It's hard enough for kids to remember all the known oceans and seas — Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Norwegian, Barents — and now they can add one more to the list: the Enceladan Ocean. The name is lovely, and the place is nifty, but there's not much chance of visiting it soon. It's located on Enceladus, one of Saturn's 66 known moons. While Enceladus has been familiar to us since it was first spotted in 1789, the discovery of its ocean, courtesy of the venerable Cassini spacecraft, is a whole new and possibly game-changing thing.

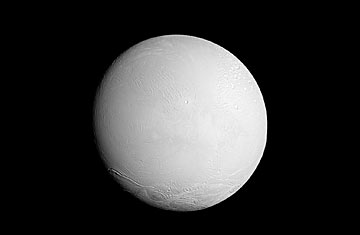

Enceladus has always been thought of as one of the more remarkable members of Saturn's marble bag of satellites. For one thing, it's dazzlingly bright. The percentage of sunlight that a body in the solar system reflects back is known as its albedo, and it's determined mostly by the color of the body's ground cover. For all the silvery brilliance of a full moon on a cloudless night, the albedo of our own drab satellite is a muddy 12%, owing mostly to the gray dust that covers it. The albedo of Enceladus, on the other hand, approaches a mirror-like 100%.

Life In the Universe: Easy or Hard?

Such a high percentage likely means the surface is covered with ice crystals — and, what's more, that those crystals get regularly replenished. Consider how grubby and gray a fresh snowfall becomes after just a couple of days of splashing road slush and tromping people. Now imagine how a moon would look after a few billion years of cosmic bombardment by incoming meteors.

When the Voyager probes barnstormed Enceladus in 1982, they found that the moon is indeed covered in ice and being constantly repaved. Vast valleys and basins were filled with fresh, white cosmic snow. Craters were cut clean in half, with one side remaining visible and the other covered over. Most remarkably, Enceladus orbits within Saturn's E ring — the widest of the planet's bands — and just behind the moon is a visible bulge in the ring, the result of the sparkly exhaust from ice volcanoes that trails Enceladus like smoke from a steamship. It's that cryovolcanism that's responsible for the regular repaving.

In 2008, Cassini confirmed that the cryovolcanic exhaust is ordinary water, filled with carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, potassium salts and other organic materials. Tidal pumping — or gravitational squeezing — by Saturn and the nearby sister moons Tethys and Dione keeps the interior of Enceladus warm, its water deposits liquid and the volcanoes erupting. The big question was always, How much water is there? A lake? A sea? A globe-girdling ocean? The more there is and the more it churns and circulates, the likelier it is that it could cook up some life.

The answer to that question finally came this week, thanks to Cassini images of stress cracks known as tiger stripes in the ice on the Enceladan surface. Cassini scientists were particularly interested in a pair of tiger stripes in the moon's warmer polar regions, since they are very deep and comparatively wide and seem to change over time.

The new images revealed that the cracks indeed widen and narrow and do so more than was once thought. The two sides of the cracks also move laterally relative to each other, the same way the two banks of the San Andreas Fault can slide forward and back and in opposite directions. And the greatest shifting, as expected, occurs after Enceladus makes its closest approach to Saturn.

"This new work gives scientists insight into the mechanics of these picturesque jets," says Terry Hurford, a Cassini associate at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. "[It] shows that Saturn really stresses Enceladus."

The fact that Enceladus becomes as dramatically distorted as it does is a powerful indicator of just how much water it contains. A watery world, after all, is a flexible world, and for Enceladus to be so elastic, it must contain a very large local ocean or perhaps even a globe-girdling one. Portions of that ocean may be not just bathwater warm but outright hot.

Enceladus is not the only moon in the solar system that is home to such a feature. Jupiter's Europa is even more certain to contain a global ocean of its own. On both worlds, organics plus water plus warmth plus time could be more than enough to get biology going.

"Cassini's seven-plus years ... have shown us how beautifully dynamic and unexpected the Saturn system is," says project scientist Linda Spilker at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The idea that that system might also be a living one has just become a little more plausible.