn't working, Ford hit the hustings hard.

The campaign's most memorable moment was, again unfortunately, an apparent Ford gaffe. During the second televised debate between the candidates, in San Francisco, the President said, in response to a question, "There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and there never will be under a Ford Administration." The tortured explanation for this statement emerged slowly over the next few days. Ford had not meant to deny Soviet military domination; he was simply unwilling to concede, probably as a sop to his party's right wing, that political domination was and would be a fact of Eastern European life.

The election was surprisingly close. Carter won, with 297 electoral votes to Ford's 241. The President, who had campaigned ferociously in the final days, was hoarse and teary when the results were announced.

Out of office, Ford continued to speak and tour energetically on behalf of his party. He toyed with the idea of running again in 1980, but even his close aides showed little enthusiasm. As the G.O.P. nominee, Reagan considered naming Ford his running mate. But Betty Ford had by then courageously made known her problems with drugs and alcohol, and former CIA director George Bush got the place on the ticket.

Living in Palm Springs, Calif., where the Betty Ford Clinic for addiction rehabilitation is located, the ex-President filled his private life with golf and lucrative board memberships (Shearson/American Express, the Beneficial Corporation of New Jersey, 20th Century Fox). He also shared a number of investments with millionaire Leonard Firestone. In 1996 BusinessWeek said Ford's personal fortune stood at roughly $300 million.

If Ford had been a different sort of public figure, the profits he reaped from his ex-presidency would have provoked an outcry. But the public had never perceived him as devious or venal; he was still, to a degree unique in recent presidential history, one of the people.